The Missing Piece In Global Climate Policy: Frontline Leadership

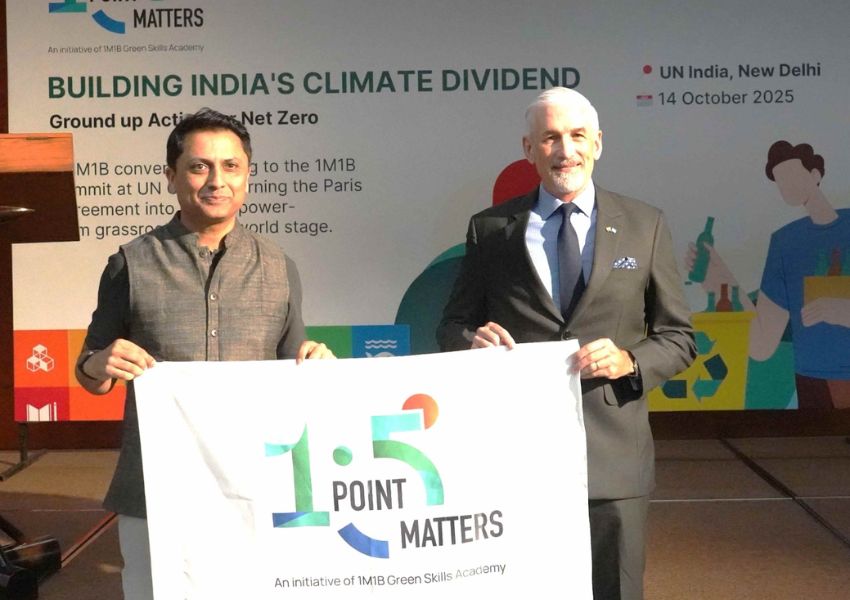

Byline: Manav Subodh (Founder, 1M 1B and Curator, 1.5 Matters)

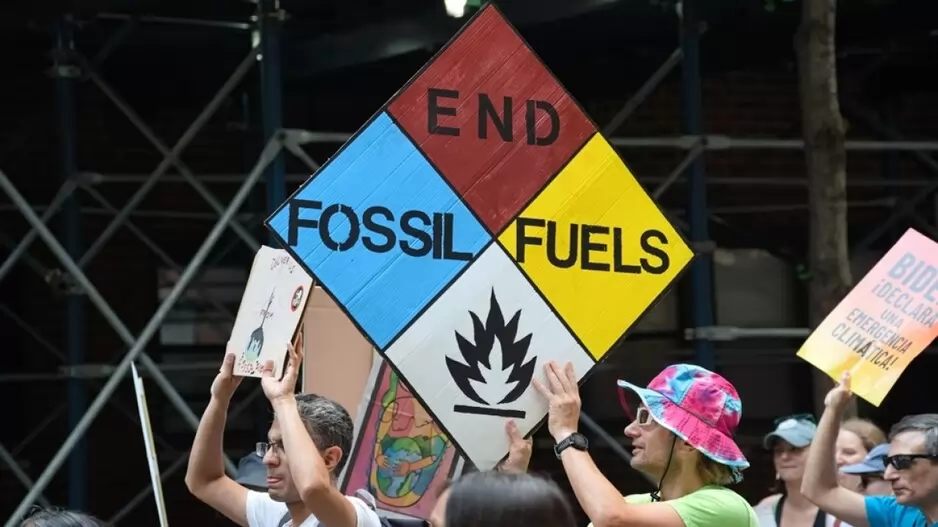

In the weeks leading up to COP30, thousands of Brazilians have taken to the streets across Belém, Manaus and several Amazonian municipalities. These demonstrations aren’t symbolic; they reflect a growing frustration from Indigenous and frontline communities who believe that global climate negotiations continue to overlook the people most at risk. Protest organisers have pointed to three specific concerns: continued land violations in the Amazon, insufficient financing for adaptation, and the exclusion of Indigenous voices from decisions that directly affect their land, food systems and water security.

This public pressure is not limited to Brazil. According to the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, climate-related disasters have increased five-fold over the last fifty years. The World Bank estimates that climate change could push more than 130 million people into poverty by 2030, with rural communities in developing nations facing the steepest losses. Yet, these communities account for a tiny fraction of historical emissions. This imbalance is what drives the protests we are now seeing. It is also the core reason COP30 must take climate justice seriously.

If COP30 is to be meaningful, it needs to respond to these demands with practical restructuring of climate action. That begins with recognising that frontline communities do not just experience climate change. They understand it earlier, they feel it more acutely, and they often know what works. Their knowledge and leadership must shape the next phase of climate action.

A Community-Led Approach Is Essential

Across India, early-warning systems, changes in soil behaviour, fishing patterns, heat exposure and water stress are detected first by local communities. Scientific assessments often confirm what these groups already know. A 2023 study by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research showed that farmers in semi-arid regions could predict crop stress nearly ten days before satellite indicators flagged risk. Similar findings apply to coastal communities. Fisherfolk in Tamil Nadu have reported shifts in fish stock movement that later aligned with ocean temperature anomalies identified by NOAA.

These insights matter because most climate impacts are hyperlocal. Global strategy cannot succeed unless it is grounded in local knowledge. Yet, only a small share of climate finance reaches the community level. The OECD estimates that less than ten percent of climate adaptation funding globally flows directly to local actors.

This mismatch creates slow, expensive, and often ineffective solutions. It also fuels resentment, which is now visible in protests not just in Brazil but in multiple climate-vulnerable regions. A more participatory, community-led model is no longer optional. It is necessary.

Building Climate Capacity Through Urban Rural Partnerships

India has an opportunity to develop a scalable model that links rural climate knowledge with urban skills, technology and networks.

This requires coordinated action across civil society, educational institutions, philanthropic organisations and companies. India is in the middle of its demographic dividend, with a young population that must be equipped to understand and act on climate challenges. To do this, climate exposure and community collaboration need to be built directly into the education and skilling system.

Urban CSR funding can serve as a practical connector. Today, many CSR efforts in environment and education remain urban-focused and disconnected from rural realities. Directing even a portion of these funds toward structured partnerships with rural schools and communities would allow technology, research capacity and institutional resources to meet frontline knowledge and local priorities.

Participation in multilateral platforms, whether at the UN or at climate summits, is often seen as a sign of leadership. But meaningful global engagement depends on domestic grounding. Representatives from any sector should have credible, on-the-ground understanding before speaking internationally. A national framework that encourages schools, colleges, civil society groups and companies to jointly implement climate projects with rural communities would help create that grounding and strengthen India’s voice globally.

These partnerships can build a pipeline of climate-aware workers, researchers and policymakers who understand both science and lived vulnerability. With India’s demographic window narrowing, integrating this approach into mainstream education and skilling is a strategic necessity, not an optional reform.

Youth Climate Diplomacy Needs Clear Pathways

Youth representation at global forums has increased, but the pathways to meaningful participation remain unclear. Many young delegates arrive at the UN with strong academic interest but limited exposure to the lived effects of climate change in rural and frontline communities.

A more effective model links international participation to domestic accountability. If a young person wants to represent India at a UN platform, they must first work with a rural partner school on a verifiable conservation or adaptation project. This approach creates discipline, encourages empathy and ensures that young delegates carry real community insights into global spaces. It also strengthens the credibility of youth representation on climate issues.

What COP30 Should Commit To

COP30 should respond to the concerns raised by Brazilian protesters with clear commitments that reflect urgent needs.

First, climate justice must be central to the agenda. This means recognizing that communities with the least responsibility for emissions are facing the earliest and most severe impacts. Their demands for protection and recognition must be considered as legitimate and should be included in the conversation accordingly.

Second, global climate finance mechanisms need restructuring so that funding reaches local actors faster and with fewer administrative barriers. Community-led projects often require small budgets but generate high resilience value. Large-scale consultant-driven designs cannot replace local ability and insight.

Third, COP30 should support structured global youth climate diplomacy programs that focus on training, negotiation skills, community work and grounded scientific understanding. Youth participation must be a serious responsibility, and not a ceremonial presence.

Conclusion

The protests in Brazil are not an isolated show of frustration. They are part of a broader signal from frontline communities across the world. The people who contribute least to climate change are carrying its heaviest burdens. Their requests are not unreasonable. They want genuine representation, protection of their land and the ability to shape solutions that affect their future.

If COP30 wants to be remembered as a turning point, it must take this message seriously. The summit must shift climate action toward models that are community-led, locally informed and supported by global systems of finance and diplomacy. The success of the next decade depends on whether the world recognises that frontline leadership is not an option. It is the only path that aligns climate action with justice, equity and long-term impact.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.