Storing Tomorrow’s Power: Is India Ready For 24×7 Renewables?

Even if the manufacturing puzzle is solved, India’s power sector laws and regulations can prove a formidable labyrinth

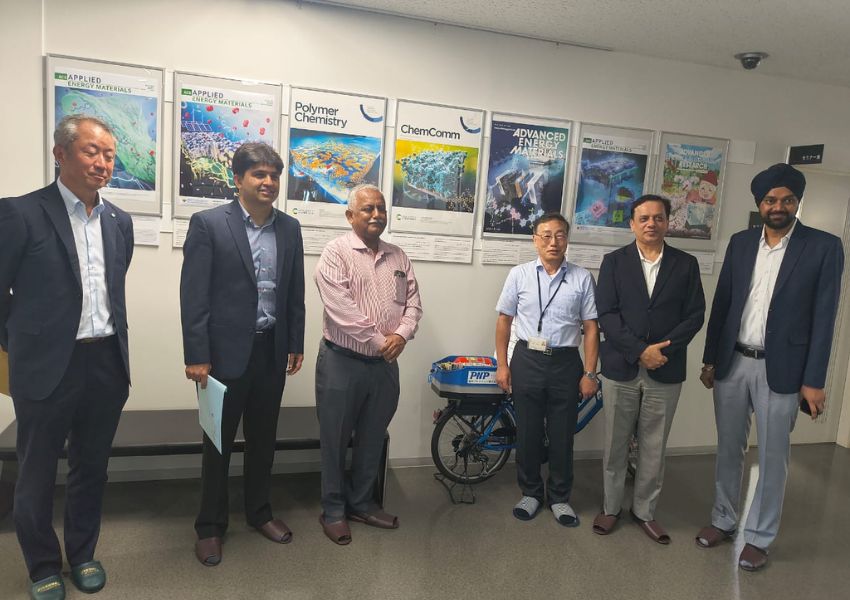

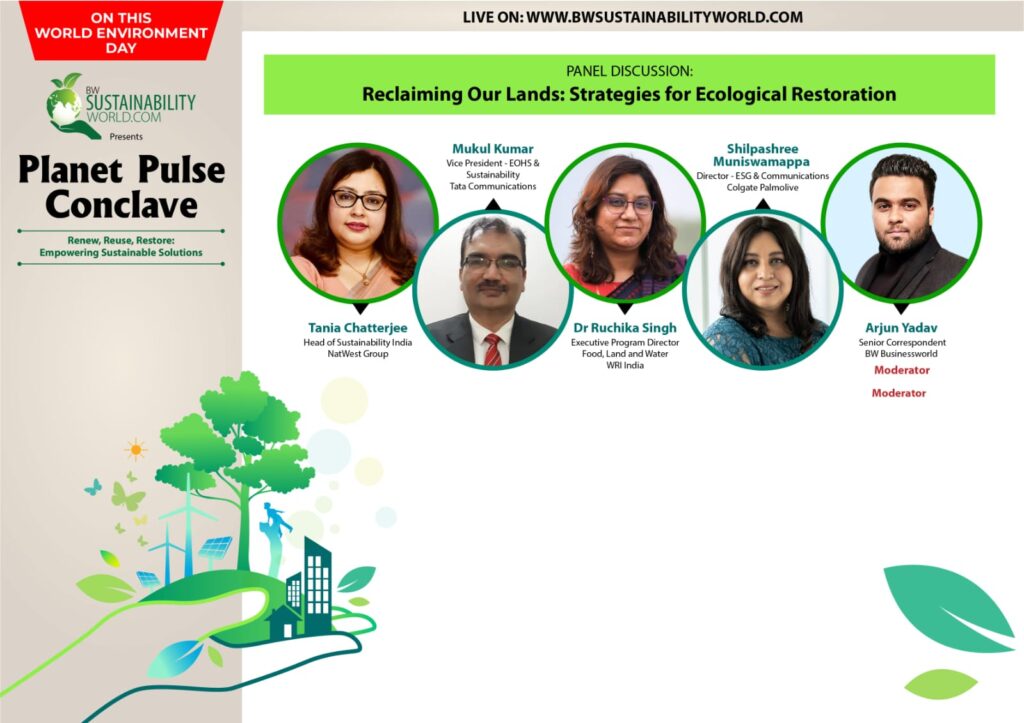

Byline: Vivek Agarwal, Global Policy Expert, Country Director, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

India’s renewables have indeed come a long way, giving the world reason to believe that a future of clean, abundant electricity may not be as elusive as once feared. But solar and wind projects remain beholden to fluctuating weather and daylight conditions, raising the perennial question of how to preserve all those green electrons until they are needed. Batteries emerge as the critical missing link. Their potential is so vast – ensuring grid stability, powering remote villages, lowering import bills – that one cannot help but wonder if we are truly prepared to seize this transformative technology. The answer demands an unflinching look at the obstacles we face, opportunities in our path, and a strategy that ensures these innovations move from pilots to nation-wide projects.

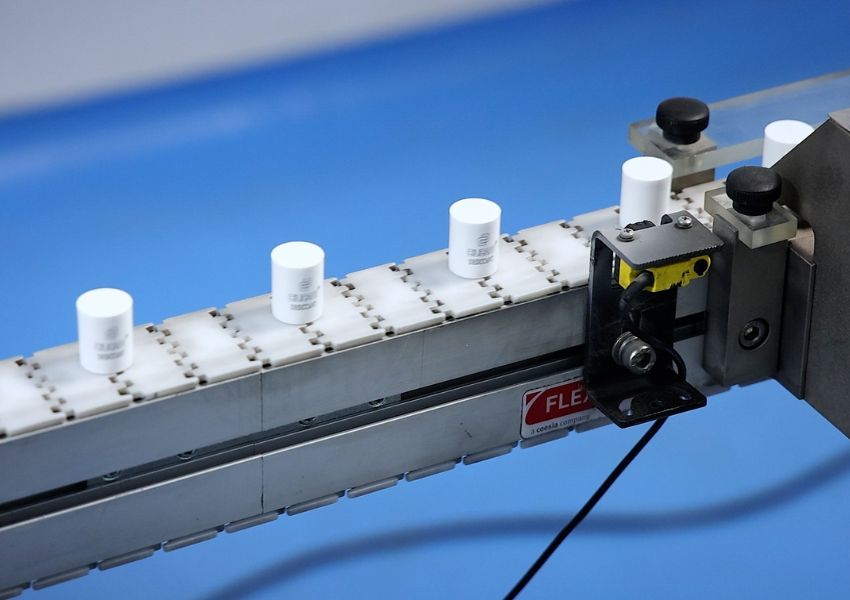

India’s ability to manufacture batteries at scale is nascent. Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme has attracted major players like Reliance, Tata, and Ola Electric to set up giga-factories, creating a local supply chain for lithium, cobalt, nickel. However, advanced cell components require more than just large plants. Realizing that ‘Made in India’ batteries will reduce currency risks and import dependence, policymakers are trying to kickstart local refining, forging overseas partnerships for resources, and even exploring fresh lithium finds in Jammu & Kashmir. Yet that deposit remains in the ‘inferred’ category, possibly years away from commercial mining.

Even if the manufacturing puzzle is solved, India’s power sector laws and regulations can prove a formidable labyrinth. A battery, after all, must be integrated into the grid. Is it a generation? Is it distribution infrastructure? Is it both, or something else entirely? Such ambiguities can trigger double charges, project delays, or simply spook potential investors. Some states have introduced new approaches such as utility procurements that treat batteries as capacity resources, but a consistent national framework is much needed. Investors crave regulatory stability. Absent that, they may be reluctant to put money into large battery projects.

Cost and financing also loom large, partly because banks, still hesitant with technology that defies neat classification, fear uncertain revenue streams. One might witness a project promising value from peak shaving, frequency control, or capacity payments. However, India has only recently begun to create robust ancillary markets that compensate for such services. Bundling storage into hybrid solar/wind power purchase agreements can spread costs. Storage-as-a-service, where a third party owns the battery and charges a user fee, might circumvent hefty upfront capital. But these new business models, while inventive, are still fresh experiments.

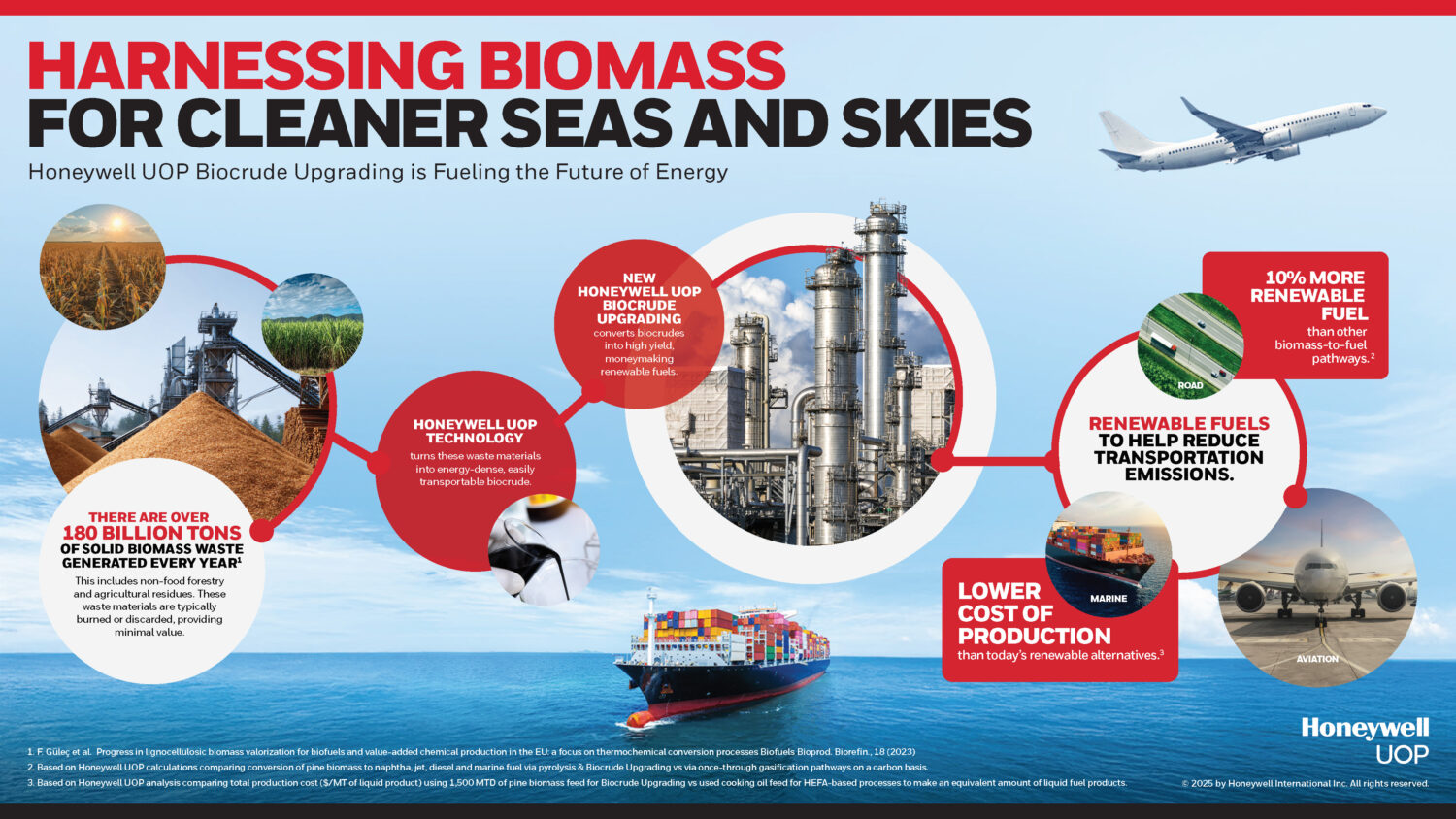

None of these concerns should eclipse the environmental complexities. While storing clean energy on a mass scale seems beneficial, battery production and disposal themselves can harm ecosystems if poorly managed. Mining for lithium or cobalt can devastate landscapes and communities if corners are cut. If we fail to establish high-quality recycling in parallel with manufacturing, piles of used lithium-ion cells may eventually create a secondary pollution crisis. Incidents of thermal runaway, though rare, highlight the crucial need for robust fire codes and emergency response training. And let us not ignore the energy footprint of battery production itself: if these giga-factories run on coal-heavy grids, their embedded carbon footprints can undercut some of the climate benefits they promise.

All said, none of these stumbling blocks are insurmountable. Case studies both at home and overseas highlight pathways and spark optimism that these hurdles can be conquered. In Rohini, Delhi, for instance, Tata Power, AES, and other collaborators installed a relatively modest 10 MW lithium-ion system that demonstrated how a big urban distribution utility can level out demand spikes, improve frequency regulation, and offer backup power in emergencies. Even that small-scale success reassured regulators that the technology is viable and more such batteries have followed in other states.

In Andaman & Nicobar, a 20 MW solar facility plus 8 MWh of storage replaced swaths of diesel generation. The project overcame supply chain delays, topographical challenges, and variable weather conditions, enabling a more stable, low-carbon power supply to island communities that had been wrestling with the cost and insecurity of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, Australia’s Hornsdale Power Reserve, though on a different continent, has become a global landmark for how swiftly a 100 MW/129 MWh battery can respond to grid emergencies, lower electricity costs, and earn stable revenues through ancillary markets. Germany, too, offers lessons, where residential rooftop solar joined with small home batteries can scale up to the millions, forming a virtual power plant that eases grid stress and encourages self-sufficiency.

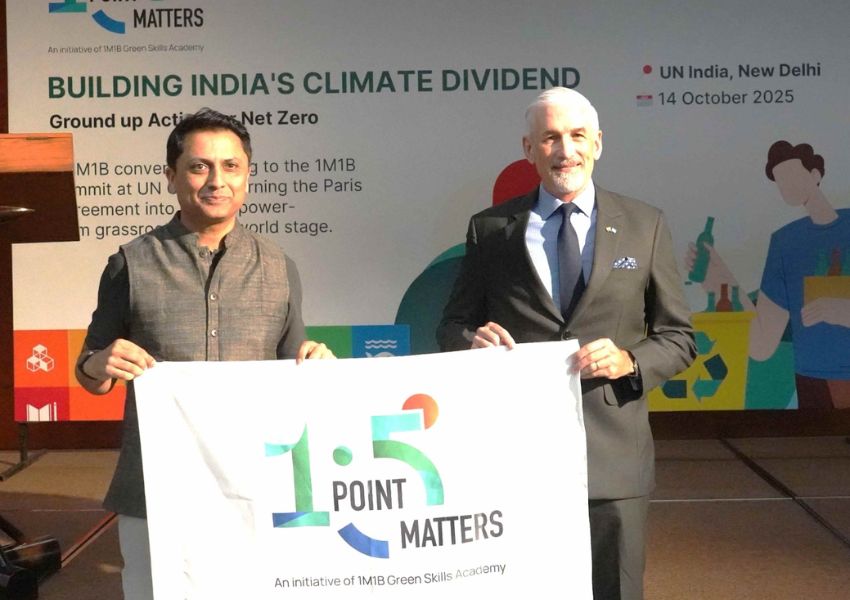

These achievements are not merely about technology but also of successful institutional design – providing India a path to emulate. Manufacturing impetus can be sustained by healthy policy frameworks, so we should fortify our battery supply chain by aggressively promoting domestic refining, encouraging recycling through legally binding take-back obligations, and forging agreements with resource-rich nations. Market reforms should classify storage as a distinct asset, remove double charges, and actively compensate ancillary services to ensure that project developers see a clear path to profit. Financing innovation is also imperative: more hybrid “solar-plus-storage” auctions, more creative revenue contracts, and the embrace of third-party ownership models might tip the scales. And while we do all of this, environmental guardrails need to be robust – stringent recycling targets, mandatory safety standards, and incentives for factories that source renewable energy will lessen the potential downsides.

The question, of course, is whether we as a nation will muster the resolve and coordination to make all of this happen. It sounds ambitious, some might even say idealistic, but we saw how India scaled up solar in less than a decade. Could the battery revolution emulate solar’s exponential leap? Many experts argue that the blueprint is already in place: a combination of strategic subsidies, strong local manufacturing alliances, well-designed bidding processes, and the unstoppable momentum of global battery price declines. If we succeed, the diesel generator’s relentless hum may soon become an echo of the past replaced by the quiet hum of batteries storing the sun for India’s bright tomorrow.