The Billion-dollar Cost Of Water Mismanagement In India

Mismanagement of water resources is draining India’s cities, costing billions annually and threatening their future sustainability

Byline: Vikas Brahmavar, Co-founder, Boson Whitewater

Water seems abundant until it isn’t. Indian cities know this far too well. Despite seasonal downpours and access to major rivers, urban India keeps sliding deeper into water stress. One of the starkest examples is Bengaluru, a city where it’s common to see both overflowing storm drains and dry borewells in the same week.

Behind the chaos is a simple but uncomfortable truth: our cities aren’t short on water, they’re short on management.

Bengaluru gets a significant portion of its water, around 1,460 million litre per day (MLD) from the Cauvery River. That water doesn’t just flow into the city; it’s pumped from a reservoir nearly 90 km away and 300 metre below the city’s altitude. The cost of this? Roughly Rs 3 crore per day in electricity bills, just to get the water here. That’s over Rs 1,000 crore a year, spent just on power to transport water.

And that’s not the only expense. What the city can’t supply through pipelines, residents source by drilling deep borewells, often 1,000 feet or more. These also need power to operate. It’s estimated that around Rs 2.7 crore is spent daily on pumping up groundwater. Between river water and groundwater, we’re already looking at nearly Rs 6 crore per day, close to Rs 2,200 crore annually, and this doesn’t even include what people pay for private tankers.

Leaks and Losses

Not all of this water reaches homes and taps. A chunk of it, around 30 per cent of piped water, is lost before it even gets there. Some of this is due to leakages in ageing infrastructure, and the rest from unauthorised connections or poor metering.

In real terms, about 448 MLD of water is lost daily. Out of that, around 331 MLD is actual leakage, water escaping through cracks and breaks in pipes. Even if some of this seeps into the ground and recharges aquifers, it’s still a highly inefficient and expensive way to manage water. If you assign a value of Rs 30 per kilolitre, a conservative estimate, this leakage costs the city nearly Rs 10 crore every day. That’s over Rs 3,500 crore annually gone, literally, down the drain.

Wastewater: A Missed Opportunity

If the supply side looks inefficient, the waste side isn’t much better. Bengaluru generates nearly 1,940 MLD of wastewater every day. But only 63 per cent of it is treated by the city’s large sewage treatment plants. Another 13 per cent is handled by smaller, decentralised plants. That leaves nearly a quarter of the city’s wastewater untreated, flowing directly into lakes or the ground.

Even where water is treated, it’s rarely reused. Only about 30 per cent of treated water is repurposed for uses like gardening, construction, or industrial cooling. The rest is simply sent out of the city, often to the rural outskirts for irrigation. That water, moved with no associated revenue or cost recovery, represents waste of money and infrastructure.

Apartments are Spending, But Getting Little in Return

Let’s zoom into the city’s residential pockets, and you’ll see the same story repeated. Around 3,500 apartment complexes across Bengaluru have their own small STPs (sewage treatment plants). These are mandatory by law and cost, on average, Rs 1.5 lakh a month to operate.

But here’s the problem: only about 20 per cent of the treated water is reused, mostly for gardening. The rest? Flushed away. That means for every Rs 1.5 lakh spent, Rs 1.2 lakh effectively disappears. Multiply that across all complexes, and you’re staring at a loss of over Rs 500 crore a year, just in wasted potential.

Environmental Cost

The financial side is just one part of the story. The environmental cost of all this, the carbon footprint from pumping, transporting, and wasting water, is massive. Every drop pulled from a borewell or moved via tanker carries with it a load of emissions. With climate change already reshaping rainfall patterns and intensifying droughts, this kind of system isn’t just inefficient, it’s dangerous.

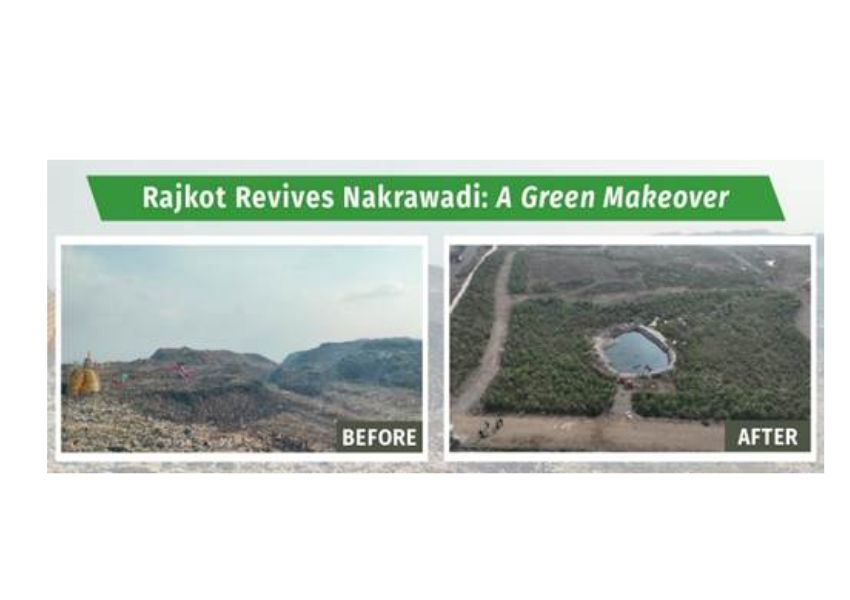

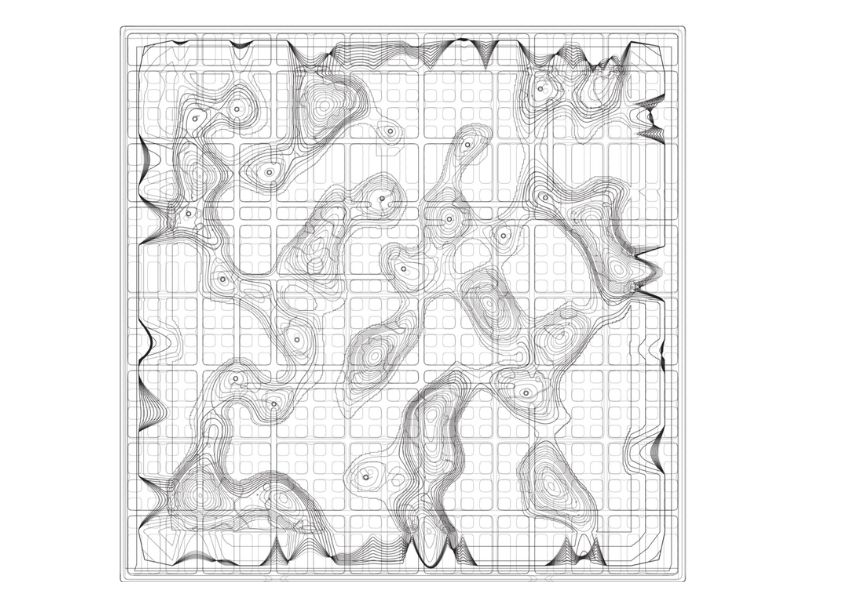

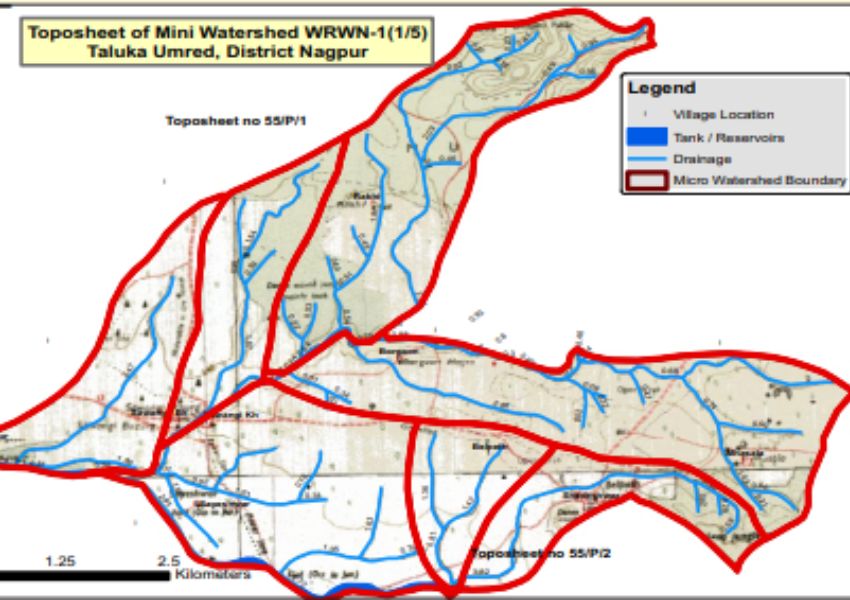

This isn’t a new problem, and experts have been pushing for solutions for years. But what’s clear now is that piecemeal efforts— a few rainwater harvesting systems here, a decentralised plant there—won’t cut it. Bengaluru, and cities like it, need a circular water economy.

That means capturing and reusing wastewater on a wide scale. It means making rainwater harvesting the norm, not the exception. It means fixing leakages fast and building systems that let water do more than one job before it’s let go.

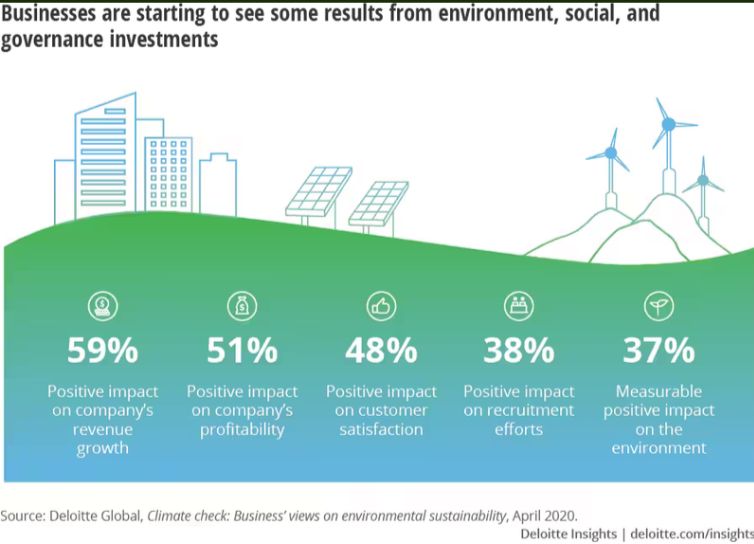

This isn’t just Bengaluru’s headache. Delhi, Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune—every major Indian city is dealing with versions of the same issue. As urban populations swell, the stress on water systems will only grow. The World Bank has warned that water mismanagement could cost India 6 per cent of its GDP in the coming decades.

That number might seem abstract, but the symptoms are all around: tanker queues, summer water fights, rising utility bills, and disappearing lakes. The billion-dollar cost isn’t coming, it’s already here.

Conclusion

We often think of water as free, something that should always be available. But in reality, every litre that flows to our homes comes at a cost. Energy, infrastructure, maintenance, and, if mismanaged, huge financial loss. Bengaluru’s experience shows that mismanaging water doesn’t just lead to scarcity. It leads to spiraling costs, wasted investments, and eventually, a crisis of trust in the system.

It’s time to treat water for what it truly is: a valuable, finite, and highly misused resource. If we don’t, we’ll keep paying the price, and not just in money.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.