Navigating Voluntary Carbon Markets: Promise, Perplexity, and Potential

“Climate change is a reality, and carbon emissions are the culprits.” The urgent need to limit our carbon footprint has given rise to an innovative mechanism – voluntary carbon markets. In the heart of this growing market, India is crafting its path with the introduction of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) 2023 by the Ministry of Power. This scheme signifies a bold step towards creating a domestic marketplace for tracking and trading carbon credits. Yet, this journey is not without its share of enigmatic prospects and uncharted challenges, making it a story of promise and puzzlement.

Voluntary Carbon Markets in India: The Prospects

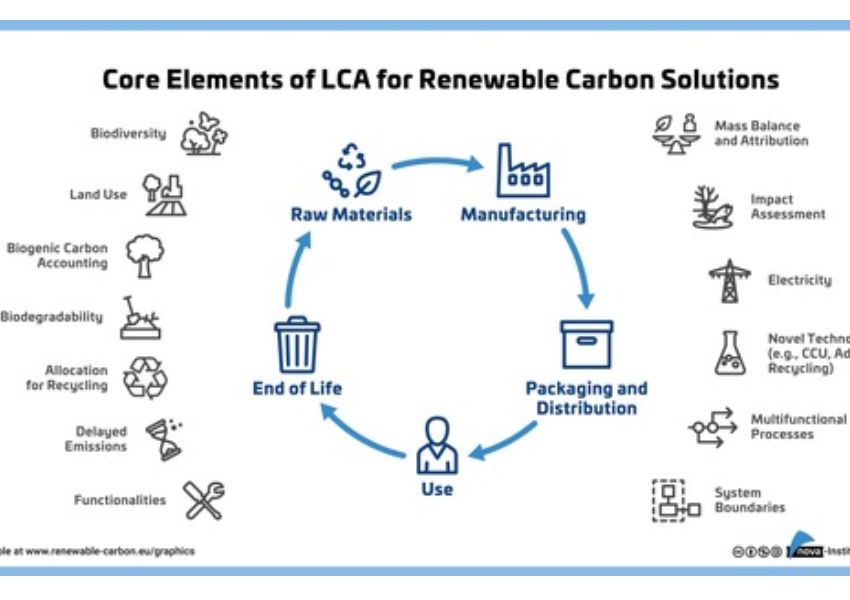

In the landscape of carbon markets, the voluntary carbon market (VCM) stands apart from its compliance counterparts due to its unique characteristics. Unlike compliance markets, where rules and standards are set by national or international public authorities, the voluntary carbon market operates in a realm governed by private entities. These private entities, often taking the form of non-governmental organizations, define the standards that determine project certification and carbon credit generation. Each standard brings its distinct eligibility criteria for projects and entities, creating a mosaic of regulations that participants must navigate.

To add to the complexity, the nomenclature for these carbon credits is as diverse as the standards themselves. Some call them carbon credits, while others prefer terms like Verified Carbon Units (VCUs) or Plan Vivo Certificates. This diversity contributes to the intricate web of carbon markets.

The absence of a centralized governance body implies difficulties in legally classifying voluntary carbon units. In the European Union, for instance, carbon allowances under the EU Emission Trading System are classified as financial instruments. In contrast, voluntary carbon credits remain unclassified, leaving each member state to determine its status as per its discretion.

However, this lack of governance also brings forth an intriguing prospect – the fluidity of the voluntary carbon market. Unlike compliance markets bound by stringent legislation, VCM offers participants the freedom to engage in carbon credit trading regardless of their geographical location or business sector. A private company based in Europe can invest in carbon credits that support rainforest preservation in South America, transcending borders, and sectors.

The only constraints within VCM originate from the standards themselves, which being private entities, remain subject to negotiation. This flexibility in standards presents a unique opportunity for market participants to shape the market’s future.

The Challenges

Amidst the promises of the voluntary carbon market lies the challenge of trust. The lack of standardized governance and unified criteria for carbon credit qualification means that the quality of a carbon credit can vary widely between standards. Participants often find it challenging to assess the environmental integrity of a given carbon credit, and this lack of transparency hinders the market’s credibility.

Further, one of the most intriguing challenges within the voluntary carbon market is the missing link to compliance markets. While both compliance and voluntary carbon credits are transferable rights used for emission reduction, the absence of an administrative component in the voluntary market differentiates it from compliance markets. Compliance markets like the EU Emission Trading System involve legally binding obligations for entities to retire allowances, which is absent in VCM.

Additionally, a significant challenge revolves around determining the primary buyers of Indian carbon credits. The question arises whether Indian corporate entities will be the primary purchasers, or if the market will attract a global audience. Similarly, the preference for Indian credits over established standards like VERRA and Gold Standard (GS) needs exploration, considering factors such as pricing, project types, and the perceived environmental impact. Clarifying the target market and understanding the competitive advantages that might make Indian credits preferable, therefore, will be crucial for the success of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) in India.

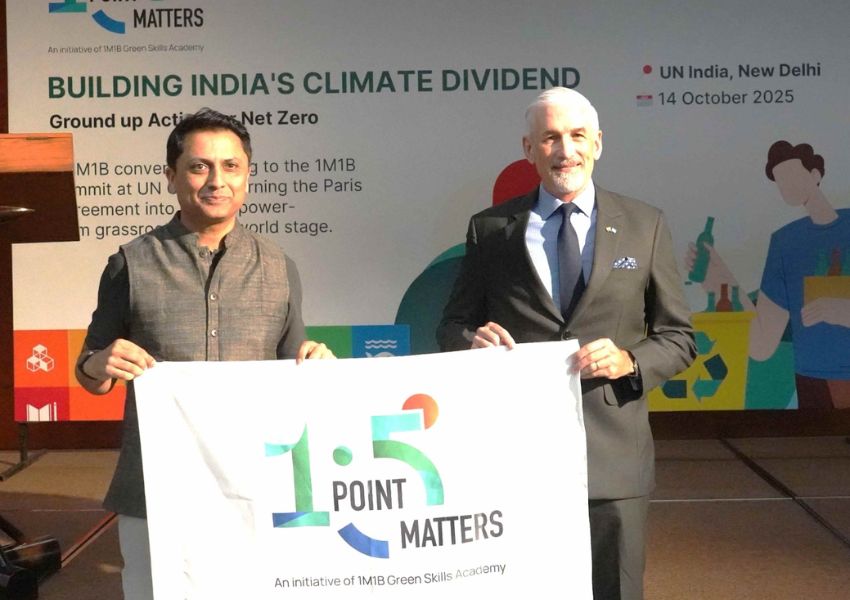

However, the Paris Agreement’s Article 6, designed to promote international cooperation for carbon emission reductions, holds the potential to bridge the gap between compliance and voluntary markets. Whether VCM can be integrated into compliance mechanisms such as the EU ETS or the European Commission’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism remains uncertain and awaits regulatory decisions.

Indian Context

In the Indian context, the Ministry of Power’s Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) 2023 is a significant step forward in creating a domestic market for tracking and trading carbon credits. This scheme builds on existing mechanisms like the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) for tradable energy certificates and the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) for renewable energy certificates. CCTS transitions from using tonnes of oil equivalent (ESCerts) to carbon certificates expressed in tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent.

The notification for CCTS outlines the framework and structure of the domestic carbon market, including establishing a National Steering Committee. This committee will provide recommendations to the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) for setting emissions targets and trajectories for obligated entities. The BEE will play a central role in accrediting carbon verification agencies, and the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) will regulate certificate trading.

The Unanswered Questions

The introduction of the Carbon Market under the CCTS is a significant development, yet numerous critical questions and challenges demand clarification. First, there’s a lack of clarity regarding the operationalization timeline, leaving stakeholders eager to know when and how different market segments will function. Second, the eligibility criteria for sectors and industries in the domestic carbon market remain unspecified, a crucial consideration given potential sector expansion. Uncertainty also surrounds the relationship between global and domestic carbon credit certificates, impacting India’s foreign investment prospects for decarbonization. Ensuring accurate price discovery for carbon credits, especially in the voluntary market, is crucial for market effectiveness. Furthermore, the governance structure of the Indian voluntary carbon market requires clarification, including the role of industry stakeholders. Lastly, the interaction between the CCTS and initiatives like the Green Credit Programme needs clarification, particularly concerning potential overlaps and interactions between green and carbon credits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as India takes its first steps towards establishing a robust domestic carbon market, the journey is marked by both promise and perplexity. While the prospects for voluntary carbon markets in India hold great potential, the challenges and unanswered questions underscore the need for clear and comprehensive regulations, governance structures, and market mechanisms. As the nation commits to combating climate change and creating a transparent and efficient voluntary carbon market, the story continues to unfold with each step taken towards a sustainable future.