Glo-cal Environmental Action Needs Local Indigenous Discourses

“The environment is viewed as an interdependent system where people, forests, and land are closely linked. Respecting the environment involves using its resources wisely to ensure sustainability and regeneration Glo-cal Environmental Action needs local Indigenous discourses,” writes Neeraja Kudrimoti, Associate Director at Transform Rural India.

“Amus and Beej Pandum” are very important festivals of the indigenous population in the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh, where they honour nature to seek blessings for a good harvest, fertile soil and favourable weather. The sowing of seeds is done ceremoniously, showing their deep respect for the soil and the environment. Indigenous communities, or Adivasis, living in forested, mountainous, and hilly areas, possess profound knowledge of their natural surroundings and rely on sustainable practices that harmonise with the environment. They play a vital role not only in preserving and sustaining but also in regenerating India’s biodiversity. However, their perspectives are often overlooked in global environmental discussions, which are dominated by complex scientific discourse. As they are the frontline interface for nurturing the environment, it is essential to induct their wisdom and practices into global environmental discourses to ensure comprehensive environmental action in a localised manner.

WHAT DOES CLIMATE & ENVIRONMENT MEAN TO THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES?

The environment for them encompasses the interconnected elements of water (jal), forest (jungle), and land (jameen) and is deeply embedded in their daily life. The environment is viewed as an interdependent system where people, forests, and land are closely linked. Respecting the environment involves using its resources wisely to ensure sustainability and regeneration. This relationship with the environment is essential for providing livelihood, nutrition, medicines, wisdom, and identity. Sukhri didi from Bijapur district shared her concerns about how land and nature play a vital role in her life and her community. The land and the forest are their lifeline. Their food, income, traditions, all are derived from the soil. The forest is their mother; it gives them food and medicine. The climate dictates their farming calendar and affects the forest, and in turn, their lives.

WHAT ARE THE PRACTICES THEY FOLLOW?

The indigenous people use festivals as opportunities to conserve the environment. Rituals for checking the water retention capacity of the soil to predict rainfall patterns, gifting seeds, and conducting plantation drives during festivals to preserve and disseminate traditional varieties are prevalent. The use of natural resources such as scattering neem and other bitter leaves around homes to protect against insects and pandemics and the use of Dhelwa, a wild medicinal herb, for deworming cattle, is common. Hareli festival in July for offering prayers to greenery, crops, and agricultural equipment, and Pola, which involves the worship of bulls and building mud houses are quite important. These practices reflect the community’s deep connection with their natural surroundings and commitment to sustainable living. The traditional education system of Ghotul that taught environment and science was also a unique feature. Many seasonal rhythms and sustainable practices are followed, such as collecting and using mahua flowers for nutritional and cultural purposes, producing mahua oil for cooking, which is crucial for sustenance. Relying on the sustainable harvest of Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFPs) and engaging in activities like collecting firewood and preparing traditional meals are very typical internalised routines for the communities. Some other practices such as annual cleaning and purification of local streams and rivers (Jal Suddhi), performing the “Baiga Chewer” ritual, where a portion of gathered products is left in the forest as an offering to ensure Water and Forest Conservation, are quite close to their hearts.

WHAT ARE THE SHIFTS IN NATURE THAT THEY EXPERIENCE AND MEASURE?

The most important shift that the communities emphasize is around water and rainfall, which drives biodiversity, productivity, and quality of life. But reduced and irregular rainfall patterns have led to wild animals searching for water in human habitats and altered behaviours in flora and fauna. Communities have also reported never-seen-before rivers drying up, soil hardening, new insects damaging plants, changes in bird migration patterns, and unprecedented tree deaths rather than just shedding leaves. This has changed agricultural patterns, with lower crop yields and disrupted growth cycles, shifting or reduced earthworm populations, reduced access to fodder from jungles leading to a decline in livestock rearing. NTFPs observe a decrease in availability due to climate fluctuations, untimely maturing/flowering, and hence, reduced income. The heatwaves this year have been especially bad. Women in these areas are not only the ones who undertake the laborious work of livelihood activities but also primary caregiving. An indigenous woman from Sukma district of Chhattisgarh shares her experience, “Summer this time has caused nausea, tiredness and lethargy never experienced before and the problem amplified since we have to travel a longer distance to fetch water”. The horticulture and poultry sectors in rural areas are severely affected due to high vegetable loss and reduced egg production. Another indigenous woman from Bastar quotes, “Last summer we were able to produce a vegetable or two for our own consumption, but this year has been brutal since not a single drop was left in the river to grow vegetables and our dependence on the already expensive and inaccessible market has multiplied”. Migration to cities due to dwindling resources is on the rise, and it demonstrates how climate change and modernization are affecting traditional lifestyles, agricultural practices, and environmental health.

WHAT ARE THE SOLUTIONS PROPOSED BY THEM?

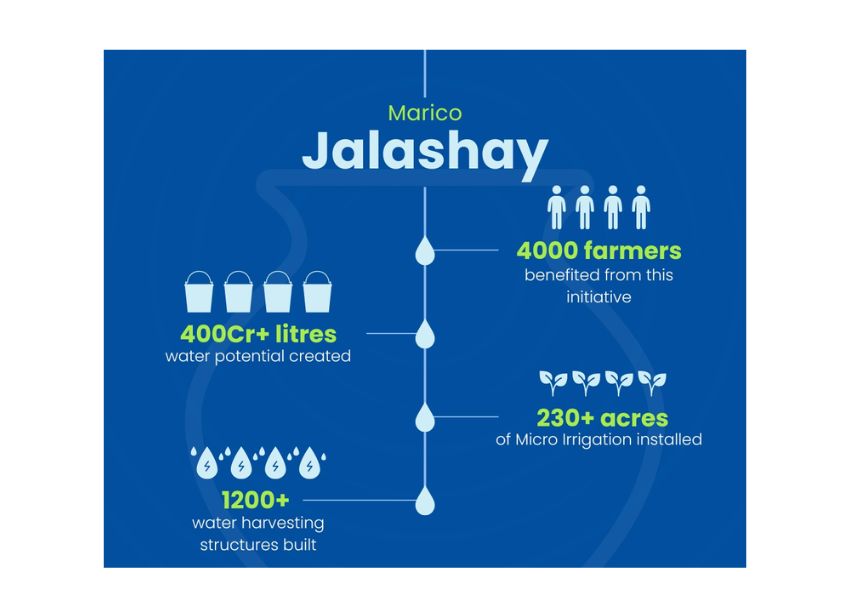

Interestingly, there are amazing solutions proposed by these communities; they know their solutions well, and they will and already are attempting to implement them in a localized contextualised manner. Improved Agricultural Practices are being taken up, such as encouraging organic farming to reduce reliance on chemical fertilisers and pesticides and adoption of traditional farming methods using cows and bulls to lessen pollution and protect nature from climate change. Communities also prescribe the importance of education and awareness about preserving natural resources, traditional knowledge, and biodiversity by integrating it with modern technology. As many of their festivals involve afforestation, forest management, and green initiatives, they also heavily aspire to water conservation, water-saving techniques, and water-friendly crops (such as millets). There was a need seen among them for better environmental governance as a backdrop to everything which should ensure community engagement and decision-making fostering collaboration between stakeholders. By implementing these solutions, the indigenous people aim to address the adverse effects of climate change, preserve their cultural heritage, and ensure sustainable development.

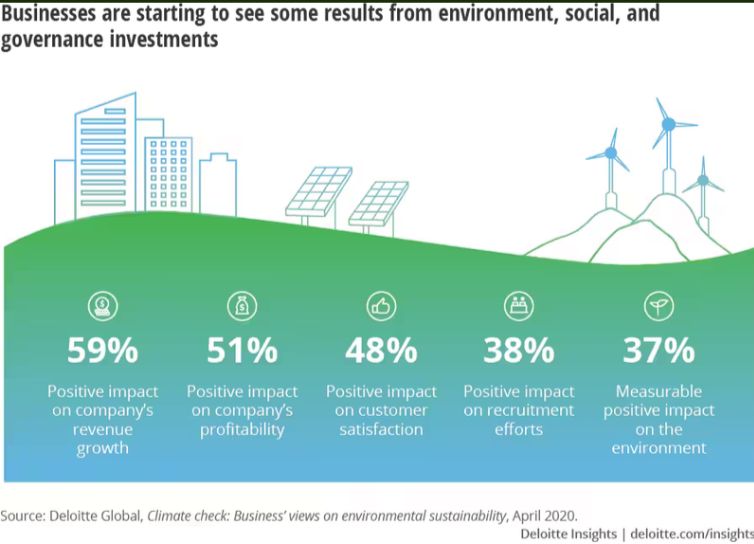

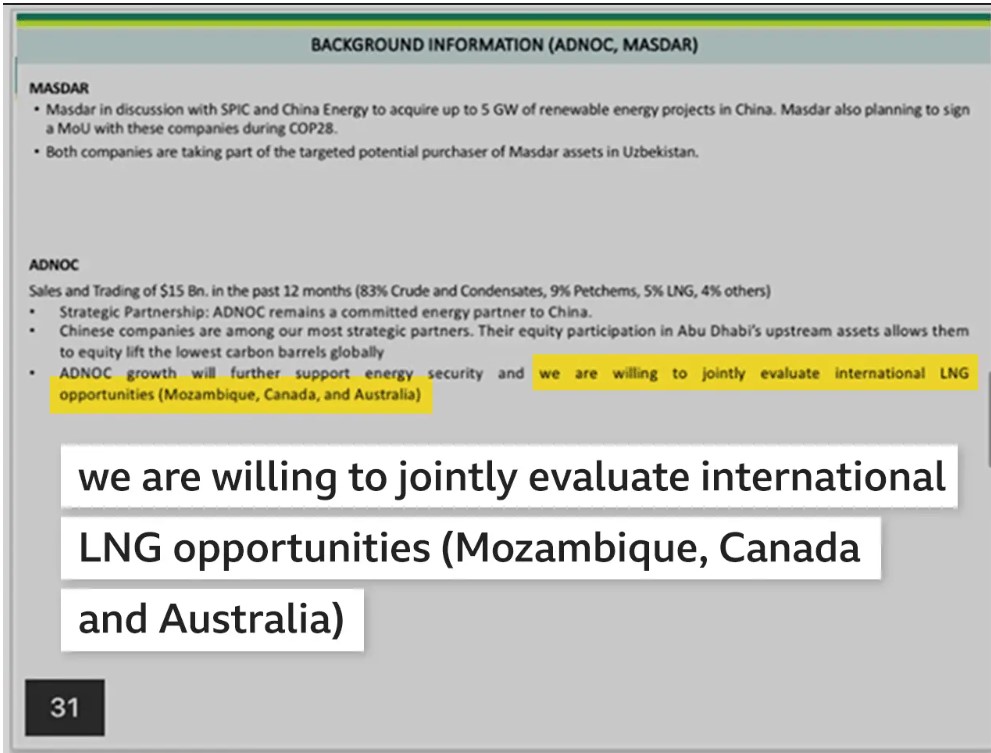

SYNERGIES WITH GLOBAL DISCOURSES

The current global environmental narrative has its own vocabulary such as climate change, emissions, socio-ecological systems, sustainability & ESG, renewables, pollution, restoration, conservation and so on. But the discourses are different from those of the indigenous communities. The shared way of comprehension and interpretation of the environmental issues, accounts & narratives that inform each other, converging the local and global discourse. A better design for interactive and collaborative frameworks for that to happen needs to evolve. For instance, the most recent COP28 did well on the increased representation from the indigenous peoples but did not do enough for their mode of participation as they were more of spectators. There is a need to ensure that environmental governance can better address the needs and rights of indigenous communities. Indigenous communities depend a lot on the government architecture and hence, the public system delivery architecture needs to be strengthened and a cohesion between communities, Panchayati Raj Institutions and frontline administration is key. We need to move from a sustainable to a more regenerative approach with continuously evolving knowledge management, research, and investment mechanism for dialogues on promotion and prescription of the traditional environmental practices are needed as well. In today’s glo-cal landscape of digitisation, socialisation, and privatisation.