Harnessing Indian CSR Model For Climate Funding

The climate crisis isn’t looming on the horizon—it’s knocking on our front door. We are living in an era where the ramifications of our actions have never been more pronounced. But as we rush to respond to this crisis, a critical question looms – who foots the bill?

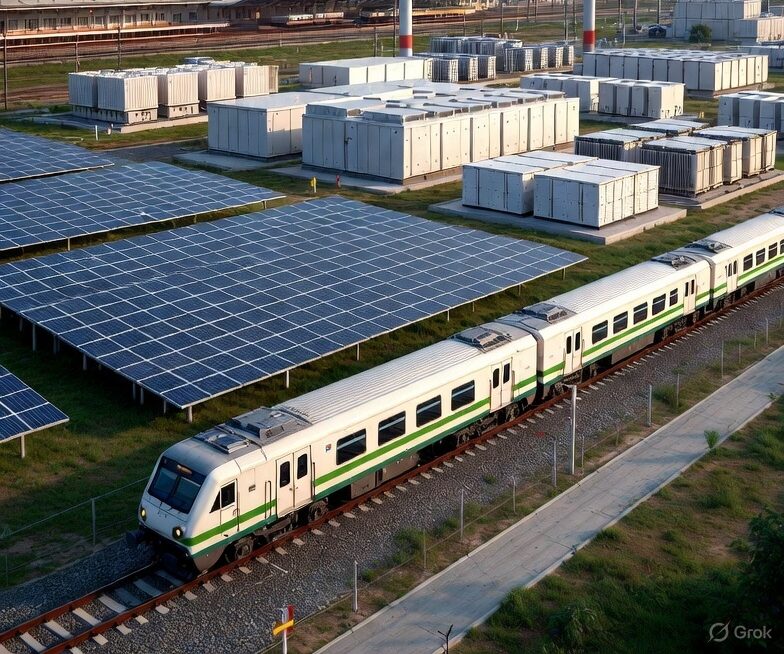

Mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change will undeniably require a huge investment. Between now and 2050, governments worldwide, and the private sector, are expected to need $131 trillion in investments for energy transition. For India alone, our investments towards a low-carbon transition and building climate-resilient infrastructure are estimated to be in the range of $7.2 trillion to $12.1 trillion by 2050. The key question is, should India (and by extension other countries of the developing world with lower emissions per capita) be the ones paying for this transition?

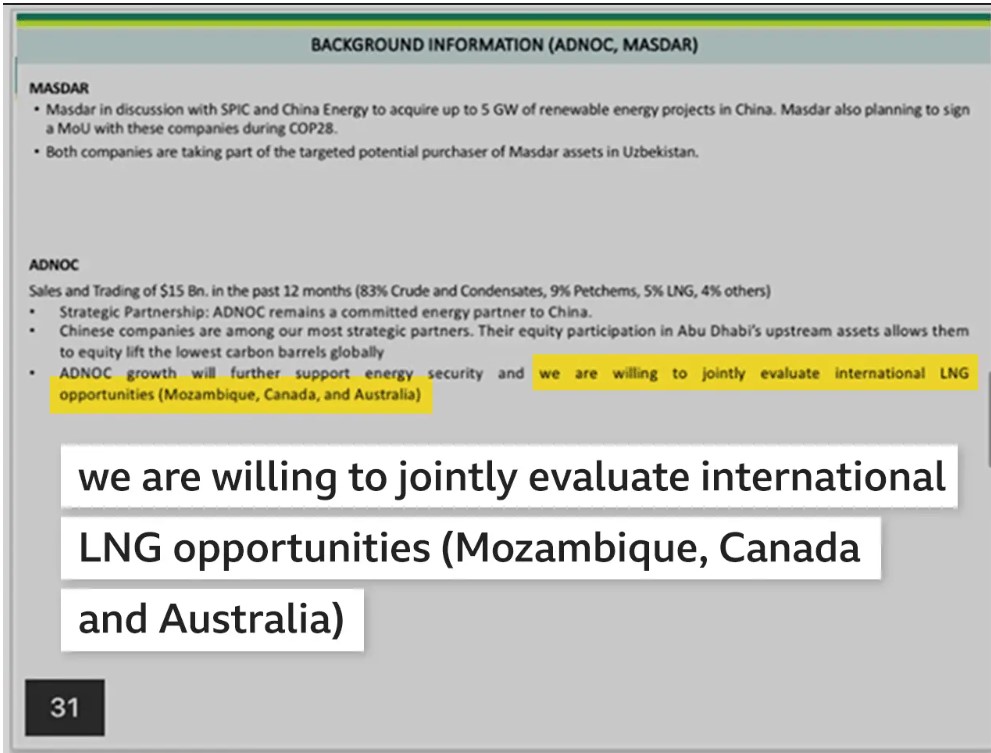

For starters, it is important the developed countries stay true to their word and commitments made at COP 15 in 2009 (UNFCCC, Copenhagen), and provide the promised funding towards decarbonisation. The discrepancy, lack of transparency or just plain non-disbursement of funds from the developed countries to support developing countries’ transition to low carbon growth pathways is glaring in its omission. Commitments were made decades ago but the flow of funds is a mere trickle, which is not due to a lack of capital, but low priority accorded to decarbonisation. To expect a short-term bulk commitment is naïve, but payments in tranches – to be made against achieving milestones are required to ensure accountability and correct usage of funds.

Further, it’s also important that these funds are not offered entirely in the form of debt funding, keeping developing countries in an endless cycle of repayment and also compromising their sovereignty. Rather a large portion should be offered as grants and aids. It is no secret that developed countries have benefited largely from the environmental, economic and social exploitation of developing countries and their prosperity today would not have been possible without this. For them to say that they are now willing to offer some of their dubiously gained wealth as a loan to generate more income in the form of interest isn’t just unfair, but grotesque. There’s no reason the “polluter pays” principle shouldn’t apply here, with the apportioning of responsibilities as per the per capita emission.

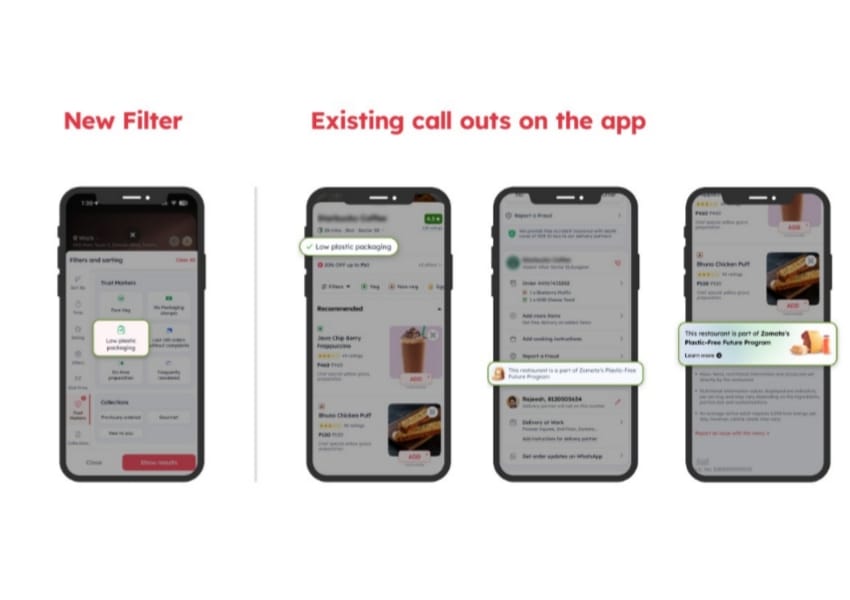

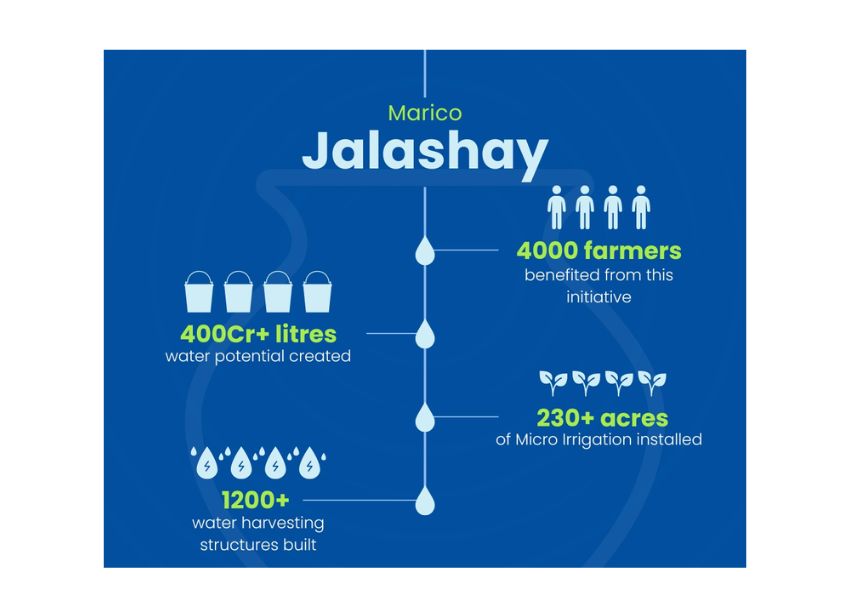

Having said that, it is important to check how these funds are utilised, and a proper governance mechanism to transparently monitor progress. The common refrain is that developing nations are generally more prone to corruption and hence will not utilise funds efficiently. While we need to rid of this patronising attitude, I fully endorse the need for an overarching monitoring and governance mechanism which is global, inclusive and as free of bias as possible. The Indian CSR model is a great example to emulate, where budgets, outcomes, milestones, audits and utilisation are built in as mandatory compliance.

These targets, tranches and milestones must also be bespoke – country specific preferably, based on the level of development, population and fiscal standing. For example, agriculture in India is one of the biggest contributors to emissions, hence projects in this sector will be prioritized, but for, say, Indonesia, it could be transitioning from fossil production to renewables. So countries could theoretically submit their funding requests with targets, timelines and strategies to achieve them. A global monitoring agency (created outside the current financial ecosystem) could then disburse funds and monitor progress.

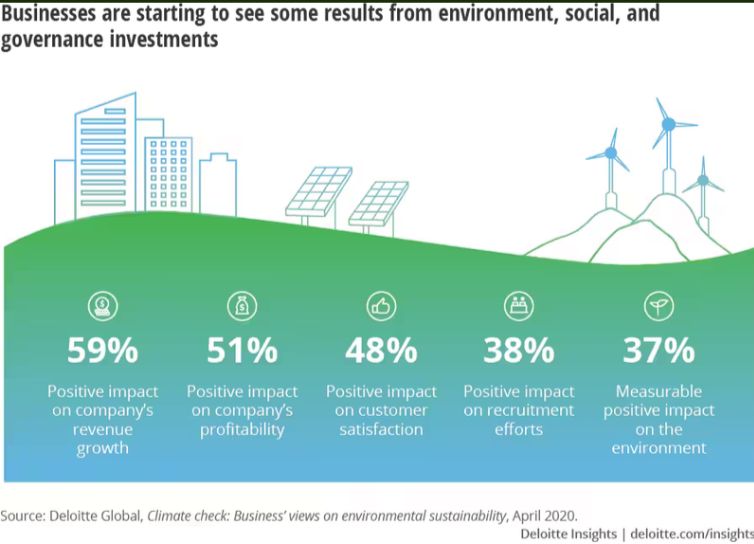

Then there will be those that demand from private finance and from corporates and how that should be primarily used to bridge the climate funding gap. While there is scope for private finance to expand its use in climate risk mitigation, companies are already investing significantly on reducing not just their own operational impacts, but from their value chain as well as part of their sustainable supply chain commitments. They are also increasing investment towards climate resilience and adaptation. Expecting them to shoulder the entire burden of financing climate transition would be disastrous for the companies and the economies in which they operate.

The bottom line is this – If the nations of the world fail to deliver on the promise they made to solve the climate emergency,

they are failing generations to come and the planet. The developed world cannot continue to pretend that their responsibility is shared equally and step up and do what is morally and ethically correct. The United Nations has clearly stated that the annual $100bn commitment, “is a floor and not a ceiling” for climate finance. We are past the stage where climate finance needs to be debated and we need to start creating the investments immediately. This decade will be the turning point and we must ensure that the turn is towards a sustainable, equitable future.

The author is AVP and Head of Environmental Sustainability– Godrej Industries Limited and Associate Companies

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article above are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of this publishing house. Unless otherwise noted, the author is writing in his/her personal capacity. They are not intended and should not be thought to represent official ideas, attitudes, or policies of any agency or institution.