Steel’s Carbon Curve: India At A Trade Crossroads

Transition bottlenecks and EU’s carbon border tax raise costs for Indian producers, yet global demand for green steel offers a growth window

India’s steel sector is approaching a critical inflection point as domestic demand for “green steel” is forecast to rise to around 179 million tonne by FY50, but exporters face an immediate challenge: a widening emissions gap with the European Union (EU) that could result in hefty levies under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This forces a rethink of export strategy, investments, and policy support.

Indian crude steel currently carries an emissions intensity of roughly 2.5 tCO₂ per tonne, compared with the EU benchmark of 1.28 tCO₂ — a gap of about 106 per cent. According to EY Parthenon, that differential, combined with tightening EU benchmarks and the phased withdrawal of free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System, could expose Indian exporters to CBAM costs amounting to Rs 19,277 crore by 2030.

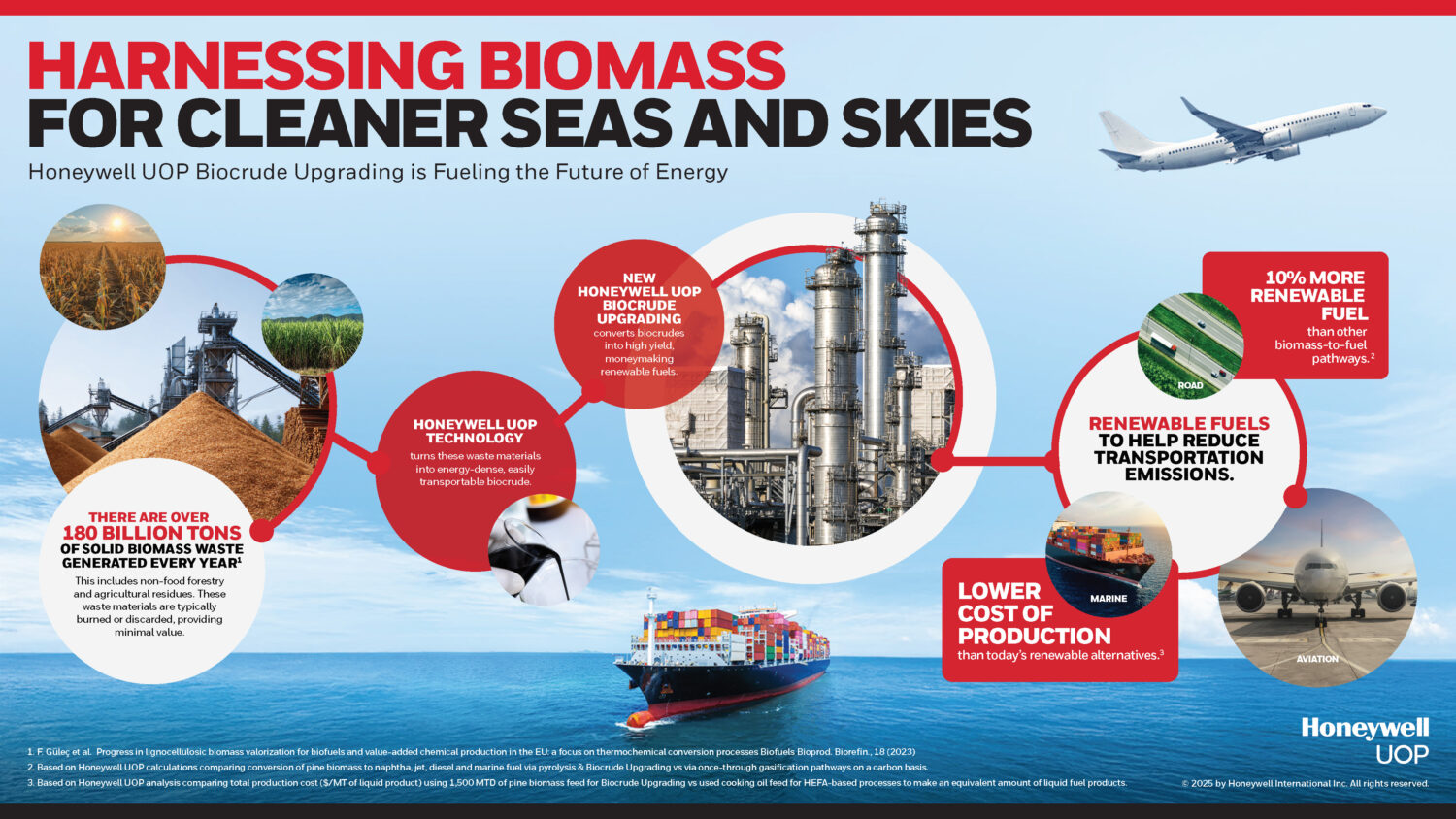

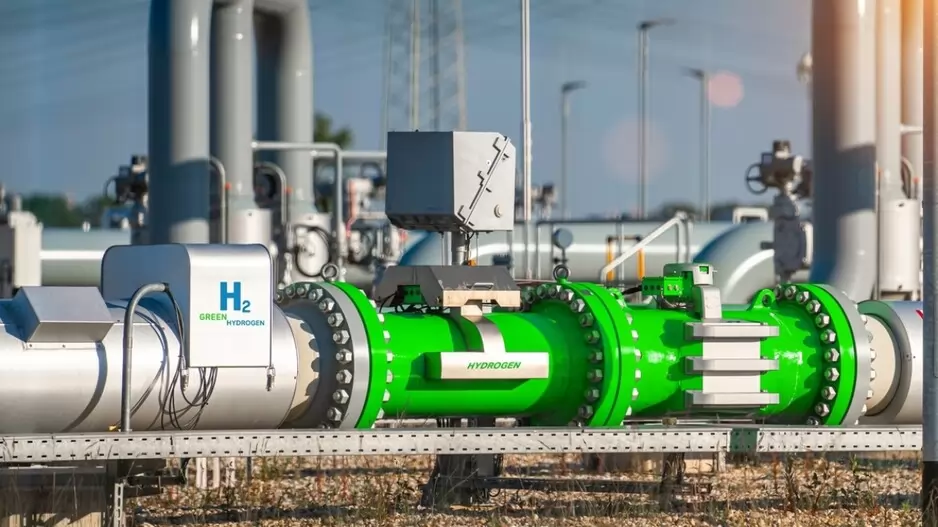

The report estimates that CBAM’s cost burden could rise from about USD 1,009 million in 2026 to nearly USD 2,400 million by 2030, before climbing to an estimated USD 14,500 million by 2050 if current practices continue. EY Parthenon emphasises that Indian steelmakers need urgent decarbonisation efforts — such as improving energy efficiency, integrating renewables, piloting carbon capture, and preparing for green hydrogen and scrap-based steelmaking — to contain risks.

Costs, Competitiveness And The Buyer Response

For EU importers, CBAM will mean higher steel prices, especially in construction, automobiles, and infrastructure. Estimates suggest that Indian steel exports may face additional costs of USD 55-65 per tonne between 2026–29, rising to USD 90–145 per tonne in 2030–34.

Industry bodies such as the Indian Chamber of Commerce (ICC) have noted that higher carbon intensity makes Indian steel less competitive in the EU, putting pressure on exporters.

Rajeev Singh, Director General – ICC, said, “Given the higher carbon intensity of Indian steel production, exporters may face significant cost pressures, impacting their competitiveness in the EU market as importers will be required to purchase CBAM certificates reflecting the carbon price under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). Estimates indicate a potential duty of €173.8 per tonne-around 16.06 per cent of the unit value in 2022. Indian steel exports could incur additional costs of USD 55-65 per metric tonne (MT) during 2026–2029, rising sharply to USD 90-145 per MT between 2030 and 2034.”

Larger integrated players with operations in Europe, and therefore already covered by the EU ETS, may find compliance easier, but small and medium-sized producers face significant capacity constraints. Singh added, “Big companies may be able to meet the EU demands through local operations. MSME Steel makers need Government support in getting access to renewable Energy, steel Scrap, hydrogen based DRI and affordable finance.”

A large portion of India’s steelmaking capacity continues to depend on blast furnace–basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) routes and coal-based direct reduced iron (DRI) systems, making the transition to cleaner processes particularly challenging. Scaling hydrogen-based DRI, for instance, hinges on the availability of reliable green hydrogen, while greater use of electric arc furnaces (EAFs) requires access to quality scrap, which remains limited in India. Even when producers shift to electric-based routes, the decarbonisation benefits are reduced unless renewable energy is integrated, given that the national grid is still heavily coal-dependent. Adding to these hurdles are gaps in emissions data: CBAM compliance demands product-level, auditable reporting, but fragmented supply chains and manual data collection make monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) especially difficult for smaller players.

The Finance Puzzle: Who Pays For Green Steel?

The transition comes with heavy capital requirements. Green hydrogen-based DRI, CCUS, EAF conversions and retrofits are all expensive. High costs and limited access to affordable finance have been highlighted as major hurdles, especially for smaller firms.

Kapil Bansal, Partner – Energy Transition and Decarbonisation, EY Parthenon, “The high cost of green hydrogen currently renders GH2-based DRI steelmaking commercially unviable. Moreover, the capital expenditure required for setting up new low-emission facilities or retrofitting existing ones is significantly high, posing a barrier especially for smaller players.”

Analysts argued that without mechanisms such as green transition funds, tax incentives, or carbon contracts-for-difference, adoption of low-carbon technologies will remain limited.

Policy Moves And Market Response

Experts believed that India’s regulatory landscape is evolving, but gaps remain. Many Indian steel exporters—particularly Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)- face significant capacity constraints in meeting the stringent data requirements mandated by the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) from January 2026. The lack of technical and financial resources for detailed, production-level emissions tracking presents a substantial compliance challenge. India’s steel sector is further hindered by fragmented supply chains, manual data collection practices, and the absence of EU-aligned monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols. The limited availability of accredited third-party verification mechanisms increases the likelihood of default emissions values being applied, thereby escalating carbon costs under CBAM. Additionally, the lack of a standardized, product-level MRV framework at the national level has led to inconsistent data quality and availability on embedded emissions, weakening the credibility of export declarations and potentially undermining market access