India’s Northwestern Region Likely To Confront Major Groundwater Shortage By 2025: Report

The report highlights the overexploitation of groundwater for agriculture, with 78 per cent of wells in Punjab considered overexploited

India’s northwestern region of India, particularly Punjab and Haryana are at risk of experiencing critically low groundwater availability by 2025, according to a report by the United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS).

The 2023 Interconnected Disaster Risks report focused on the issue of groundwater depletion in the northwestern region and underscored the critical concern that 70 per cent of groundwater withdrawals in the region are utilised for agricultural purposes.

Specifically, the report highlighted the alarming state of Punjab, where a staggering 98.9 percent of cropland relied on groundwater and surface water for irrigation. Within this context, a substantial 78 per cent of wells are deemed overexploited.

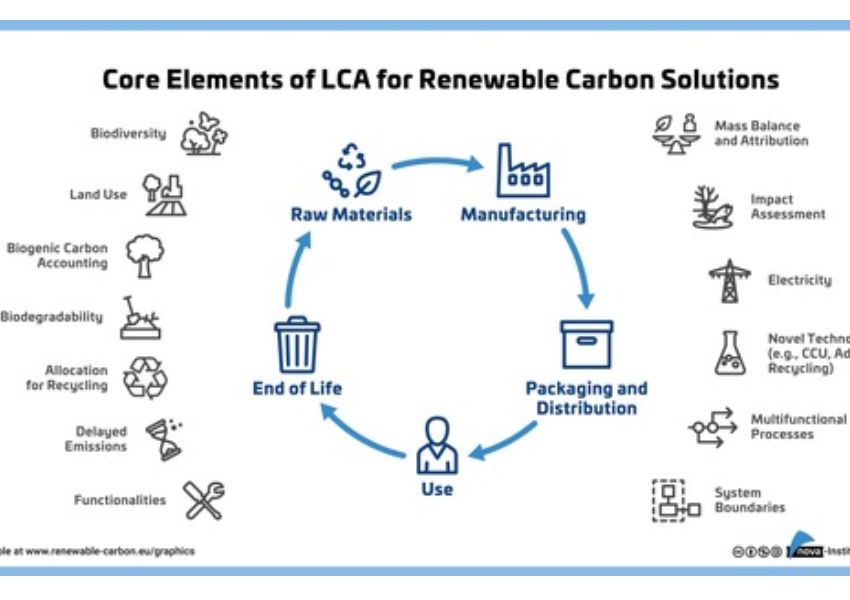

The report underscored the potential for irreversible damage to ecosystems and dire consequences for both people and the planet.

In addition to groundwater depletion, the report delved into five other key areas: accelerating extinctions, melting mountain glaciers, space debris, extreme heat, and uninsurable futures. The report clarified that the degradation of systems does not follow a straightforward and predictable path but rather evolves gradually until it reaches a tipping point, resulting in a fundamental transformation or even a collapse of the system, with potentially catastrophic repercussions.

A “risk tipping point,” as defined in the report, is the juncture at which a socio-ecological system can no longer absorb risks and fulfill its expected functions, leading to a significantly heightened risk of catastrophic impacts. These risk tipping points are not limited to single domains but are intricately interconnected and closely tied to human activities and livelihoods.

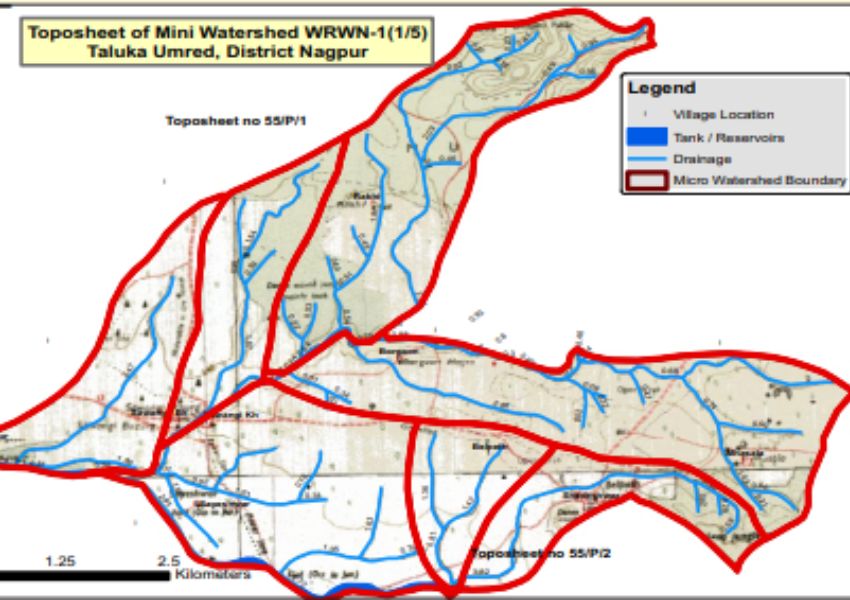

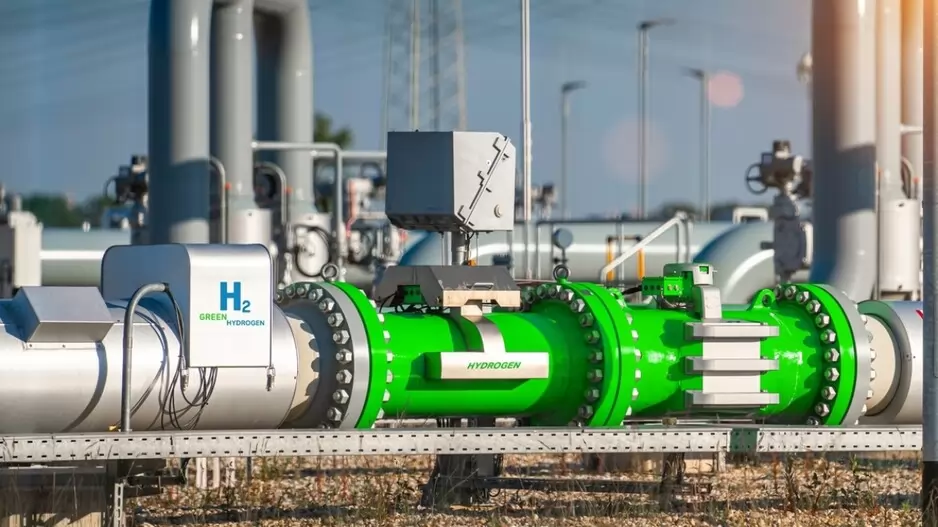

The report singled out agricultural intensification as a leading factor propelling the region toward a groundwater depletion risk tipping point. Groundwater irrigation currently supports approximately 40 per cent of global crop production, including staple crops like rice and wheat. The expansion of irrigated agricultural land has been made possible by access to groundwater, which has extended into semi-arid areas with limited precipitation and surface water.

Historically, food shortages and famine in India during the 1960s prompted a shift toward crop intensification. The government encouraged farmers to cultivate water-intensive crops such as rice, even in regions with inadequate climate and soil conditions. Punjab and Haryana have achieved remarkable productivity rates in wheat and rice, collectively contributing about half of the nation’s rice and wheat supplies. However, this excessive use of groundwater is pushing the north-western region as a whole to the brink of critically low groundwater availability in the near future.

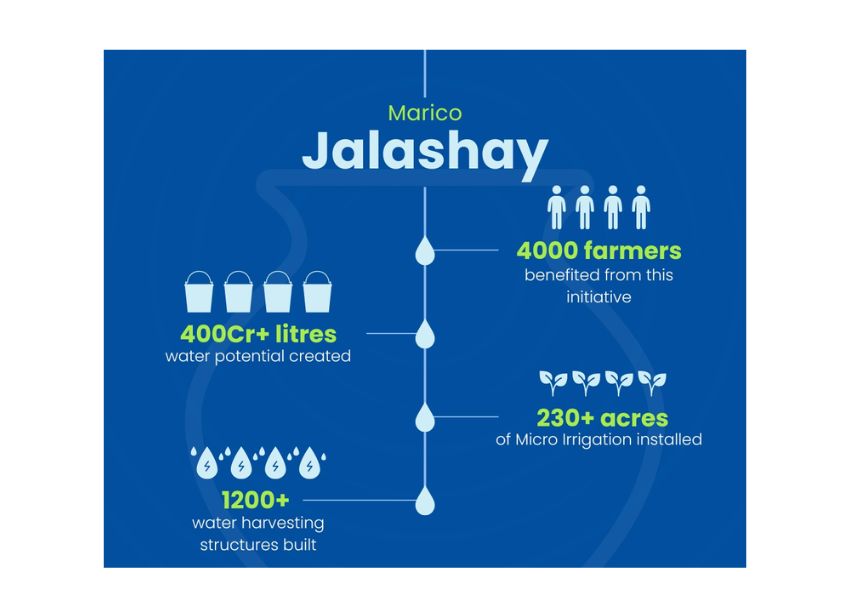

Groundwater is often seen as a dependable and stable water source, impervious to seasonal or climatic fluctuations. However, accessing groundwater is costly, involving expenses for well-digging equipment and electricity for pumping water to the surface. To ease the burden on farmers and make groundwater more accessible, some countries subsidise the energy costs of water pumping. While these subsidies are intended to enhance affordability and accessibility, they also elevate the risk of over-extracting this precious resource, disincentivising diversification of irrigation methods. Studies have shown that these energy subsidies contribute to groundwater depletion.

Following the earlier food shortages, a series of government incentives aimed at increasing the country’s food supply, including electricity subsidies for irrigation, have led to a surge in the number of wells across India since the 1960s. Increased access to groundwater has allowed farmers to intensify cropping and expand the number of cropping seasons each year, extending production into the predominantly dry winter and summer months.

However, difficulties in metering, billing, and collecting payments for electricity used in groundwater pumping prompted most State Electricity Boards to adopt flat tariffs in 1970, reducing the cost of pumping for farmers virtually to zero. While groundwater use and production have surged over the years, the development of alternative irrigation methods like canals has lagged behind.