COP30: Climate Finance, Forests And Frontline Anger Take Centre Stage In Week 1

A record turnout, new finance pledges and rising frontline anger marked the opening week of COP30 in Belém, Brazil, with India watching the climate finance, forest and carbon market debates closely as they shape the space for developing countries.

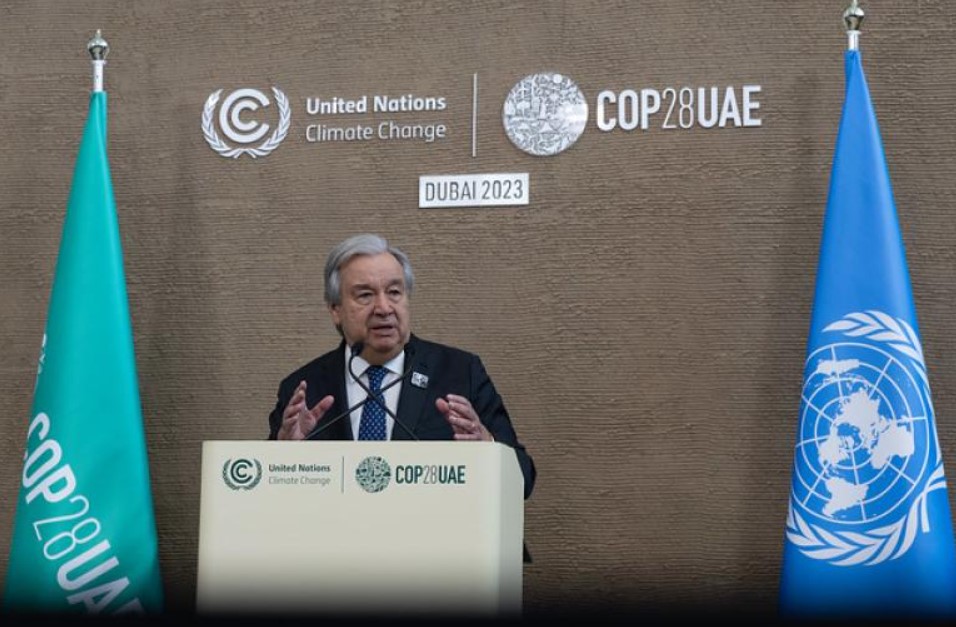

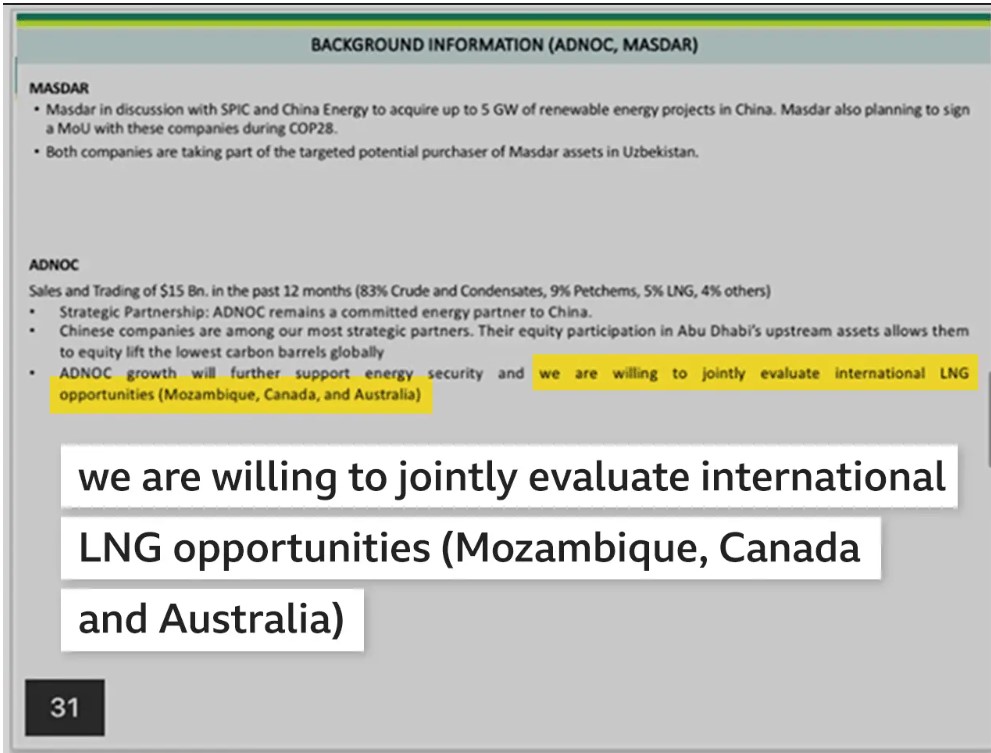

COP30 officially started on Monday, 10 November in Belém. With more than 56 thousand delegates registered, COP30 is provisionally the second-largest COP in history, behind only COP28 in Dubai, which was attended by more than 80,000 people. Some 1,600 participants, one in every 25, are fossil fuel lobbyists, according to Kick Big Polluters Out. Representatives from the fossil fuel and meat industries are also in attendance.

Brazil and China sent the biggest delegations, 3,805 and 789 delegates respectively, according to Carbon Brief. For the first time in 30 years, the US federal government sent no delegation, a move in line with the Trump administration’s anti-climate stance. Aside from President Donald Trump, other world leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping and those of Russia and Japan, Australia, Indonesia and Turkey, are also set to skip the summit. California Governor Gavin Newsom attended as part of a state-level delegation.

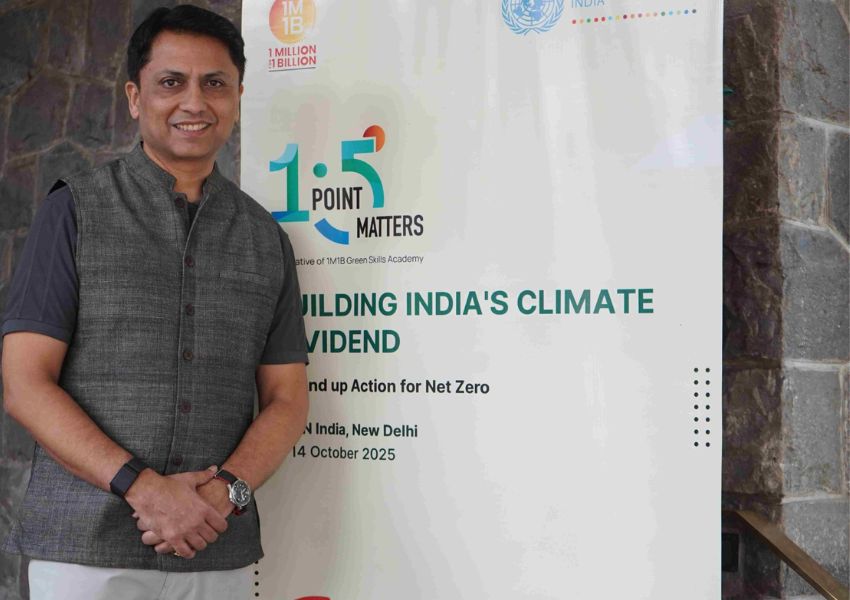

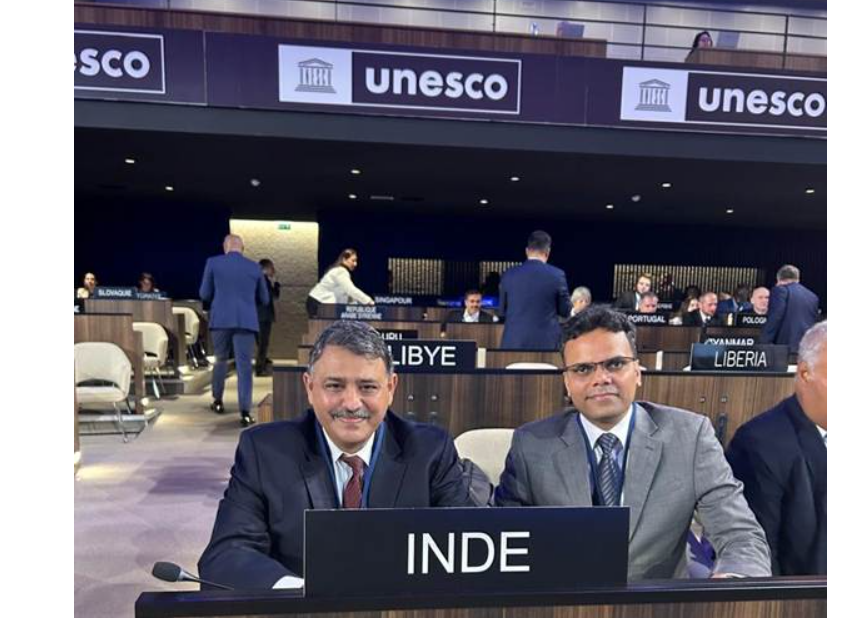

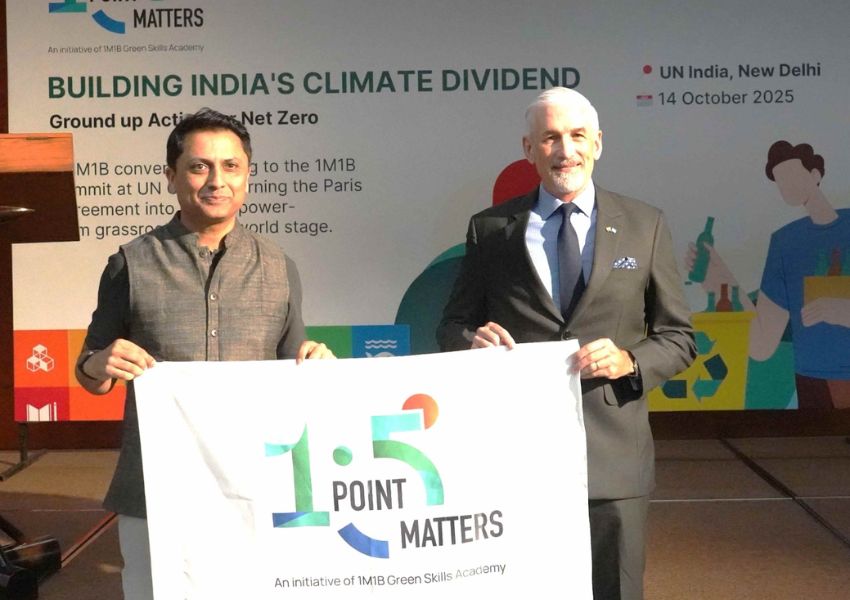

For India, Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav is leading the delegation at COP30 in Belém, Brazil. Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi is not attending, Indian Ambassador to Brazil Dinesh Bhatia is representing India at the Leaders’ Summit. Amandeep Garg, Additional Secretary at the Ministry of Environment, is India’s lead negotiator, focusing on adaptation, climate finance, and other key issues that will determine how much predictable support large developing economies and vulnerable countries can expect over the next decade.

Loss, Damage And The Developing World

On Monday 10 November, a long-sought fund for responding to climate change-caused loss and damage introduced its first call for project proposals, with the initial package totalling USD 250 million. Countries vulnerable to climate change have six months to submit funding approvals from mid-December, with grants of up to USD 20 million per project expected to be disbursed from mid-2026.

The Loss and Damage Fund was introduced at COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh but sat mostly empty until now. In March, President Trump withdrew the US from the fund’s board. It was not clear from the letter whether this also meant the country was pulling out entirely from the fund, which is hosted by the World Bank.

As of 30 June, a total of USD 788.80 million has been pledged to the fund, mostly from European countries. USD 17.5 million came from the US. For India and other developing countries, how quickly this money is operationalised, and whether new and additional resources follow, will be central to trust in the wider finance package emerging from Belém.

Trillion-dollar Roadmap And Health-climate Finance

Last week, the UNFCCC issued the Report on the Baku to Belém Roadmap to USD 1.3 trillion. The document aims to “provide a coherent action framework reflecting initiatives, concepts and leverage points to facilitate all actors coming together to scale up climate finance in the short to medium term.” It outlines five “action fronts” to help deliver on the USD 1.3 trillion aspiration, incorporating regional considerations, with a deliberate focus on addressing the needs of the poor and particularly vulnerable, including small islands, developing states and least developed countries. It also sets out short-term deliverables.

Meanwhile on Thursday, the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG) laid out what it calls an “entirely feasible path” to mobilising USD 1.3 trillion in climate funding for developing countries by 2035. It comes as negotiations on a pathway to scale up climate finance from a large variety of sources, from last year’s roughly USD 300 billion flows to USD 1.3 trillion, are underway.

The group, chaired by economist Nicholas Stern, says about half of the USD 1.3 trillion could be met by the private sector.

On Thursday, a coalition of more than 35 leading global philanthropies announced a joint USD 300 million commitment to tackle the escalating public health crisis driven by climate change. Funders include Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Gates Foundation, Wellcome, Rockefeller Foundation, IKEA Foundation and CIFF. “The immediate focus for the first USD 300 million will be to accelerate solutions, innovations, policies and research on extreme heat, air pollution and climate-sensitive infectious diseases. The funds will also strengthen the integration of critical climate and health data to support resilient health systems that protect people’s lives and livelihoods,” according to a press release.

Meanwhile, a report published this week by the ClimateWorks Foundation found that philanthropic funding for climate adaptation and resilience efforts worldwide reached USD 870 million last year, a historic high. For India, which faces rising health risks from heat and air pollution, these arrangements signal an emerging architecture in which health, climate and development finance are increasingly interlinked.

Forest Funds, Land Rights And Carbon Markets

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva last week announced his flagship initiative to pay for forest conservation, known as the Tropical Forest Forever Fund. Fifty-three countries have endorsed the fund, but its initial investment target of USD 25 billion was cut back significantly, with only five other nations, Norway, Indonesia, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands, committing significant money. A total of USD 5.5 billion have been pledged so far.

China has reportedly declined to invest in the fund, arguing that developed nations should bear primary responsibility.

A dozen countries have pledged to formally recognise land rights across 80 million hectares inhabited by Indigenous, Afro-descendant and other communities by 2030.

Another one of Lula’s flagship initiatives at COP30 is a coalition aimed at improving collaboration on carbon markets by aligning practices and standards. The European Union and China joined it last week, along with the UK, Canada, Chile, Armenia, Zambia, France, Mexico and Germany. “Brazil believes that integrating carbon markets could be one of the most important legacies of COP30 as it would facilitate trade and ultimately help to curb emissions,” according to Bloomberg.

These moves on forests, land rights and markets are being watched in New Delhi for their implications for South–South cooperation, jurisdictional forest finance and the future shape of compliance and voluntary carbon markets that Indian firms and state governments are seeking to tap.

Protests, Indigenous Representation And Information Integrity

The Brazilian government has underlined “unprecedented” Indigenous participation at COP30, with around 2,500 Indigenous people in Belém and Indigenous rights formally placed at the centre of the talks. In practice, however, only about 14 per cent, or 360 people, obtained accreditation for the Blue Zone, the tightly controlled area where formal negotiations take place, according to InfoAmazonia.

“It is expensive and hard to get accreditation. In my region, only two people received it. They are not interested in hearing from those who truly need to be heard,” said Lucas Tupinambá of the Tapajós-Arapiuns Indigenous Council, who travelled two days by boat to attend the summit.

Frustration spilled over on Wednesday, when Indigenous protesters forced their way into the venue and clashed with security guards in what Politico described as the “most serious act of unrest seen in years” at a COP. The demonstrators demanded meaningful representation in decision-making spaces, arguing that their territories have long borne the brunt of resource extraction.

On Friday, around 90 Munduruku Indigenous protesters blocked the main Blue Zone entrance for about an hour, prompting the deployment of army personnels. At the same time, climate campaigners targeted the COP30 “AgriZone”, a dedicated space sponsored by Nestlé and Bayer for agribusiness interests. Activists from the Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice warned that the zone symbolised the growing capture of UN climate talks by large polluters. Industrial agriculture drives roughly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions and is a major cause of Amazon deforestation, they noted, citing recent assessments.

“It is deeply concerning to see a third zone popping up at COP30 dedicated entirely to agribusiness interests,” said Elodie Guillon of World Animal Protection, calling industrial animal agriculture both a leading source of emissions and a cause of “deforestation and farmed and wild animal suffering”.

Against this backdrop, governments and UN agencies Introduced a Declaration on Information Integrity on Climate. So far 12 countries, including Brazil, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, have signed on. The text urges states to protect journalists and scientists, guarantee public access to climate data and press technology and advertising companies to curb disinformation.