Reviving Rural Prosperity: Government’s Role In Driving Agri Innovations

Progress is visible, but the rate of adoption varies. Some regions have rapidly embraced new practices, while others lag due to lack of awareness, infrastructure, or funds

Byline: M.K. Dhanuka, Chairman, Dhanuka Agritech

Agriculture has been the backbone of India’s economy, sustaining nearly half of its population and making a major contribution towards national development. Yet, the sector is facing structural issues such as fragmented land holdings, monsoon dependence, post-harvest losses, and low productivity. These chronic gaps, further aggravated by weak market linkages and climate uncertainties, endanger the livelihoods of millions of farmers. India’s agricultural sector requires a bold infusion of innovation, technology, and policy intervention. The government has a key role to play in driving this change.

Even with the dramatic progress, rural India still struggles with deeply embedded constraints. Farmers face rising input costs and falling profitability, with erratic rainfall and falling groundwater adding to shrinking yields. The crisis is worsen by post-harvest inefficiencies, with almost 15–20 per cent of fruits and vegetables lost every year due to lack of storage, inefficient cold chains, and lack of processing units. Access to quality seed, modern equipment, and timely credit continues to be unevenly distributed, especially to smallholders, who form over 85 per cent of India’s farming community. Their modest ability to invest in mechanisation or high-yielding varieties, along with middleman exploitations and market volatilities, traps them in a debt and distress cycle. Unless agriculture becomes both profitable and sustainable, it cannot truly power rural prosperity.

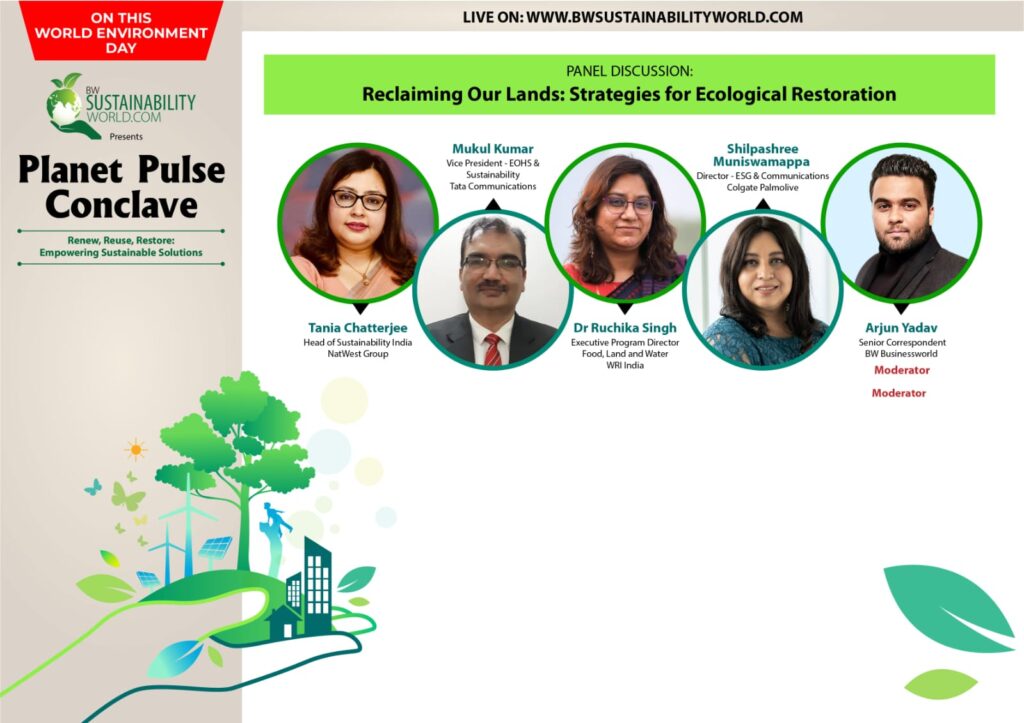

Government Interventions and New Frameworks

The government has rolled out a series of measures to strengnthen all the segments of the agriculture value chain. The Beej Se Bazaar Tak program brings the farmer to a chain of quality seeds, available credit, new technology, and market linkage, a turn towards integrated solutions. Likewise, the Navaratna approach encourages public sector units to invest in rural infrastructure and technology upgradation, public-private partnerships are bridging the gap between labs and fields. and the Kisan Vikas Yojana focuses on farmer-driven growth through diversification, institutional credit, and technology dissemination.

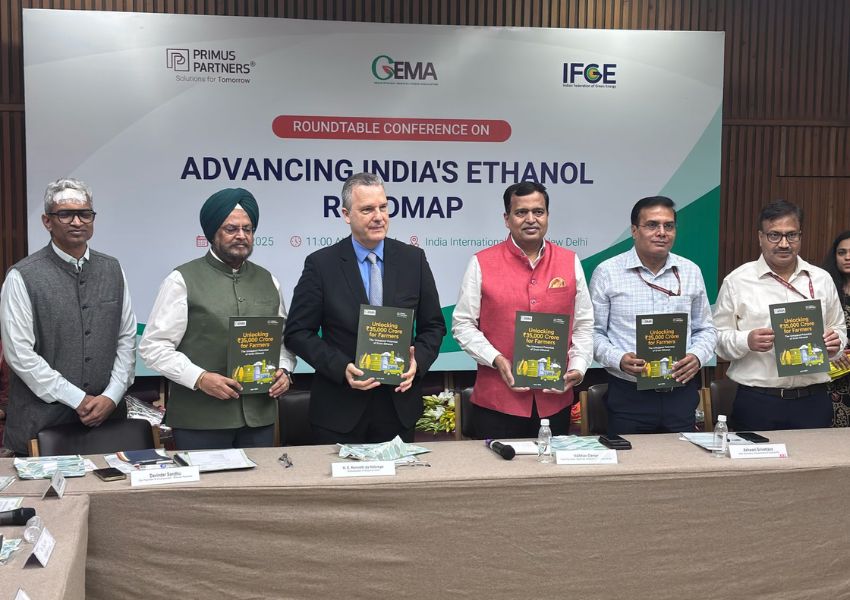

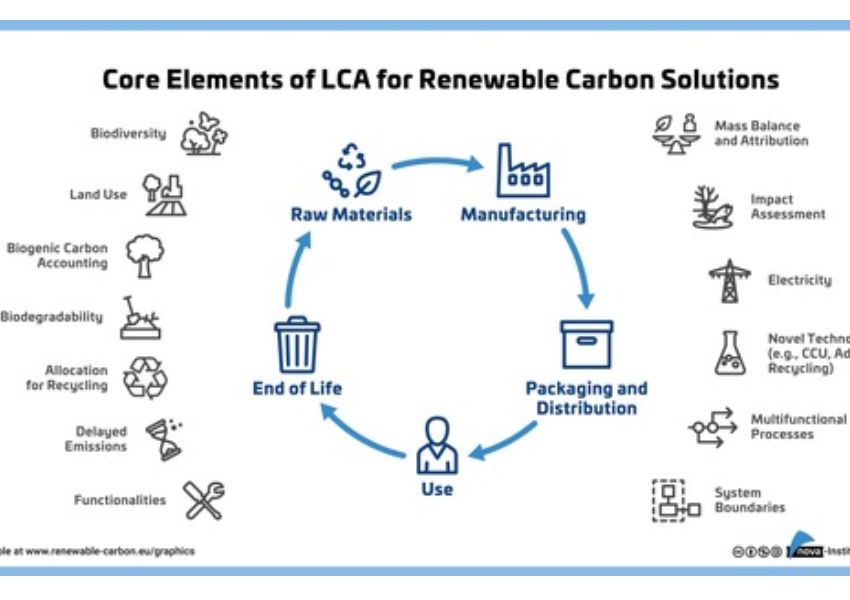

Apart from these, core programs have also encouraged innovation and sustainability. Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana offers incentives to go organic and implement eco-friendly practices, whereas the National Mission on Edible Oils – Oil Palm aims to reduce imports and increase local production of oilseeds. The Digital Agriculture Mission has started using artificial intelligence, IoT, and remote sensing in agriculture, making farming smart and data-driven. Infrastructure problems are being tackled through the Agri-Infra Fund, which helps in

warehousing, cold storage, and processing facilities, whereas income transfers under PM-Kisan Samman Nidhi help financially for farmers. These, in total, indicate the government’s desire to make agriculture robust, technology-enabled, and future-proof.

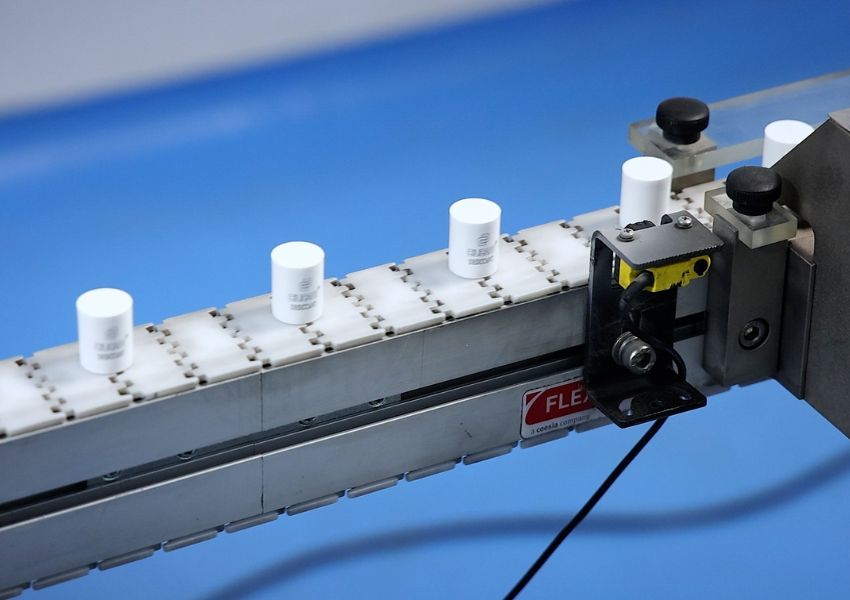

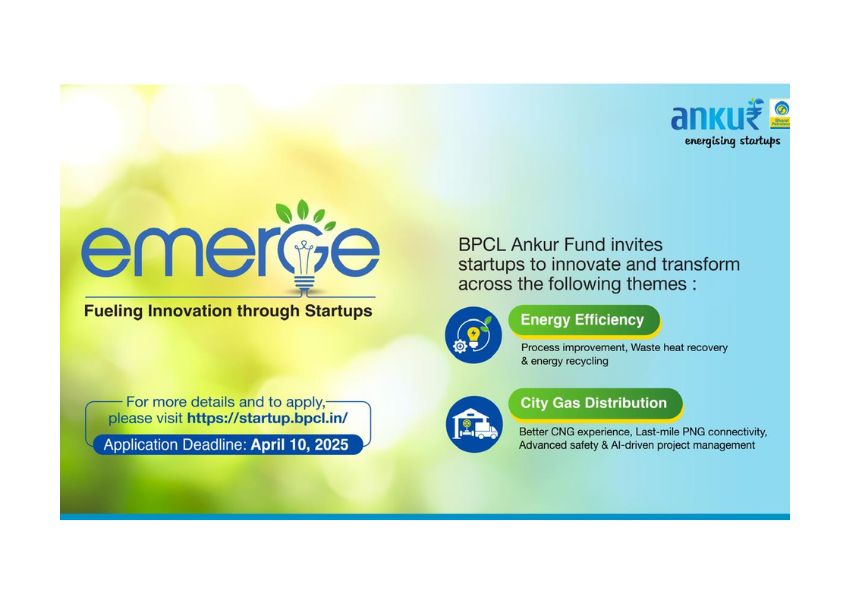

In terms of Technology Goverment has launched, the Drone Didi Yojana for rural women with drones to assist with precision spraying and crop monitoring. Soil health cards, satellite crop inspections, and digital platforms such as e-NAM are making farming more efficient, transparent, and better at discovering prices. Agro-startups, frequently assisted by the government, are inventing new solutions in bio-fertilisers, smart irrigation, hydroponics, and agri-fintech, while public-private partnerships are bridging the gap between labs and fields. These moves indicate a significant shift towards making Indian agriculture more modern and attractive.

The Need For Deeper Reforms

Progress is visible, but the rate of adoption varies. Some regions have rapidly embraced new practices, while others lag due to lack of awareness, infrastructure, or funds. To ensure all farmers gain, India must enhance its reforms and create a sustainable plan that provides instant relief and sustainable change.

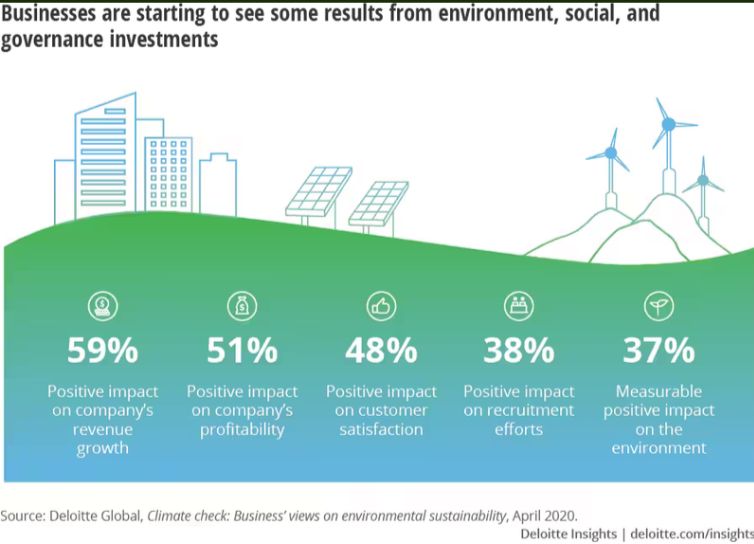

One of the largest requirements is additional funds for farm research and development. India only invests 0.06% of its GDP in agri-R&D, whereas others like China and Brazil invest nearly 1 per cent. Getting it to at least 1 per cent would result in incredible progress on crops that can adapt with climate change, improved means to defend crops, and more efficient use of resources. Improved public-private partnerships would accelerate new concepts and turn research into actual outcomes on farms.

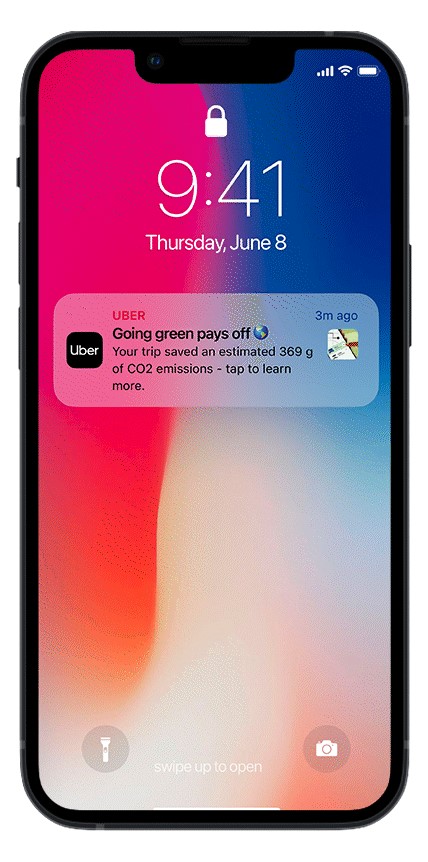

Policy reforms are necessary. High input cost coupled with the 18% GST on equipment, drones, and farm chemicals, makes it difficult to adopt new technology. Lowering GST will reduce the price of new equipment, particularly for small farmers. Outdated laws, such as the Insecticides Act, hinder progress by taking an eternity to approve safer and better alternatives. Strengthening market connections is another important goal. e-NAM has set up an electronic platform for open trading, but it does not reach the masses. Adding more crops to the platform and linking it directly with the local markets would create a real national marketplace. Supporting farmer groups with digital platforms, credit, and market information would enable small farmers to negotiate more, lessening their reliance on intermediaries and allowing them to get a fairer share of what consumers pay.

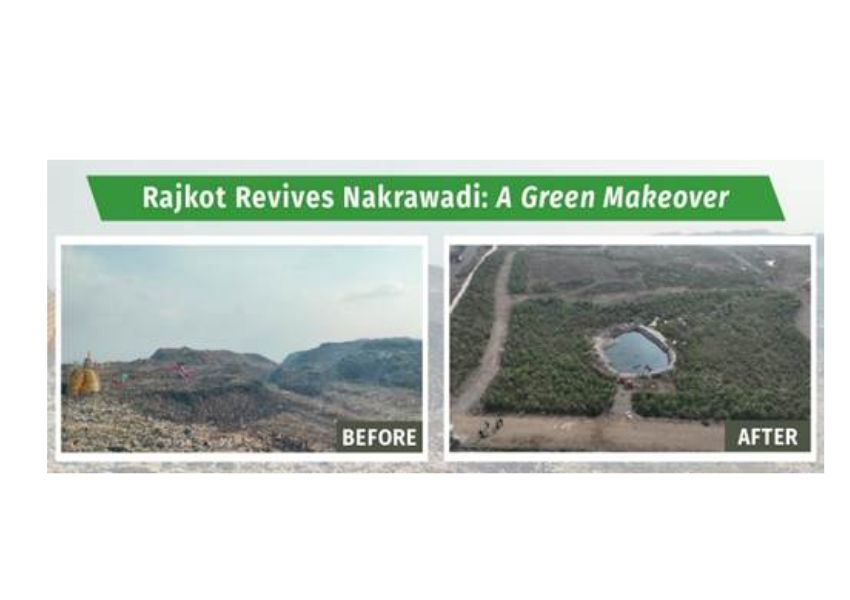

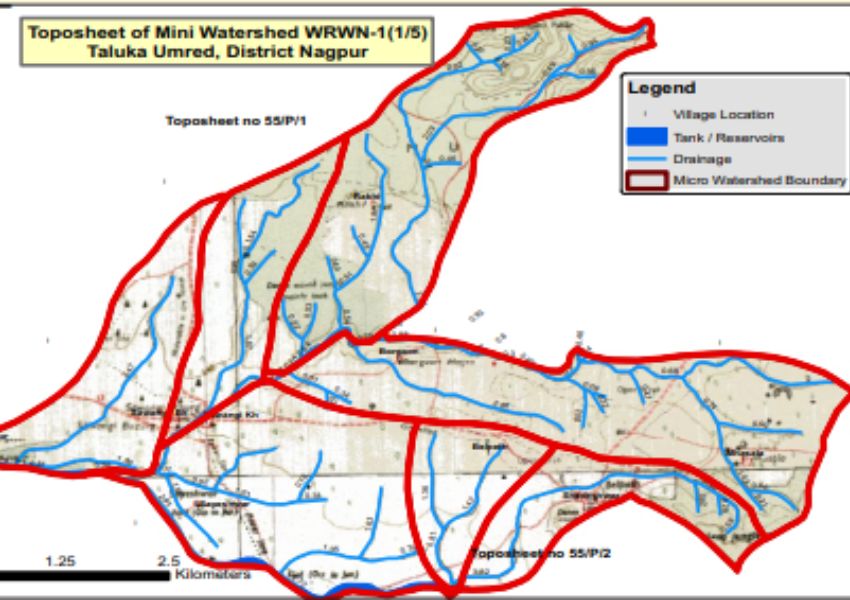

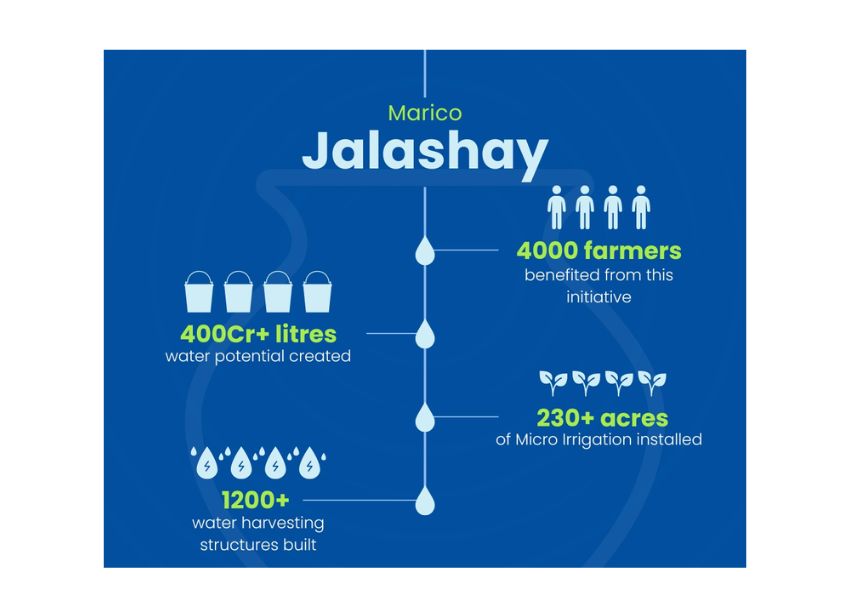

The future of Indian agriculture is also dependent upon water-saving agriculture. With rainfall becoming increasingly unpredictable and groundwater being further depleted, policies need to give topmost priority to micro-irrigation, watershed management, and rainwater harvesting. Encouraging drought-tolerant and lower water-thirsty crops would decrease exposure to climate shock and stabilise farm incomes. Water shortage can undo three decades of rural prosperity if prompt action is not initiated.

Structural incentives such as a Production Linked Incentive scheme for farm technologies, bio-inputs, and agrochemicals would also drive change. Just as PLI schemes have brought back electronics and pharma, the same template in agriculture would create domestic capability, lower import dependence, and cost of cutting-edge technology. Apart from improving productivity, such schemes would create rural jobs and facilitate the dream of an Atmanirbhar Bharat.

Towards Viksit Bharat 2047

As India progresses towards Viksit Bharat by 2047, agriculture needs to evolve from subsistence to enterprise. Subsidisation is not the government’s job alone; it needs to build an ecosystem that is innovative, competitive, and sustainable. By developing strength in Beej Se Bazaar Tak, R&D investment, modernisation of regulation, and inclusive growth, India can empower its farmers to lead the country towards prosperity and climate resilience.

The foundations have been established with far-sighted programs and aggressive policies, but the real test of achievement will be in implementation and participation. Rural prosperity will not be the result of piecemeal initiatives but will be the result of one, innovation-driven approach that harmonises technology, policy, and farmer participation. If this mission is taken up with urgency and commitment, agriculture can become the bedrock of India’s economic and social transformation once again renewing not only rural prosperity but also the overall progress of the country.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.