How Indonesia & India Can Lead The Way In Sustainable Palm Oil Production

According to the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (INDEF), around 40 per cent of Indonesia’s palm oil is cultivated by smallholders who are deeply embedded in the future of the industry

Byline: Eddy Martono, Chairman Of Indonesian Palm Oil Association

I often find myself gazing at the long rows of palm stretching across Sumatra and Kalimantan, not with the satisfaction of scale, but with a more intimate question: What will these trees mean to the next generation? Will they be seen as emblems of short-term extraction or as monuments to a deeper, collective intelligence, one that reconciles productivity with planetary boundaries? The answer lies in what Indonesia and India decide to do next. Not separately, not competitively, but together. The future of palm oil will not be shaped by technology alone, or by Western standards, but by a new kind of South-South leadership; one that we must now be bold enough to define.

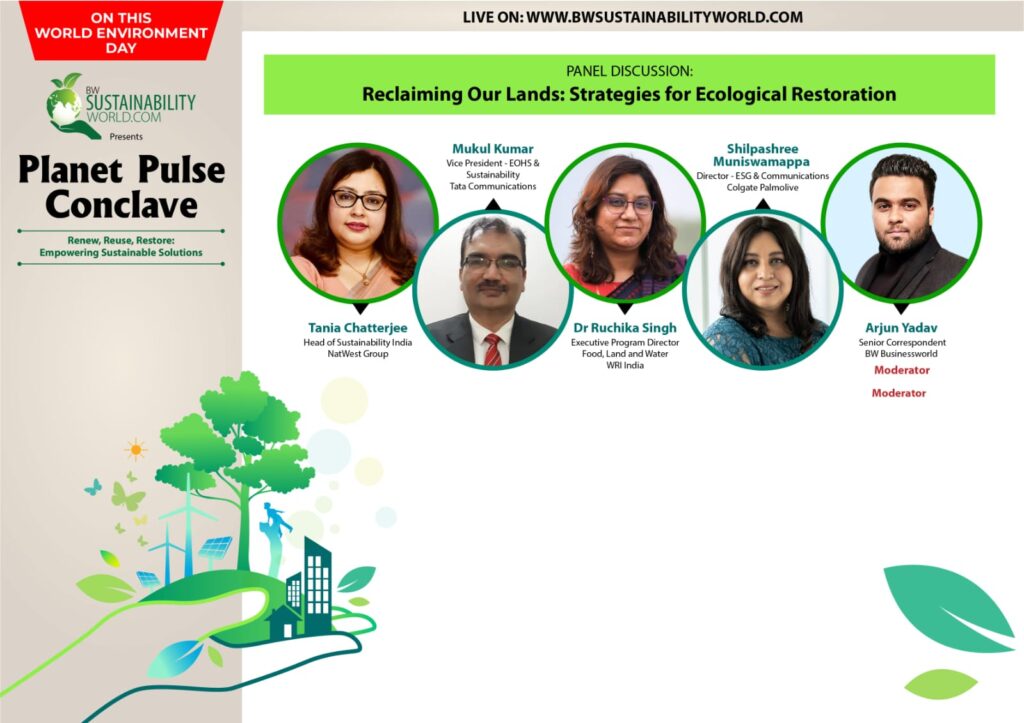

Scaling Standards Through Inclusion

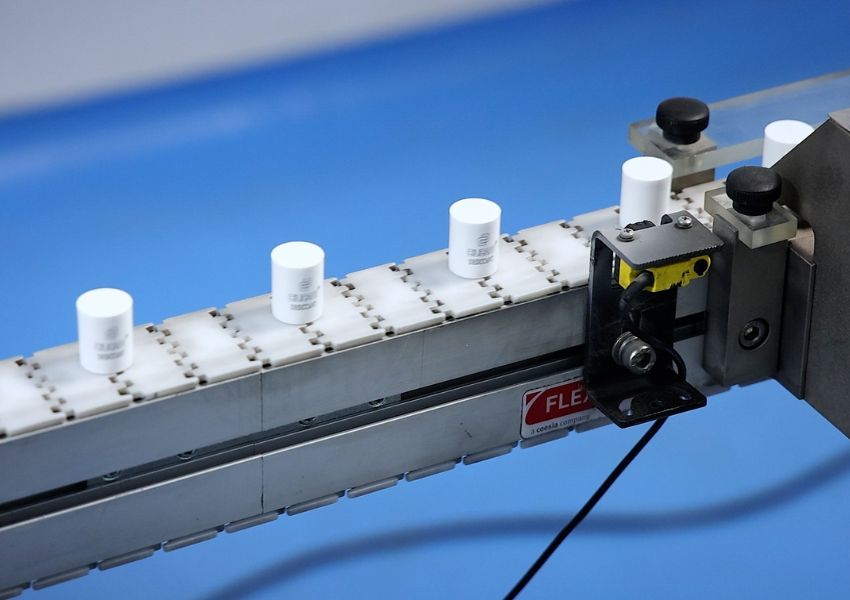

Indonesia has long stood as the epicentre of global palm oil production, accounting for nearly 85 per cent of global supply. Today, over 5.24 million hectares of plantations are certified under the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) system, producing more than 38 million tonnes annually (European Forest Institute). These are not minor numbers. They reflect a national framework that continues to expand and mature, with growing emphasis on sustainability at scale. Within this progress, smallholder farmers remain central. According to the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (INDEF), around 40 per cent of Indonesia’s palm oil is cultivated by smallholders who are deeply embedded in the future of the industry. Many continue to work within systems where land recognition, access to finance, and technical support are still being strengthened. Ensuring that these producers are able to fully participate in certified, sustainable supply chains is key to making national progress inclusive and lasting.

As certification efforts in Indonesia advance, participation is widening and monitoring systems are becoming more robust. Sustainability is applied consistently, especially in smaller and more varied production settings. Strengthening that foundation not only makes progress more inclusive, but it also reinforces Indonesia’s position as a trusted supplier in a world that increasingly values both scale and responsibility.

India: From Buyer To Co-author Of The Future

India being the world’s largest importer of palm oil, with nearly 60–70 percent of its edible oil imports being palm-based shapes the entire demand horizon. Thus, its purchasing decisions send signals that stretch far beyond its borders, directly influencing how palm oil is cultivated, processed, and certified in producing countries like Indonesia.

This connection is real and ongoing. When Indian buyers prioritize traceable, responsibly produced palm oil, it creates a market incentive for producers in Indonesia to meet that expectation. In a global system where producers often operate on tight margins, this kind of demand-side clarity becomes vital.

Indonesia, with its established certification frameworks and expanding monitoring capabilities, is well positioned to align with such expectations. But the momentum must be mutual. Palm oil sustainability has never been the responsibility of producers alone. It is co-authored and shaped by both the supply strategies in Indonesia and the procurement values set in India.

A Shared Architecture For Palm Oil Reform

Indonesia and India, being the two major players in the global palm oil market, are perfectly positioned to start a new chapter of sustainability. The new chapter would be one that is formed through South–South cooperation rather than external imposition. What is important now is not the abstract idea of alignment, but the practical systems that provide the opportunity for accountability.

In Indonesia, the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) is the primary system, which is rapidly expanding however, it is not the only system. Many producers in addition to ISPO also register their products under other standards such as the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC), which is a globally recognized system for the identification of sustainable bioenergy and biomass supply chains. These certifications showcase Indonesia’s ability to complete the international expectations, without the need for the introduction of similar frameworks.

In line with this, Indonesia has also participated in many co-operative research projects where the goal is to bring ISPO in harmony with RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil), a multi-stakeholder initiative that brings together producers, buyers, and NGOs. These pilot projects of cooperation that are often supported by allies like the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) actually provide a ground-level platform for awareness and further cooperation. Moreover, Indonesia is the directing force in the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC), an intergovernmental body that was inaugurated with Malaysia to unify the sustainability efforts and to represent the interests of producing nations in this matter. These discussions of CPOPC are like a platform upon which the collaboration between the countries of the South could be made more profound, one that India can also join directly as a strategic partner.

On its part, India has also made significant moves. Via the National Mission on Edible Oils – Oil Palm (NMEO-OP), the country is working to raise oil palm plantations in the domestic market along with implementing green practices in the production process. ICFRE, the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, is one of the agencies that are on ground to carry out the ecological impact assessment.

By anchoring collaboration in the existing mechanisms from ISCC and RSPO in Indonesia to NMEO-OP in India, both countries can construct a shared sustainability architecture that is credible, regionally rooted, and politically balanced. No new infrastructure is needed, just mutual recognition and a commitment to working through the systems that are already on the ground.

External Pressures And The Internal Resolve

Indonesia is directing an increasing share of its palm oil toward domestic biodiesel production, as part of its broader energy strategy under the B40 mandate. This shift reflects a national priority to strengthen energy independence and add value locally. But even with greater internal use, Indonesia remains one of the world’s largest exporters, and India continues to be one of its most significant trade partners. This evolving balance makes coordination more important.

As domestic allocation rises, volatility in international supply could become more common. For India, which remains heavily reliant on palm oil imports, this introduces questions not only of availability but of long-term reliability. In that context, shared planning around procurement, pricing, and sustainable sourcing becomes more than a matter of ethics—it becomes a strategy for economic stability.

From Transaction to Transformation Indonesia and India can lead not by replicating imported models, but by building a shared system that works on our terms: one that balances production with protection, scale with fairness, and trade with trust.

If the foundation is strong, rooted in transparency, inclusion, and joint responsibility, then palm oil can move from being a symbol of contradiction to a model of sustainable cooperation. This is not just about proving what is possible in palm oil. It is about showing what meaningful South–South partnership can look like when shaped with intention and led with purpose.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication