Nations Reject Weak Carbon Market Rules

Countries have failed to adopt rules under Article 6.2, which covers bilateral actions between countries to reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions

Nations failed to reach a consensus on regulations to create a global carbon market during the 28 Conference of Parties (COP28) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which concluded on December 13. The fact that the signatories to the Paris Agreement did not adopt lax regulations for carbon markets that would have jeopardised the rights of Indigenous Peoples, human rights and the integrity of ecosystems has been applauded by civil society organisations.

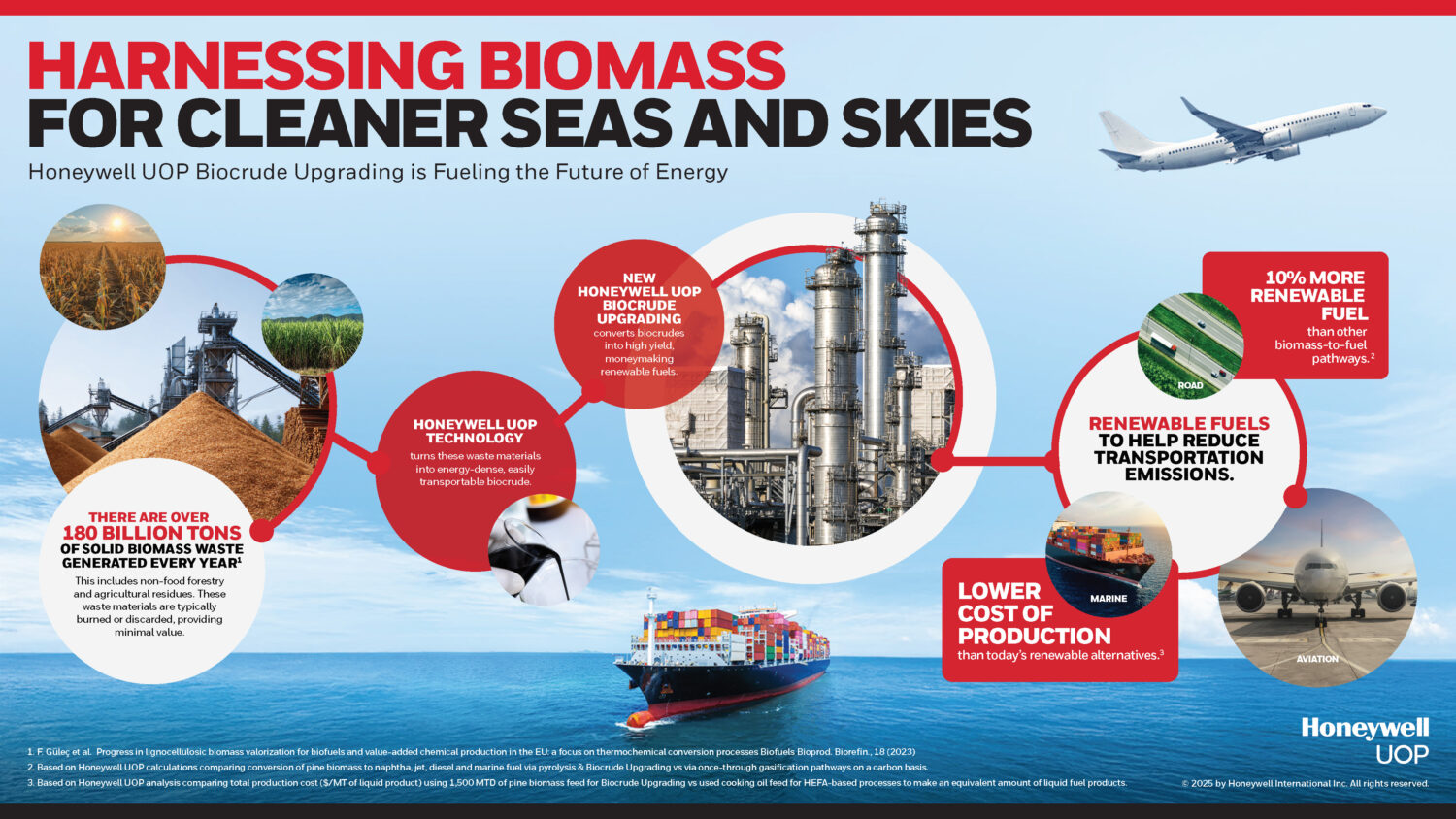

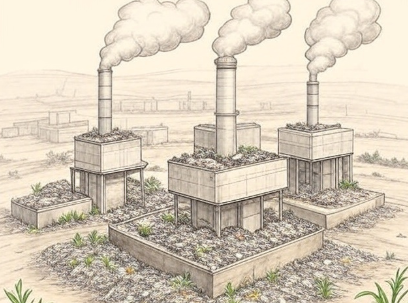

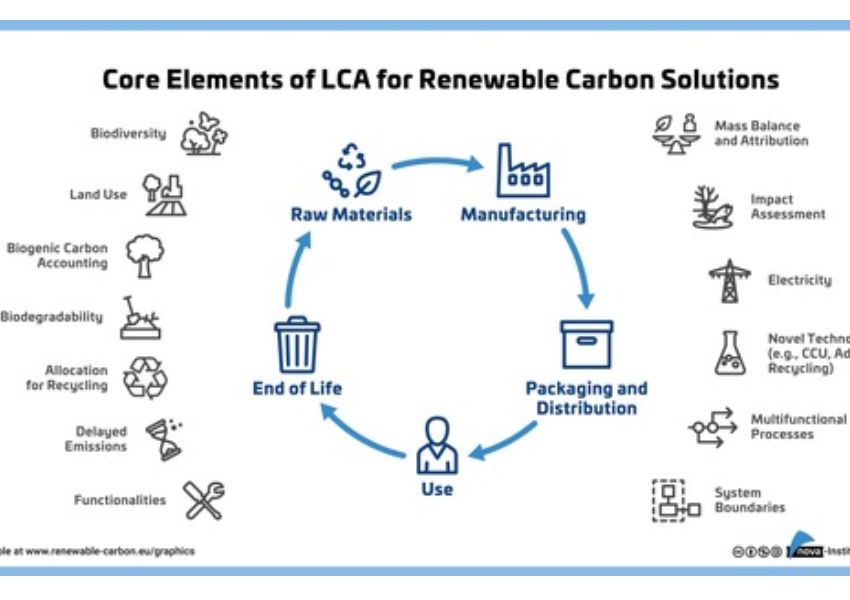

In accordance with Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, which permits the trading of carbon credits produced by lowering or eliminating greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere, nations negotiated regulations to establish the global carbon market at COP28. Carbon removal projects could be nature-based, which uses forests, mangroves and agricultural soil to capture and store carbon, or technology-based solutions, such as deploying big machines to capture and store carbon dioxide.

A proposal for an emission reduction or removal project developed under section 6.4 must be submitted to the Supervisory Body, a body responsible for managing the market. Upon approval, these projects have the potential to yield carbon credits equal to one metric tonne of carbon dioxide. To meet their climate targets, nations, businesses and even individuals can acquire these credits.

On 12 December, the conference unveiled a draft negotiating document that included suggestions for standardising methodology and getting rid of techniques used to figure out project-level emission reductions. Nevertheless, nations were unable to agree in a summit that followed the distribution of the text.

The European Union (EU) voiced its concerns about the draft text the day before, December 11, saying that it needed to show that carbon markets could make a difference and aid in closing the gap that exists. The EU negotiator feels that the current text does not provide a strong enough message.

The EU stated that the removal guidelines are not yet ready for application, even though they recognised that the criteria on methodology are clear, ambitious and suitable for their intended use.

The significance of robust environmental and human rights laws in carbon credit trading was underscored by Gilles Dufrasne, the Policy Lead for global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch. The recent controversies surrounding the voluntary carbon market, he claimed, had brought this to light.

He believed that the language on the table did not offer these protections and that passing it would have resulted in a recurrence of the mistakes that the voluntary carbon markets had made. As a result, by rejecting it, the negotiators made the proper choice.

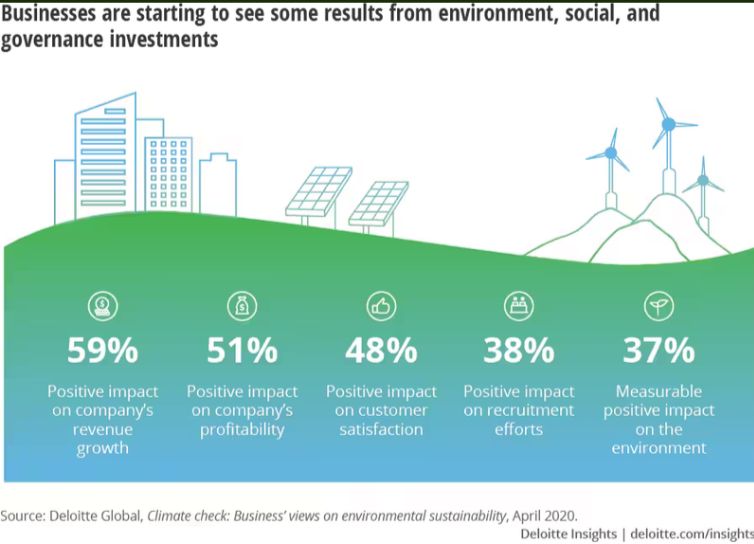

To reach net-zero emissions, companies use voluntary carbon markets to offset remaining or inevitable emissions. However, a study conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment and Down To Earth (DTE) revealed that these kinds of markets could not be good for the environment or the public.

Over the next year, the supervisory body will be responsible for developing several tools necessary for carbon credit trading, including a risk assessment tool for reversals of removals, an additionality tool and creating a registry to track, manage and trade greenhouse gas emissions. Jonathan Crook, a policy expert on global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch, stated that projects under 6.4 are not expected to be operational until 2025.

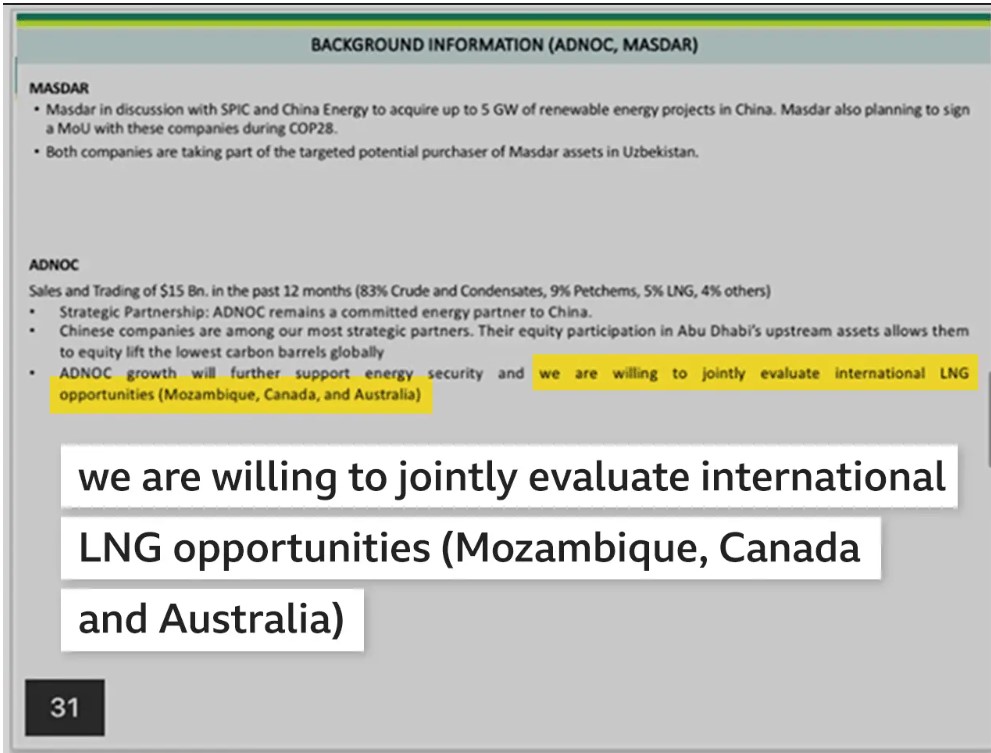

Additionally, countries have failed to adopt rules under Article 6.2, which covers bilateral actions between countries to reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions. However, countries such as Switzerland, Japan, Singapore and others have already started inking deals.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme Copenhagen Climate Centre, a total of 139 pilot projects have been recorded, of which 116 belong to Japan´s Joint Crediting Mechanism, a Japan-initiated bilateral mechanism for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

With rules in place, countries could avoid issues like double-counting, where the host and the buyer count greenhouse gas emission reductions. Jonathan Crook warned against the minimalist and no-frills framework that was on the table, which would have allowed countries to broadly define their reporting rules and trade carbon credits flagged as flawed. Also, governments could revoke authorisation for previously approved carbon credits without any limits, which could have led to double-counting.