Green Hydrogen’s Next Frontier In India: Overcoming Cost & Scale Challenges

To ensure scale, India must rapidly establish dedicated green hydrogen industrial hubs, transparent regulatory frameworks, and secure off-take agreements

Byline: Vivek Agarwal, Global Policy Expert, Country Director, -Tony Blair Institute For Global Change

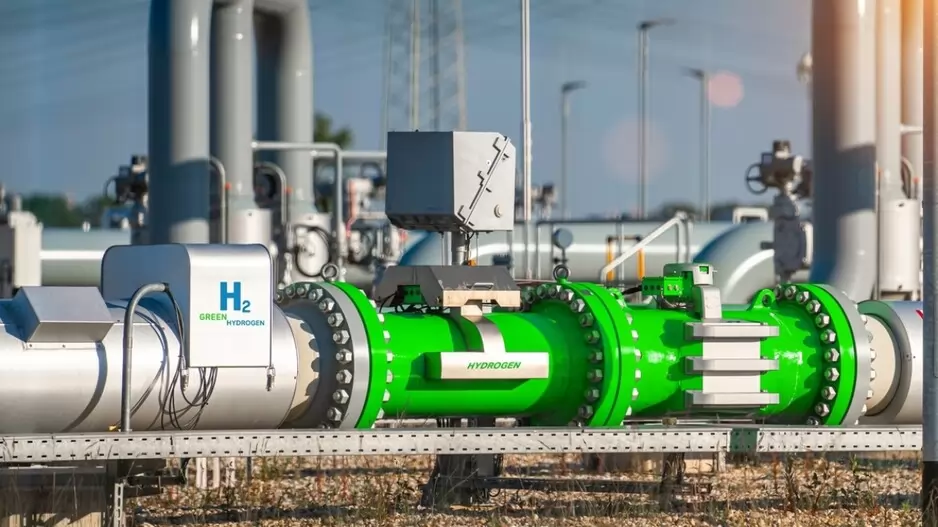

India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission aims to establish the country as a global leader in green hydrogen. Unlike ‘grey’ hydrogen, ‘green’ hydrogen is hydrogen produced by splitting the water molecule using renewable electricity, emitting no greenhouse gases. This initiative is as aspirational as India needs to meet its climate commitments, strengthen its energy security, and capture a share of the global clean-energy market. However, ambition alone does not ensure success. As India starts its green hydrogen journey, it can learn much from its solar energy experience. Still, some key differences must not be overlooked.

About a decade ago, solar energy in India was widely considered economically unviable and technically challenging. In 2010, at the start of the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission, solar tariffs exceeded Rs 17 per kilowatt-hour, nearly prohibitive compared to coal-based electricity. Yet today, India’s solar tariffs have dropped below Rs 3 per kilowatt-hour, making India a global leader in affordable solar power. This turnaround was no accident. But instead, it was driven by strategic policy intervention that produced economies of scale. Once solar reached cost parity, it became not only competitive but unstoppable.

Achieving Cost Parity

Today, green hydrogen stands precisely where solar stood around 2010. Green hydrogen remains 2-3 times more expensive than fossil-based ‘grey’ hydrogen. To replicate solar’s success, green hydrogen costs must decline significantly and swiftly.

India’s low renewable electricity tariffs provide a strong starting point. Electrolysis, the process underpinning green hydrogen production, currently consumes 50–60 kilowatt-hours of electricity per kilogram. If leveraged effectively, India’s abundant and affordable solar and wind resources can dramatically reduce green hydrogen costs.

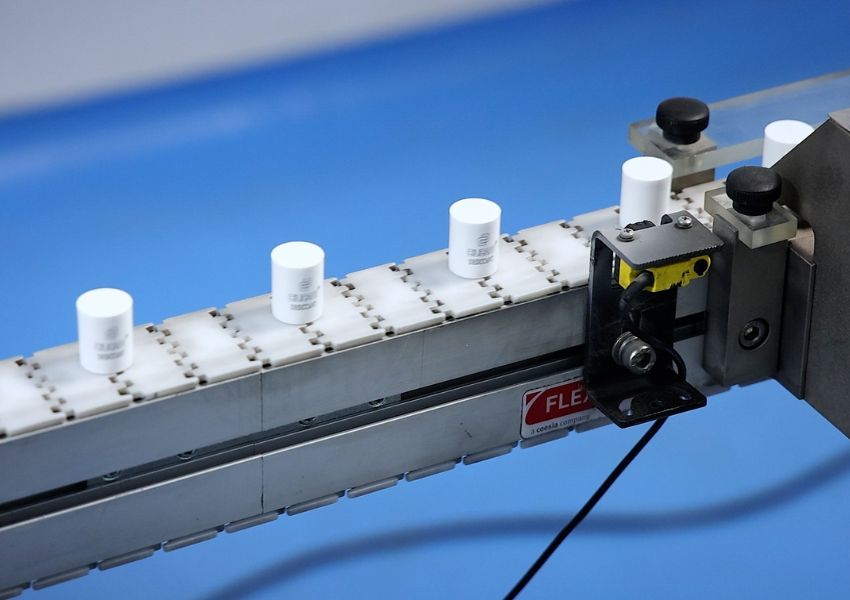

However, cheap electricity alone is not sufficient. A second critical factor – electrolysers, the specialised equipment used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen must experience the kind of rapid price declines that solar panels witnessed. Electrolyser costs account for a substantial portion of green hydrogen’s high price. Global electrolyser prices have dropped roughly 60 per cent over the past decade, and industry analysts predict a further 40–50 per cent reduction by 2030.

Recognising this, India’s government has rightly earmarked Rs 4,440 crore to boost domestic electrolyser manufacturing under the Rs 17,490 crore Strategic Interventions for Green Hydrogen Transition (SIGHT) program.

Scaling For Impact

But cutting costs is just one part of the challenge. Scaling production is a harder challenge. India aims to make at least 5 million metric tonne (MMT) of green hydrogen per year by 2030. That is bold, particularly considering current production levels. Achieving it would need roughly 60–100 gigawatts of electrolyser capacity and around 125 gigawatts of dedicated renewable energy – close to India’s entire current solar and wind capacity.

India’s solar scale-up succeeded because policymakers identified and targeted key market enablers: predictable demand, investor-friendly frameworks, dedicated infrastructure, and global collaboration. Green hydrogen demands similar, perhaps even greater, strategic clarity. To ensure scale, India must rapidly establish dedicated green hydrogen industrial hubs, transparent regulatory frameworks, and secure off-take agreements. Without firm demand commitments, mobilizing the estimated Rs 8 lakh crore in private capital will become prohibitively challenging.

Major Indian companies such as Reliance Industries and the Adani Group have pledged big investments in green hydrogen. International firms from Europe, Japan, and the Middle East have also shown interest. But the solar experience teaches us that pledges alone are insufficient. Concrete market rules – like mandating green hydrogen for refineries and fertilizer industries that already rely on grey hydrogen – are vital to transform big announcements into tangible projects.

Interestingly, India’s hydrogen policy includes an export-oriented approach, potentially allocating up to 70 per cent of early-stage green hydrogen production for global markets. This takes advantage of strong international demand in regions with carbon pricing and strict emission limits, achieving scale quickly without putting a heavy burden on domestic users. During India’s solar boom, exporting technology and drawing in international capital proved crucial. Applying that approach to hydrogen is logical and essential.

Building Distribution Infrastructure

Still, the solar-hydrogen parallel has limits. Solar power can feed into existing electricity grids, but hydrogen needs complex storage, transport, and safety systems that do not yet exist in India. Pipelines, storage tanks, distribution networks, and strict safety rules will require careful planning, large investments, and strong public-private collaboration. It is a complicated task that should not be underestimated.

Electrolyser manufacturing also depends on complex global supply chains involving critical minerals like platinum-group metals and nickel. Making procurement of these minerals geopolitically sensitive and prone to price swings. India must ensure varied supply sources, invest in local production, or form strategic international partnerships to handle these risks.

Because of these hurdles, fully reaching the 5 MMT annual goal by 2030 might be optimistic. Yet even hitting half that mark would place India among the world’s green hydrogen leaders.

India’s solar story shows that reaching an initial scale matters more than being perfect right away. Early breakthroughs attract global funds and show that the market works. Once challenges are overcome, growth can speed up. The next five to seven years are critical to test this strategy for green hydrogen.

If India matches its bold vision with strong execution again, green hydrogen could be the next renewable frontier for India, boosting national growth and global standing in the green economy. The groundwork is laid, and the lessons are clear. Can India seize this moment to match or even surpass its solar power success?