India’s Green Transition Leaves Women Trapped In Low-paid, Informal Roles: CEEW

Despite evidence that gender diversity boosts productivity, women in India’s green value chains remain concentrated in low-wage, labour-intensive and informal work, a new analysis warns

A Report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) argues that India’s green economy cannot reach its full potential without women at the centre of the transition. The report underlines a clear economic payoff from higher female participation. It estimates that in the Asia-Pacific region, raising women’s share in the workforce could lift annual GDP by USD 4.5 trillion (INR 391.5 lakh crore) in 2025, a 12 per cent increase over current trends. For India, the study links the goal of a USD 30 trillion (INR 2,610 lakh crore) economy by 2047 to the creation of a 400 million-strong female workforce.

Despite this, India’s female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) remains low at 41.7 per cent, compared to the male LFPR of 78.8 per cent. The situation is stronger in urban areas, where women’s LFPR is just 28 per cent. Women are also underrepresented in leadership, holding only 18.3 per cent of senior roles in 2023, and a little over 10 per cent of key managerial personnel positions. Wage disparities are equally sharp, with salaried men earning around 30 per cent more than salaried women, male daily wage workers earning 50 per cent more, and self-employed men earning about 190 per cent more than self-employed women.

Productivity Gains, But Women Pushed To The Margins

The report cites evidence that enhanced women’s participation in a sector significantly boosts productivity. In India’s formal manufacturing sector, a 1 per cent increase in gender diversity in the workforce is associated with a 2.9 per cent rise in labour productivity and a 2.7 per cent boost in total factor productivity, suggesting that greater female inclusion could markedly enhance manufacturing output.

Yet, across green value chains, women’s work is characterised by low participation relative to men, concentration in non-technical and low-value segments, and persistent informality. In the energy transition sector, a survey by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) shows women constitute 32 per cent of the global renewable energy workforce, compared to 22 per cent in oil and gas, but they occupy 45 per cent of administrative positions and only 28 per cent of STEM jobs in technical, managerial and policy-making roles. A survey of nine rooftop solar companies in India revealed that women make up only 11 per cent of the workforce, with just 3 per cent and 1 per cent in construction and commissioning, and operations and maintenance, respectively.

Women Trapped At Bottom

In the circular economy, women are clustered in the earliest and lowest-paid stages of value chains as waste-pickers and segregators. Estimates suggest that 1.5 million women work as waste-pickers in India, making up 49 per cent of the sector, yet earning 33 per cent less than men in the same job. Many come from marginalised Dalit and Adivasi communities and face hazardous working conditions, systemic exploitation and caste-based stigma. While women collect and sort waste, men dominate better-compensated roles in aggregation, processing and selling, and women workers mostly remain informal and outside labour regulations.

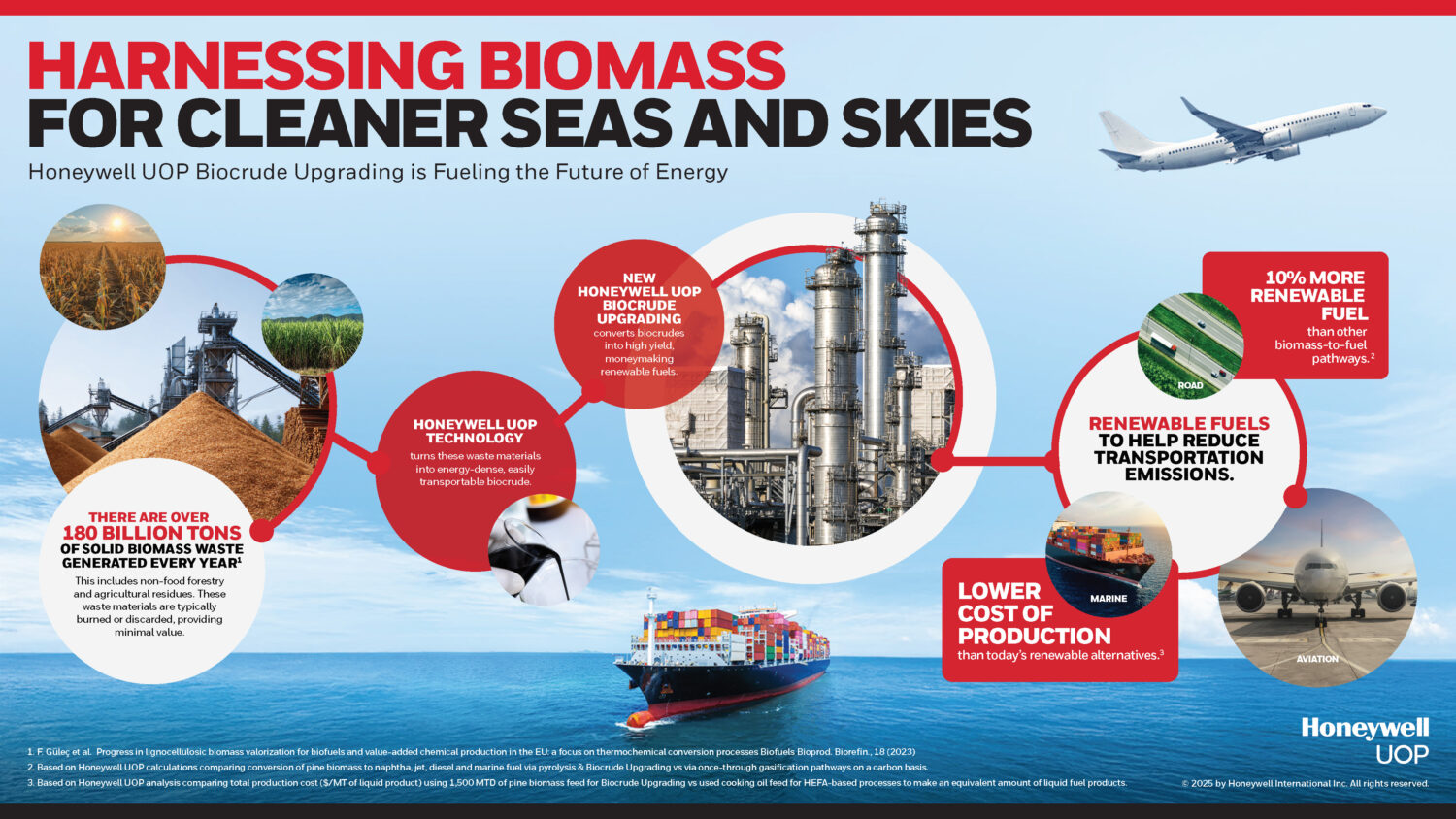

In the bioeconomy and nature-based solutions sector, most women work in informal, repetitive, labour-intensive roles such as collection of raw materials, input production and plantation activities in value chains like seaweed cultivation, agroforestry and sustainable forest management. Their work is often treated as unpaid, socially reproductive labour. Women in biofuels collect agri-residue and fuelwood, covering long distances and carrying heavy loads, while men dominate post-production processing in factories and manufacturing plants.

Across these sectors, socio-cultural barriers, lack of secure land tenure, limited access to finance, digital exclusion and non-conducive working conditions confine women to the least productive links of green value chains, even as India seeks to build a green economy for “Viksit Bharat”.