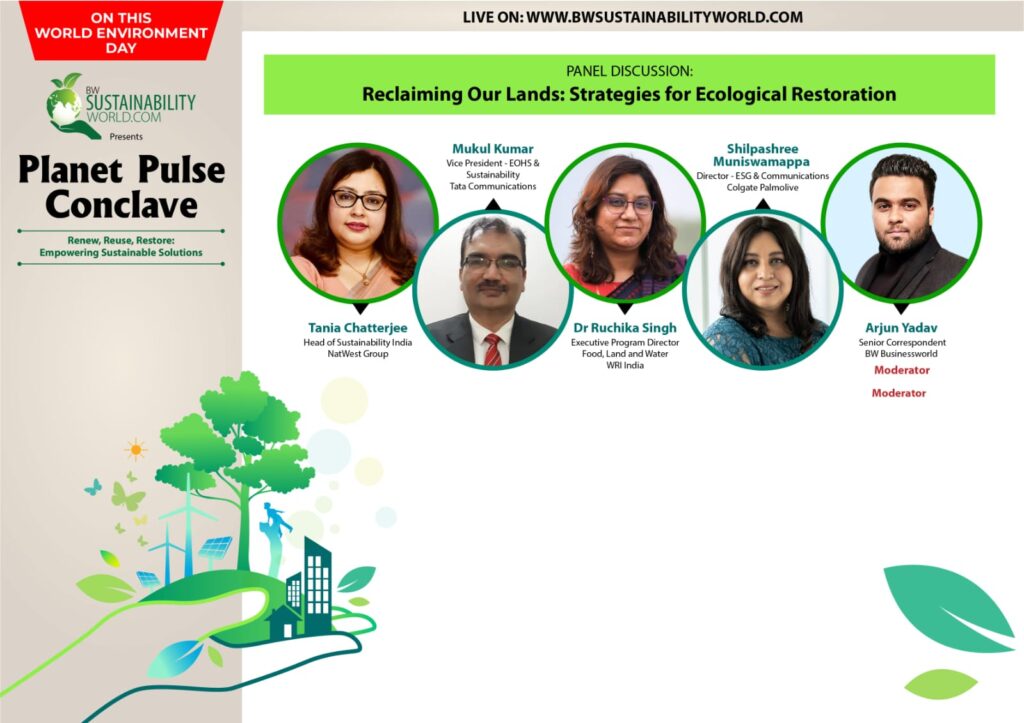

For Carbon Markets To Work In India, They Must Be Made In India

The Indian Carbon Market part of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme will decarbonise high emitting sectors while enabling economic growth

Byline: Yashodhan Ramteke, Head-Carbon Business Unit, MMCM

India has set two equally big and necessary goals: become a USD 5 trillion economy and net-zero by 2070. The nation’s updated NDCs for 2030 reflect this balancing act-reduce emissions intensity of GDP by 45 per cent from 2005 levels and 50 per cent cumulative electric power capacity from non-fossil sources. The Indian Carbon Market (ICM) part of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) will decarbonise high emitting sectors while enabling economic growth.

The intent is clear: industries must transition without choking growth. But if designed poorly a carbon market can become a compliance burden that slows innovation rather than accelerates it.

Already India has issued 278 million voluntary carbon credits; ranking 3rd globally; but verified emission reductions are sparse. This is a big warning sign that credits should not be just numbers on paper but drivers of real environmental and economic transformation.

A carbon market that sounds good on paper but fails on the ground will slow down every industry it’s meant to disrupt.

Imported Models Don’t Fit Here

Western carbon markets, like the EU ETS or Japan’s schemes, which emerged in controlled, homogeneous industrial settings with robust enforcement, uniform data systems, and high per-capita emissions. India’s industry is the opposite: a mix of legacy industries, MSMEs, informal sectors and vast geographical diversity.

Per capita emissions remain low (~2 tCO₂/year), yet industrial emissions are rising rapidly. Verification-heavy models suited to Europe would be nearly impossible to implement across India’s decentralised manufacturing belts. The country needs adaptive designs that reflect its own realities.

Traditionally, the carbon market and the methodologies in the carbon market were driven by the West, where the issues and challenges are quite different than in India. A lot of projects which have additionality in India or developing countries may not be additional in the Western countries.

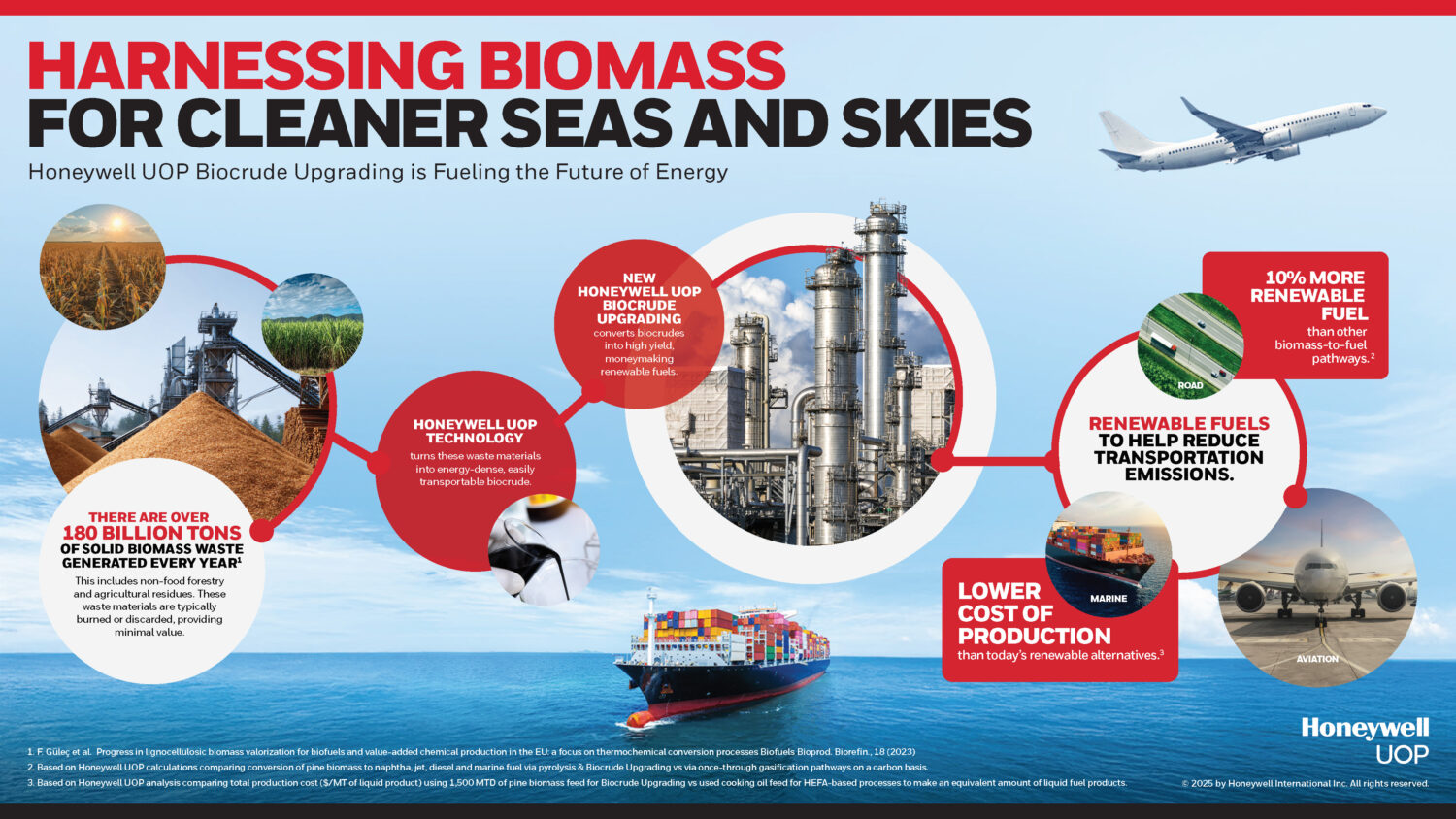

Let’s take the example of the recycling sector in India and the West. In India, most of the recycling happens in the informal industry, whereas the West has a well-developed recycling industry, so there is no need of climate or carbon finance.

With over 60 million MSMEs contributing ~30 per cent to GDP; many without formal carbon accounting; India cannot simply borrow a template. It must build a system that meets industries where they are.

A carbon market is not about emissions, but context. And India’s context is too messy for copy-paste solutions.

The Market Must Be Industry-First, Not Policy-First

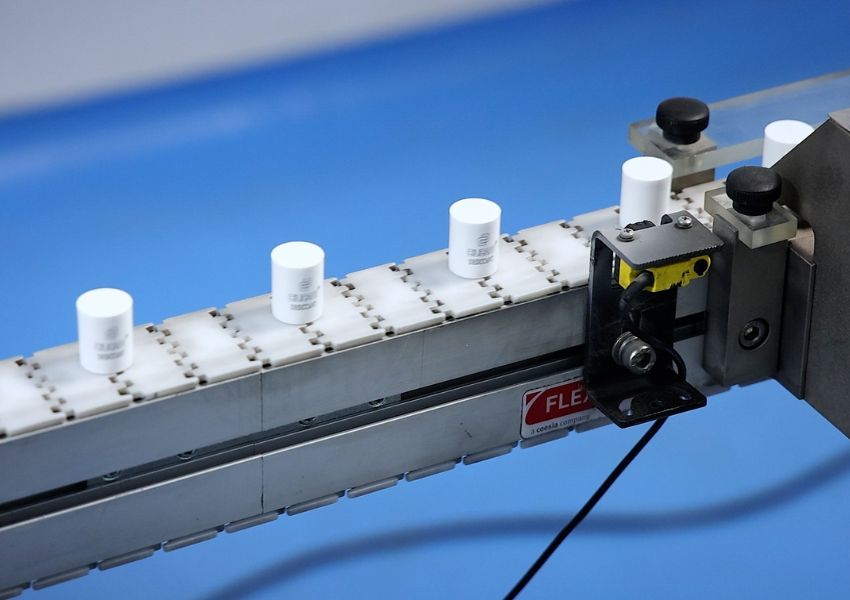

India’s carbon market will succeed only if it works for the industries that will drive decarbonisation, steel, cement, power, aluminium, fertilisers and more. These sectors are already familiar with efficiency measures under the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) programme which has cut CO₂ by 87 million tonnes between 2012 and 2020. But low trading volumes show a key lesson: even well-intentioned policies fail without usability and economic appeal. The Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) framework must be: tech enabled with minimal friction, affordable and accessible, scalable for tier 2 and tier 3 cities and industrial clusters.

For MSMEs, compliance should be plug and play; not an administrative maze. And carbon credit prices must be stable and predictable to encourage participation and investment. For a carbon market to succeed, its user experience must feel like a transaction, not a tribunal.

The Real Opportunity: Aligning Growth with Decarbonisation

Carbon pricing if correctly done will not hinder growth; it will accelerate the same. Revenue and market incentives can drive investment in green hydrogen, clean energy, circular economy and industrial heat electrification. It will also make Indian exports competitive, allowing them to bypass charges under initiatives such as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) which can affect up to over USD 825 billion worth of exports by 2026.

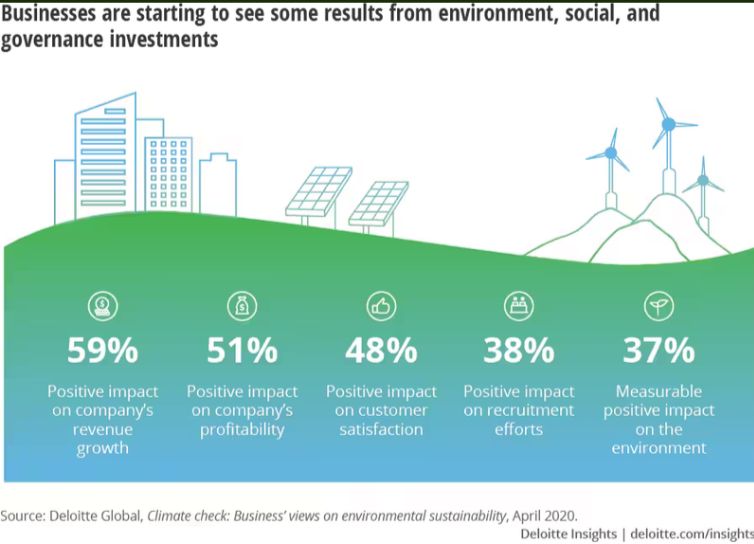

A well-structured carbon market must be tied to larger ESG goals and green finance streams so that compliance is an opportunity rather than an expense. For India’s clean-tech industry, it can be both a financial metric and a confidence driver, triggering innovation across industries.

The carbon market must not be perceived as a climate penalty; it must be an instrument of competitiveness.

Conclusion: It’s Time to Build, Not Borrow

India can and should develop a carbon market that’s mirrors its industrial ground realities, decentralised economy, and development imperatives. A strong, inclusive and scalable platform can be a template for other comparable emerging economies.

A copy-paste carbon market might tick boxes. A custom-built one could change the game. The success of India’s carbon market won’t lie in how well it mimics the West; but in how well it mirrors India.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.