Trade Deals Used To Enforce Strict Seed Patents, Threatening Farmers’ Rights: Report

Report says that free trade agreements are reshaping global agriculture by enforcing restrictive seed patent laws, eroding farmers’ seed rights and concentrating control in corporate hands

A report by Grain has warned that powerful economies are increasingly using free trade agreements to impose restrictive intellectual property rules on seeds, undermining farmers’ rights and tightening corporate control over agriculture across the developing world.

The study documents how free trade agreements (FTAs) are being employed to pressure countries in the global South to adopt plant variety protection standards under the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention, the most stringent version of the international framework governing new plant varieties. The Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), established in Geneva, was originally designed to support industrial agriculture in Europe by granting monopoly rights over new crop varieties to private breeders for up to 25 years.

Under the UPOV 1991 model, farmers lose their traditional rights to freely save, exchange and reuse seeds, creating barriers to local seed sharing and biodiversity conservation. GRAIN’s analysis suggests that this shift has accelerated through bilateral and regional trade negotiations conducted outside the World Trade Organization (WTO), allowing stronger economies to advance corporate-friendly standards without international scrutiny.

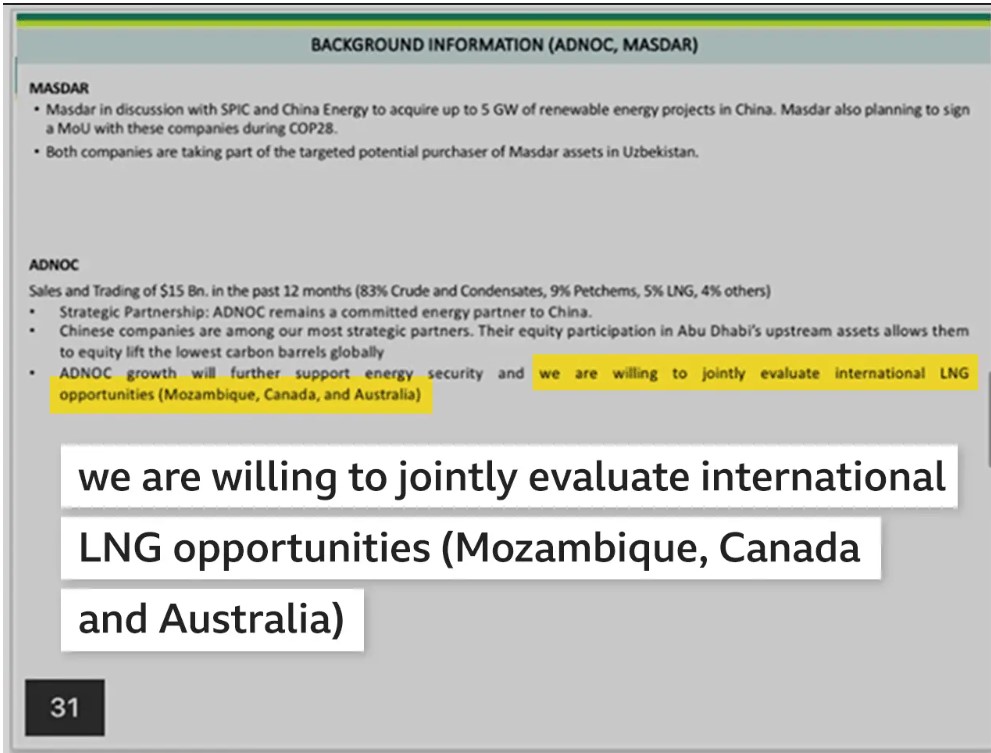

While the United States, European Union, Japan and Australia have long promoted such provisions, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has now emerged as a new and influential actor. According to the report, the UAE has successfully included UPOV-style clauses in its trade agreements with several Asian and African nations, including Cambodia, Malaysia and Mauritius. Its attempt to push similar standards on India, however, was resisted.

The report also highlights the UAE’s growing influence in global food systems, driven by extensive investments in agricultural land and food production across regions such as Africa, Latin America and South Asia. GRAIN argues that this expansion, coupled with the enforcement of restrictive seed laws, poses fresh challenges to food sovereignty and smallholder farmers’ autonomy.

Beyond UPOV membership, a number of trade deals have also required countries to introduce patent regimes for plants or to accede to the Budapest Treaty, which facilitates the patenting of micro-organisms. These obligations, the report notes, go beyond existing international norms and have often been implemented without public consultation or assessment of their social and ecological impact.

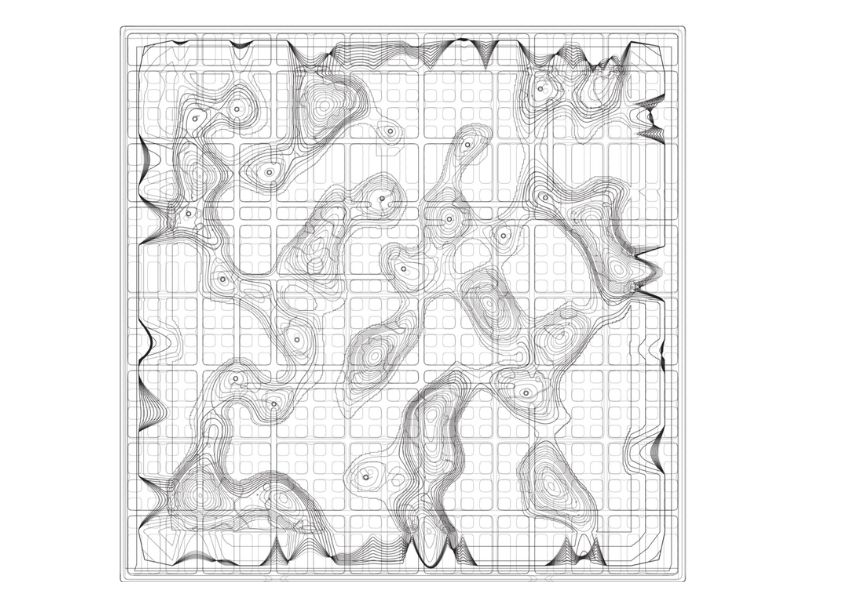

To illustrate the global reach of these agreements, Grain has released an interactive map tracking two decades of trade deals that incorporate UPOV-style clauses. The data reveal a consistent pattern of pressure on low- and middle-income countries to conform to stricter intellectual property regimes, effectively centralising control of seeds in the hands of multinational agribusinesses.

The findings have raised renewed concern among farmers’ groups and policy experts that global trade policy is being used as a tool to erode traditional agricultural systems, marginalise small producers and weaken national sovereignty over genetic resources. The report calls attention to the growing imbalance between the protection of corporate interests and the preservation of farmers’ customary rights in the global seed sector.