Aravallis: How the New Definition May Recast NCR’s Development Prospects & Ecological Stability

The Supreme Court’s move aims to standardise mapping and mining rules, but experts warn the narrower criteria may erode natural buffers that support groundwater, biodiversity and climate resilience in NCR

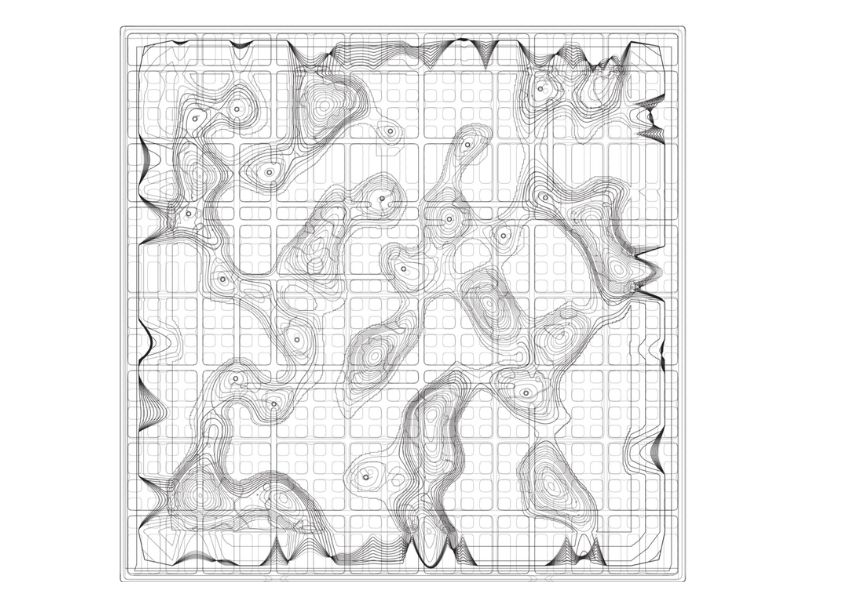

The Supreme Court, in an order dated 20 November, approved a revised definition of the Aravalli ranges, classifying a hill as any landform within notified districts that rises at least 100 metre above local relief and grouping such features into a range if they fall within 500 metre of each other.

Alongside the new definition, the Court imposed a freeze on fresh mining leases across four states until a scientific, region-wide plan for sustainable mining is prepared. It directed the Ministry of Environment to develop this framework through the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, mandating a clear demarcation of inviolate zones and areas where mining may be allowed only under exceptional circumstances. Existing operations may continue, but only under strict adherence to the guidelines that will follow.

The change represents an attempt to introduce uniformity in a landscape long marked by overlapping interpretations, contested boundaries, and inconsistent enforcement. Industry groups have called it an opportunity for regulatory clarity, while conservationists have argued that the height threshold will exclude most of the range’s ecologically active terrain.

Risk of Long-term Ecological Loss

Vijay Dhasmana, an ecological restoration practitioner, said the change reverses earlier progress on scientific identification. He pointed to a 2010 Supreme Court directive instructing the Forest Survey of India to map the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan using field-observable slopes and landforms.

“FSI found after ground truthing in Alwar district that the three-degree slope accurately covers the hills as shown by Survey of India maps and ground truthing,” he said. The mapping exercise identified more than four lakh hectares of land in the Aravalli hills across 15 districts. “Now, as per the report by IE, more than 90 per cent of the hills identified as Aravalli hills by FSI in Rajasthan will be excluded by definition. Roughly 12,081 hills will lose the Aravalli tag/protection and run the risk of mining and real estate pressure. It undercuts all zoning and development restrictions as these areas will not be Aravallis anymore.”

He said the hills and associated dunes support groundwater recharge in a region already facing a structural shortage. “NCR will face a huge pollution issue, these small hills and sandy dunes that are high groundwater recharge zones, so already scarce groundwater will further deplete,” he said.

He added that long-term desertification could have a damaging effect on agriculture and settlement patterns. Loss of habitat could also change wildlife movement, increasing the chances of conflict, especially in areas with no protected reserves. “Haryana has no protected areas in the Aravallis; the possibility to give haven to wildlife such as leopard, hyena and other endangered animals reduces considerably.”

Balancing Growth and Ecology

From the development industry’s perspective, the new definition promises simpler approvals and fewer disputes. Kesari Infrabuild Managing Director, Minal Srinivasan, said the change could ease the design of infrastructure across peripheral districts.

“The revised definition of the Aravalli range is expected to unlock new avenues for planned development and infrastructure expansion in NCR and surrounding regions. With clearer boundaries and fewer ambiguities, builders may find it easier to obtain approvals for responsibly designed projects, boosting economic activity and improving connectivity,” she said.

Srinivasan added that developers must comply with environmental norms, water management standards, and green building codes, treating them as part of basic project design rather than afterthoughts. She said the outcome would depend on implementation.

“Any change connected to the Aravalli ecosystem must be approached with extreme sensitivity, as the range plays a critical role in groundwater recharge, air quality regulation, and biodiversity preservation across Delhi NCR,” she said.

She said a well-designed regulatory framework might help reduce illegal mining and unregulated construction, which have been the primary drivers of ecological decline. She added that builders still face administrative delays, gaps in infrastructure provisioning, and varying interpretations of environmental norms at the local level.

Future Of Aravalli Stewardship

The Court’s directive for a comprehensive plan has raised questions about what sustainable mining might look like in a landscape of scattered hills, wildlife corridors, and urban expansion. Dhasmana said meaningful sustainability would be difficult to standardise.

“Sustainable mining: to make this plan, we need to understand the context and the biodiversity of the particular hill to be mined. So, I see it as a case-by-case basis impact,” he said. He questioned the rationale of introducing a narrow definition when planning will be carried out across the full range. “What is the need for a new definition of 100 metre? It does not need any definition.”

The new definition may also attract constitutional scrutiny.

Jotwani Associates Co-Managing Partner, Dinesh Jotwani, said the Court accepted the definition after a multi-stage process of expert submissions, but concerns raised by petitioners remain relevant. He said environmental protection has been part of the Court’s jurisprudence for decades, and any dilution may be challenged. “If the new definition is narrower, excluding ridge extensions, isolated rocky outcrops, or ecologically connected areas, it risks contradicting the Court’s prior ecosystem-centric approach,” he said.

He said possible grounds for challenge include arbitrariness, infringement of the right to a healthy environment, and non-compliance with earlier directives. “If petitioners produce credible scientific data showing that the revised definition weakens environmental protection or excludes ecologically vital areas, the Court may order a review or reconsideration by an independent expert panel.”

Meanwhile, the verdict comes at a time when NCR is grappling with severe air pollution, rising heat and rapidly declining groundwater, pressures that increasingly shape land use, infrastructure planning and investment decisions. While the proposed sustainability plan may bring order to mining activity, it must reckon with the smaller ridges, rocky outcrops and scrub zones that underpin water recharge and wildlife movement.