Coal-dependent India Battles Complex Supply Chain Emissions Crisis

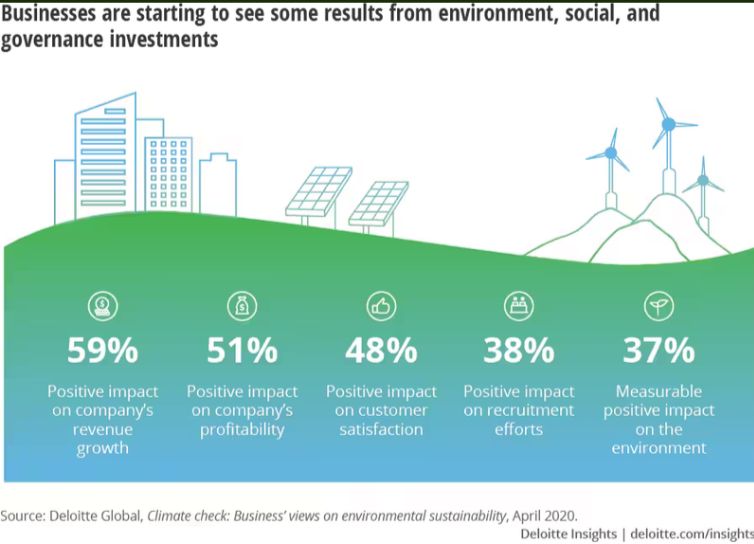

Scope 3 emissions – those indirectly associated with a company’s value chain – can constitute up to 70 per cent of a company’s total greenhouse gas emissions

As India’s economy continues to expand, projected to become the world’s third-largest by 2028, its responsibility toward global environmental well-being intensifies. The escalating impacts of the climate crisis are evident daily, manifesting as extreme weather events, environmental degradation, and their profound effects on communities. In this context, the ambitious goal set by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070 underscores the urgency and sincerity required in our collective climate action efforts.

Scope 3 emissions – those indirectly associated with a company’s value chain – can constitute up to 70 per cent of a company’s total greenhouse gas emissions. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2024 report, only about 31 per cent of Indian companies reporting emissions to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) include scope 3 data, and a mere 22 per cent of those have targets aligned with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). This gap highlights a disconnect between ambition and action, especially since Scope 3 emissions often represent the largest portion of a company’s total carbon footprint.

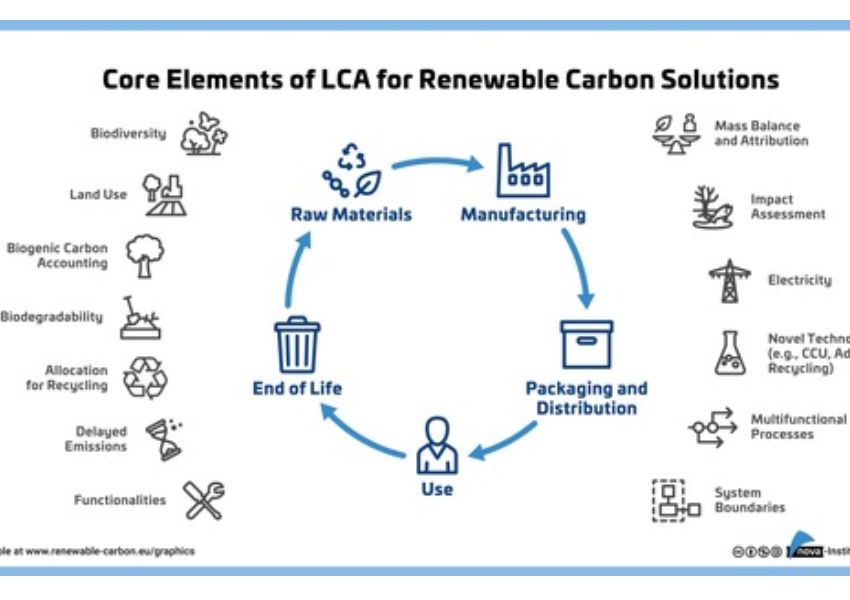

India’s value chains, which span a wide spectrum of large enterprises, MSMEs, and SMEs, are inherently complex and fragmented – posing considerable challenges for accurately measuring and managing scope 3 emissions. While reporting on direct (scope 1) and energy-related (scope 2) emissions has improved across sectors, scope 3 disclosures remain limited due to systemic issues. Many smaller firms lack the technical capacity, financial resources, and awareness needed for robust carbon accounting. As a result, the quality and reliability of upstream and downstream emissions data are often compromised. Further complicating matters is the absence of standardised reporting frameworks and the frequent reliance on generalized industry data, which can obscure the true emissions footprint. In some cases, organizations set net zero targets that exclude scope 3 emissions entirely, undermining the credibility and environmental integrity of their commitments. Strengthening scope 3 accounting practices is therefore essential if India is to make meaningful progress toward its national decarbonisation and net zero goals.

Despite promising data and increasing momentum, India faces significant structural and systemic challenges in advancing Scope 3 emissions measurement and reduction, particularly across its vast base of SMEs and MSMEs. A staggering 88 per cent of MSMEs lack the technical knowledge to implement sustainability strategies, and for 81 per cent, capital constraints further hinder the adoption of essential infrastructure. Outdated and inefficient operational systems, coupled with limited digitization, make carbon tracking both financially and operationally burdensome. This technological lag is also reflected in India’s 2021 Biennial Update Report, which points to the sector’s persistently high energy intensity – largely driven by outdated technologies and informal practices – contributing to elevated indirect emissions across industrial supply chains. Adding to the complexity is India’s current energy mix: as of 2023, over 56 per cent of the country’s electricity comes from coal, with another 33 per cent from oil and gas, and only 10.48 per cent from renewables. This energy profile significantly slows progress on both scope 2 and scope 3 reductions, particularly for suppliers dependent on grid electricity. In the absence of faster deployment of renewable infrastructure, these indirect emissions will continue to flow through value chains, limiting the nation’s ability to make meaningful progress toward deep decarbonisation.

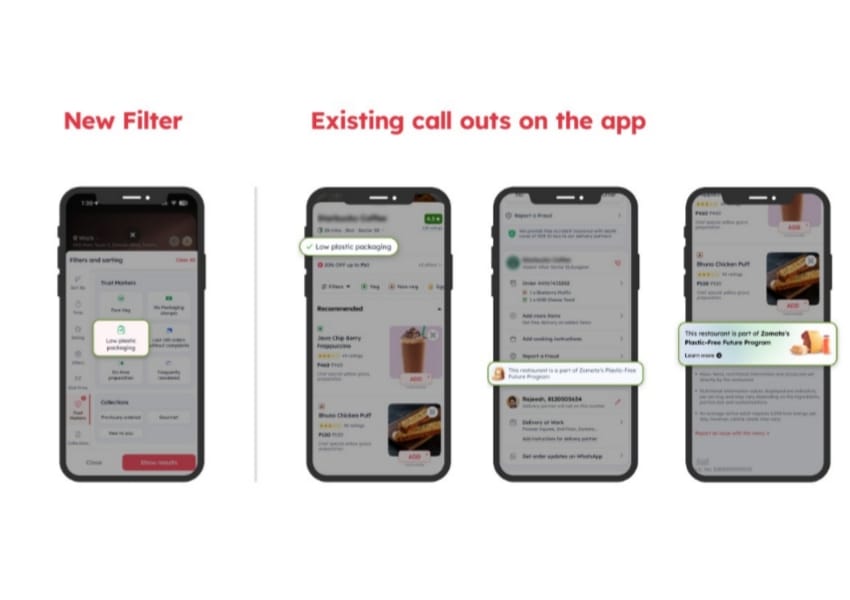

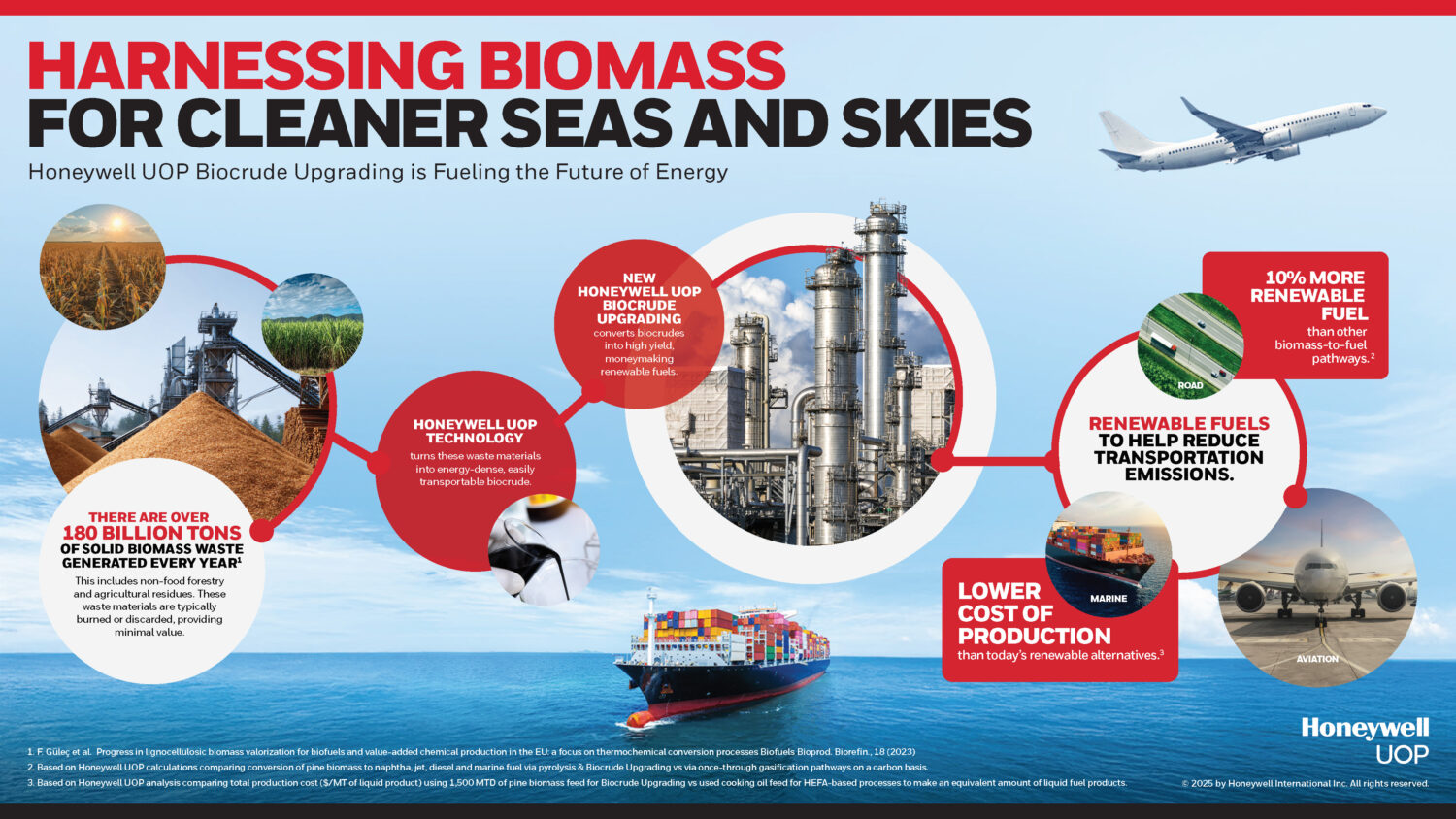

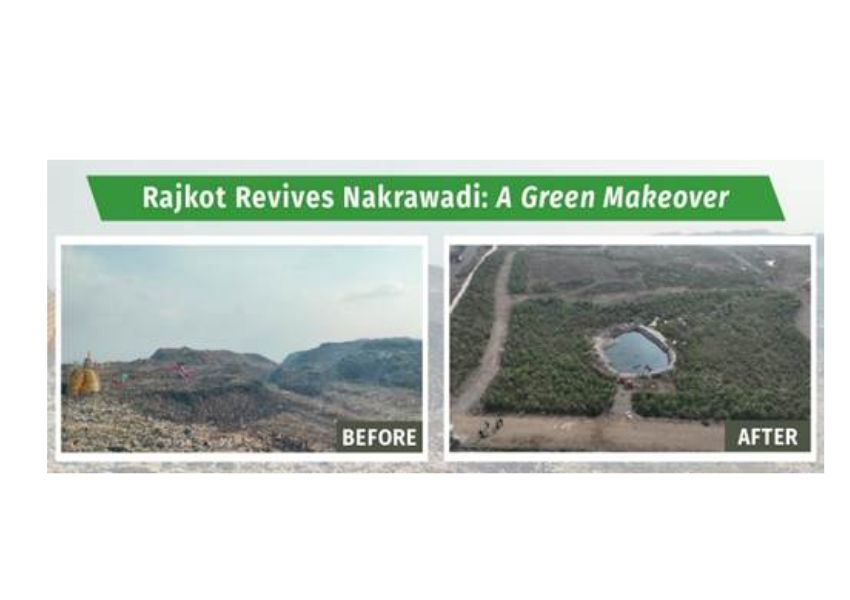

To accelerate scope 3 emissions reduction in India, a targeted and collaborative approach is essential. Establishing shared green infrastructure in industrial clusters – such as solar rooftops, biomass plants, and waste-to-energy units – can help MSMEs access low-carbon solutions without incurring high individual costs. Digital platforms, aligned with frameworks like the BRSR, should be developed to simplify emissions reporting through automated calculations, standardised formats, and sector-specific tools. Capacity-building efforts must be scaled up, with public-private partnerships offering technical training and mentorship to smaller enterprises. Addressing financial constraints is equally critical: a green finance framework should provide concessional loans, tax benefits, and innovation-linked grants. Finally, greening the grid – especially in tier 2 and tier 3 regions – requires upgraded transmission infrastructure, expanded renewable capacity, and greater deployment of battery energy storage systems (BESS). Complementary measures such as logistics electrification, electric industrial boilers, and green hydrogen adoption in key sectors can further cut indirect emissions and support grid stability.

The future is clear: unlocking the innovation, policy tools, and skilled workforce required for this transformation will necessitate a concerted effort among government regulators, business executives, and academic institutions. If given the right support, Indian industry at all levels and in all sectors has the potential to lead the way in developing a net-zero, low-carbon, climate-resilient economy by 2070.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the official policy or position of the publication or Grasim Industries.