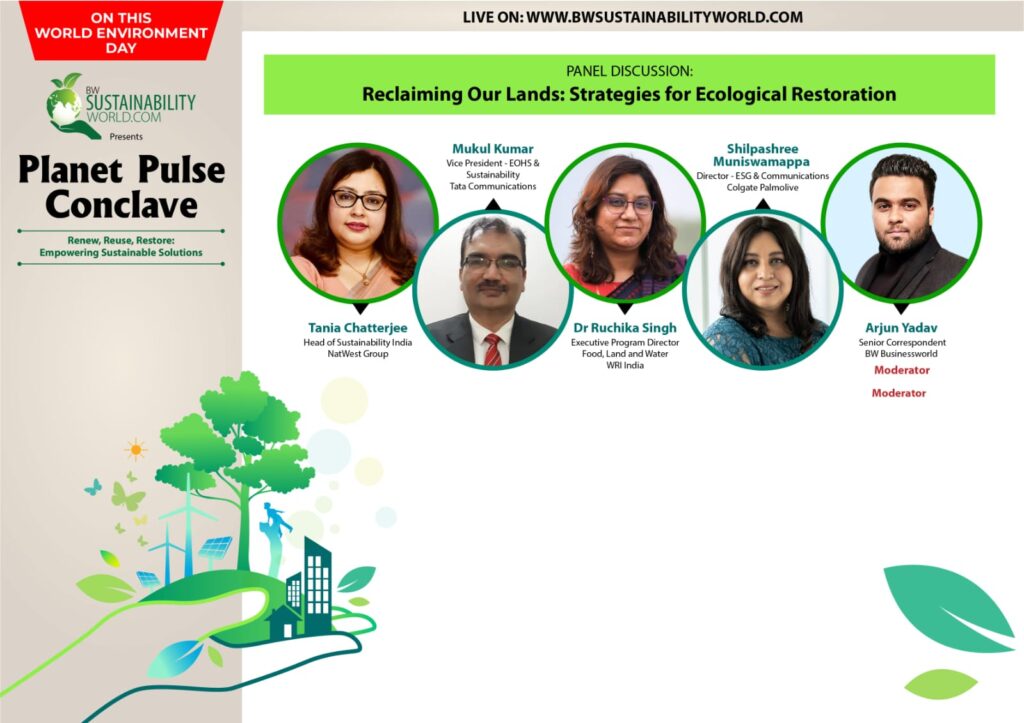

Climate Risks Threaten South Asia’s Poverty Reduction Gains

A UNDP Oxford study warns that despite major strides in reducing multidimensional poverty, nearly all poor households in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal remain vulnerable to rising heat, floods, drought, and air pollution

The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) Report 2025, released by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the University of Oxford, paints a stark picture of how the climate crisis is reshaping poverty worldwide. Despite unprecedented progress in poverty reduction, it finds that South Asia’s poorest communities are now trapped at the frontline of intensifying climate hazards.

Globally, of 6.3 billion people across 109 countries, 1.1 billion – or 18.3 per cent – live in acute multidimensional poverty. Of these, about 887 million people (78.8 per cent) already live in areas facing at least one of four major climate hazards: high heat, drought, floods, or air pollution. The overlap between poverty and climate exposure is most severe in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

South Asia: A Success Story Under Threat

South Asia stands out as both a success story and a warning signal. While the region has recorded some of the world’s fastest poverty reductions, almost all its poor remain exposed to environmental extremes. India’s Poverty and Equity Briefs (PEBs), released by the World Bank in April 2025, highlighted that India has successfully lifted 171 million people out of extreme poverty. Its consumption-based Gini index improved from 28.8 in 2011-12 to 25.5 in 2022-23, indicating a reduction in income inequality.

But all these developments are threatened as the UNDP MPI report estimates that 99.1 per cent of the poor population in South Asia – about 380 million people—live in regions affected by at least one climate hazard. Over 91.6 per cent (351 million) face two or more, and 59 per cent (226 million) are exposed to three or four hazards in the same year.

Across India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, poverty overlaps strongly with high heat, flooding, and air pollution. Other regions, such as West Africa, northeastern Brazil, and parts of East Asia, also show similar intersections, but South Asia’s scale and density of exposure are unmatched. The catastrophic disasters were quite visible as Punjab faced its worst crisis in decades, as floods devastated both the landscape and livelihoods across the state. Dharali flash flood in Uttarakhand, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa flash floods in Pakistan are some other examples.

In 2024, Asia recorded the highest number of natural disasters worldwide – more than 160 – including storms, floods, heat waves, and earthquakes, according to the Emergency Events Database of the University of Louvain in Belgium. Researchers estimated the resulting losses at more than USD 32 billion. According to media reports, an analysis by the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) found that infrastructure worth USD 124 billion in Nepal is at risk from climate-induced disasters

The current MPI report warns that countries with higher current poverty levels are likely to face greater temperature increases, with projections suggesting 37 more high-heat days per year by 2040–2059 and as many as 92 additional days by 2080–2099 under a high-emissions scenario.

Strong Poverty Reduction Continues

Despite these vulnerabilities, South Asia’s record in reducing poverty remains exceptional. UNDP’s MPI report found that India’s poverty rate fell from 55.1 per cent in 2005–06 to 16.4 per cent in 2019–21, lifting around 414 million people out of poverty. Bangladesh saw its rate decline from 30.5 per cent in 2014 to 11.5 per cent in 2022, enabling 28.7 million people to escape deprivation. Nepal reduced poverty from 58.3 per cent in 2006 to 16.4 per cent in 2022, with 10.6 million people moving out of poverty.

The UNDP–Oxford report called these ‘momentous reductions’ that have driven global progress, showing that rapid poverty reduction is possible even in large, lower-middle-income economies. However, it cautions that the poorest in South Asia now face an overlapping crisis, as climate shocks threaten to erode these gains. The report concludes that South Asia, which once led the world in scaling down poverty, must now pioneer a new model of growth—one that combines determined poverty eradication with climate-resilient development strategies.