India’s Upcycled Fashion Faces Scale, Policy Hurdles

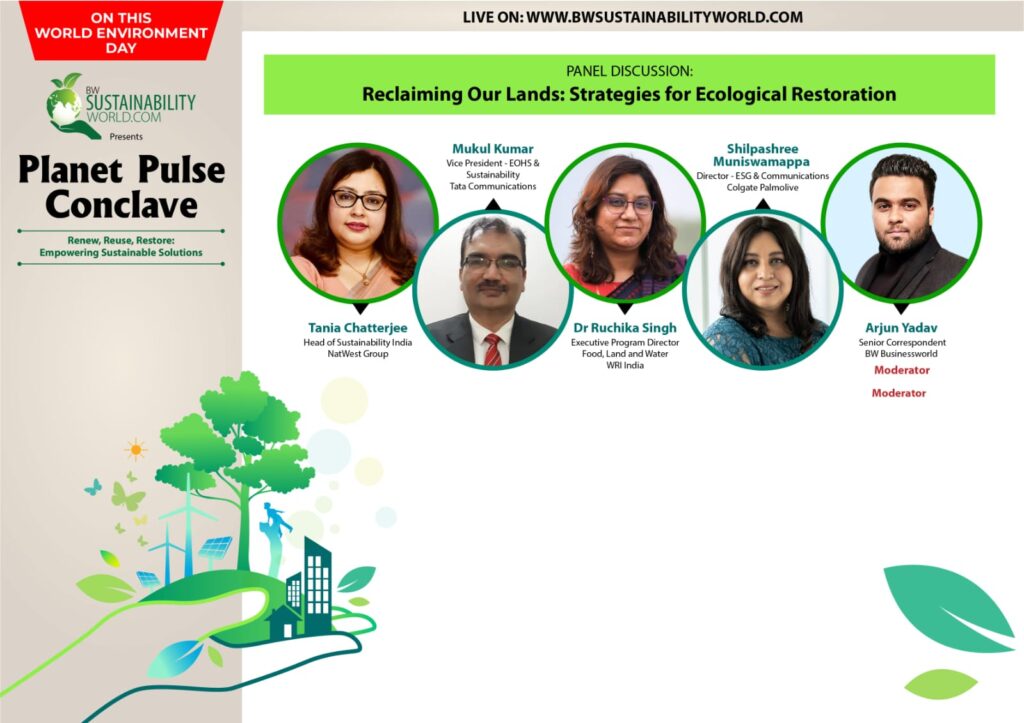

As international markets demand traceability, India’s domestic ecosystem still lacks support for true textile circularity

Byline: Kashish Saxena

Delhi-based fashion label Doodlage is betting on international expansion as a way to scale its upcycled business model while retaining tight control over inventory and production waste. Founded over a decade ago by designer Kriti Tula, the company works primarily with post-production fabric waste to create small-batch collections.

When asked about the rationale behind the global push, Tula said the brand is focusing on creating event-based, low-inventory experiences in new markets. “Instead of mass-stocking, our model focuses on sample-based collections and on-demand production to limit excess inventory,” she noted.

The brand has already identified local partners in Switzerland, the UAE, the US, and Australia to facilitate its entry into those regions. According to Tula, Doodlage’s ability to replicate styles from textile waste, something many upcycling brands struggle with, is a key differentiator. “We have spent years building a direct supply chain with traders and export houses, allowing us to consistently access raw material and maintain replicability,” she said.

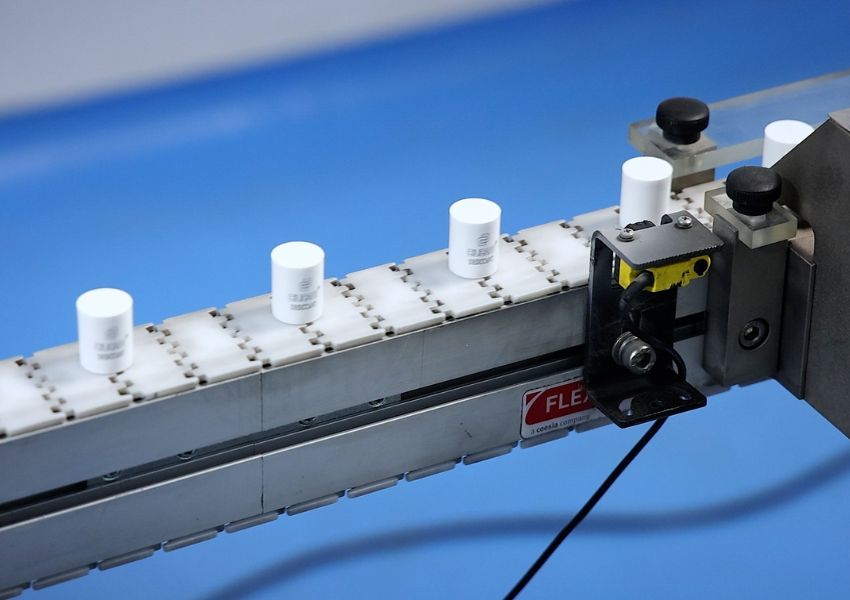

India’s textile and apparel sector, one of the largest globally, generates significant quantities of post-production and post-consumer waste. While this creates an opportunity for upcycled fashion, the ecosystem remains underdeveloped. Supply chain fragmentation, inconsistent quality of waste material, and a lack of formalised textile recovery systems continue to be key operational barriers for brands working with discarded fabrics.

Policy Gaps, Cost Structures

When asked about policy challenges, Tula pointed to the lack of implementation around Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) in India’s textile sector. “Circularity is widely acknowledged in principle, but producers are not yet being held accountable for waste generated after the point of sale,” she said.

Tula argues that the design phase of garment production is crucial for enabling future recyclability, something many large brands overlook. Blended and synthetic fabrics, she said, are still the industry standard and remain hard to recycle.

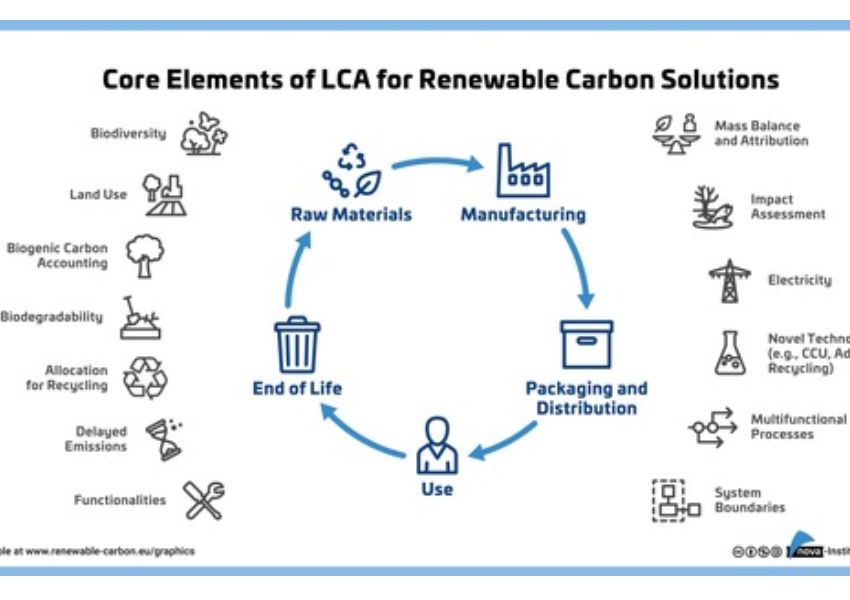

While international markets are starting to push compliance, frameworks related to traceability and lifecycle reporting, India’s domestic fashion landscape is still largely unregulated in this regard. Even brands that intend to work sustainably face high friction in setting up ethical sourcing networks, reverse logistics systems, and traceable waste streams, often without government or industry support.

The conversation also touched on the cost of sustainable fashion, a subject that often surfaces when comparing prices with mass-market apparel. According to Tula, higher pricing is inevitable due to the structure of sustainable supply chains. “Even if we scale, we’re not going to match the Rs 150 T-shirt,” she said. “We produce in smaller volumes, pay fair wages, and build custom supply chains—there’s a cost to all of it.”

Consumer Shifts

Tula addressed that high prices limit mass-market adoption but stated that alternatives exist. “If consumers can’t afford new sustainable clothing, they can still thrift, swap, or repair what they already own,” she said.

She added that while awareness around sustainability has increased, widespread behavioural change remains slow. “There’s more information today than a decade ago, but slowing down consumption still hasn’t become mainstream,” she said when asked if society itself is a barrier to circularity.

In the absence of systemic infrastructure, much of the burden for sustainable consumption has fallen on consumers and independent brands. Tula noted that without accessible, affordable alternatives and a culture of clothing repair or exchange, large-scale behavioural shifts are unlikely to take root.

Business Model

Doodlage primarily operates as a direct-to-consumer (D2C) brand via its own website and select pop-up events. It avoids trend-driven seasonal cycles by reusing successful silhouettes across different materials. “If something is working, we’ll continue offering it in new fabric options rather than developing entirely new collections,” Tula said.

On the B2B front, the brand is also supplying recycled materials for corporate packaging, uniforms, and gifting. According to Tula, expanding the supply chain’s utility beyond fashion helps improve resource efficiency and revenue diversification.

The brand currently works with a 20 per cent profit margin. Tula noted that although this limits the pace of scaling, it keeps the brand aligned with its core values in the absence of patient capital. “India has the manufacturing advantage, but capital support for sustainability-focused brands remains limited,” she said.

Looking ahead, Doodlage’s global strategy involves controlled exposure through curated collaborations, experience-based retail, and low-waste distribution. “Even for international stores, we prefer they hold sample sets and take orders, rather than overstocking inventory,” Tula explained.

Sustainable fashion in India is still finding its footing. High price sensitivity and patchy infrastructure have made it a tough space to scale. But brands like Doodlage are quietly choosing to grow in a way that is mindful of both resources and impact. As global supply chains begin shifting from talk to action on sustainability, what will set brands apart is their ability to match good intentions with workable, real-world systems.