Women At The Wheel: How Affordable Machinery Can Make Women The Drivers Of India’s Agri-growth By 2030.

The feminisation of agriculture is no longer a passing trend; it’s a structural shift as according to the Agricultural Census, women formerly constituted nearly 73 percent of the pastoral agrarian pool

Byline: Yogesh Gawande, Founder, Niyo Farmtech

The face of Indian Agriculture is changing. Fields that were formerly cultivated and managed largely by men are now being decreasingly tended by women. With manly migration to metropolises accelerating and the youngish generation concluding out of husbandry, women form the backbone of pastoral husbandry. By 2047, close to 65 percent of India’s agrarian workers are anticipated to be women. Yet, the tools they work with remain largely designed for men. However, climate adaptability, and inclusive pastoral substance, If India is serious about achieving food security.

The Feminisation of Indian Agriculture:

The feminisation of agriculture is no longer a passing trend; it’s a structural shift. According to the Agricultural Census, women formerly constituted nearly 73 percent of the pastoral agrarian pool. They are not only planting, broadcasting, and harvesting, but also decreasingly taking on technical places similar to nursery operation, processing, and agri- entrepreneurship. The Economic Survey of 2017- 18 noted this growing feminisation, and more recent data confirm the line: the proportion of professed agrarian women workers rose from 48 percent in 2018- 19 to nearly 60 percent in 2022- 23. Still, this transition has come without acceptable tools or recognition. Only 14 percent of landholdings in India are in women’s names, which limits their access to credit, subventions, and decision- making power. Numerous women growers continue to work long hours with hand tools and outdated outfits, bearing the mass of donkeywork while lacking affordable mechanized support.

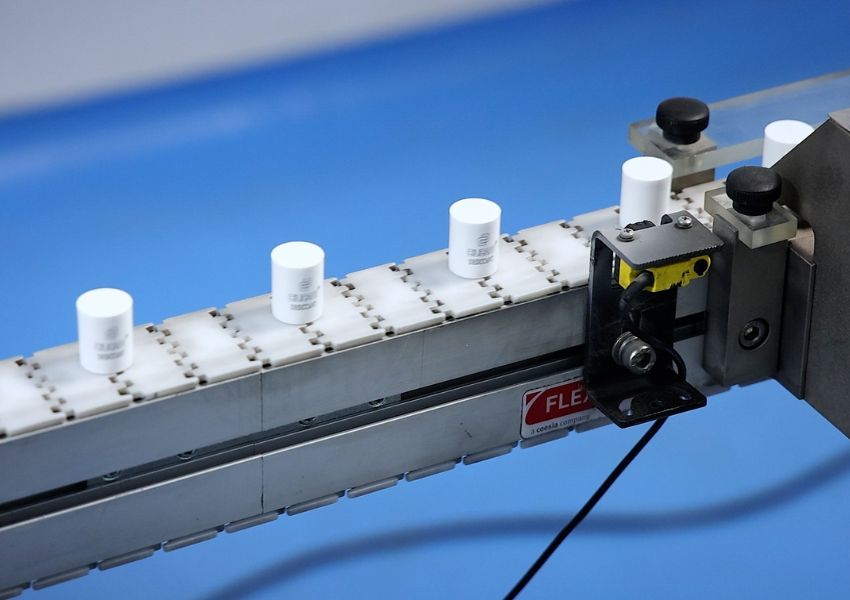

India’s Mechanisation Challenge:

At present, India’s farms are only 47 percent mechanized. Compare this with countries like the US or China, where robotization exceeds 90 percent. Our thing is to reach 75 percent robotization by 2047, but progress remains slow. Power consumption per hectare of cultivated land in India is just 2.54 kW, while the global standard is around 7.5 kW.

Mechanisation isn’t just about convenience — it transforms productivity. Studies show that it can save 15 to 20 percent of seeds and diseases, cut labour conditions by nearly 30 percent, reduce weeds by over to 40 percent, and increase yields by 13 to 23 percent. Beyond the ranch gate, post-harvest mechanisation in processing, storehouse, and value addition remains grossly underdeveloped. Without diving this, pastoral inflows won’t see meaningful growth. Ironically, while India lags in domestic mechanisation, we’re the world’s largest exporter of tractors. This incongruity underscores the fact that affordable, small- scale, and women- centric results haven’t entered the same policy or assiduity attention as large- scale ministry.

Why Women- Friendly Machines Matter:

Traditional ranch machines are heavy, energy- ferocious, and frequently ergonomically infelicitous for women. This isn’t just a matter of comfort — it is about access and commission. Affordable, featherlight, and easy- to- operate machines can help women growers save time, reduce physical strain, and ameliorate effectiveness. Also, women are proven to be more responsive to training and more disciplined borrowers than men. Studies show that women are 10 percent more likely to repay agrarian loans on time. They also tend to borrow stylish practices more unfeignedly during training sessions. By enabling women to use machines singly, we not only ameliorate productivity but also unleash a large, dependable client base for agritech companies and fiscal institutions.

Sustainability at the Core:

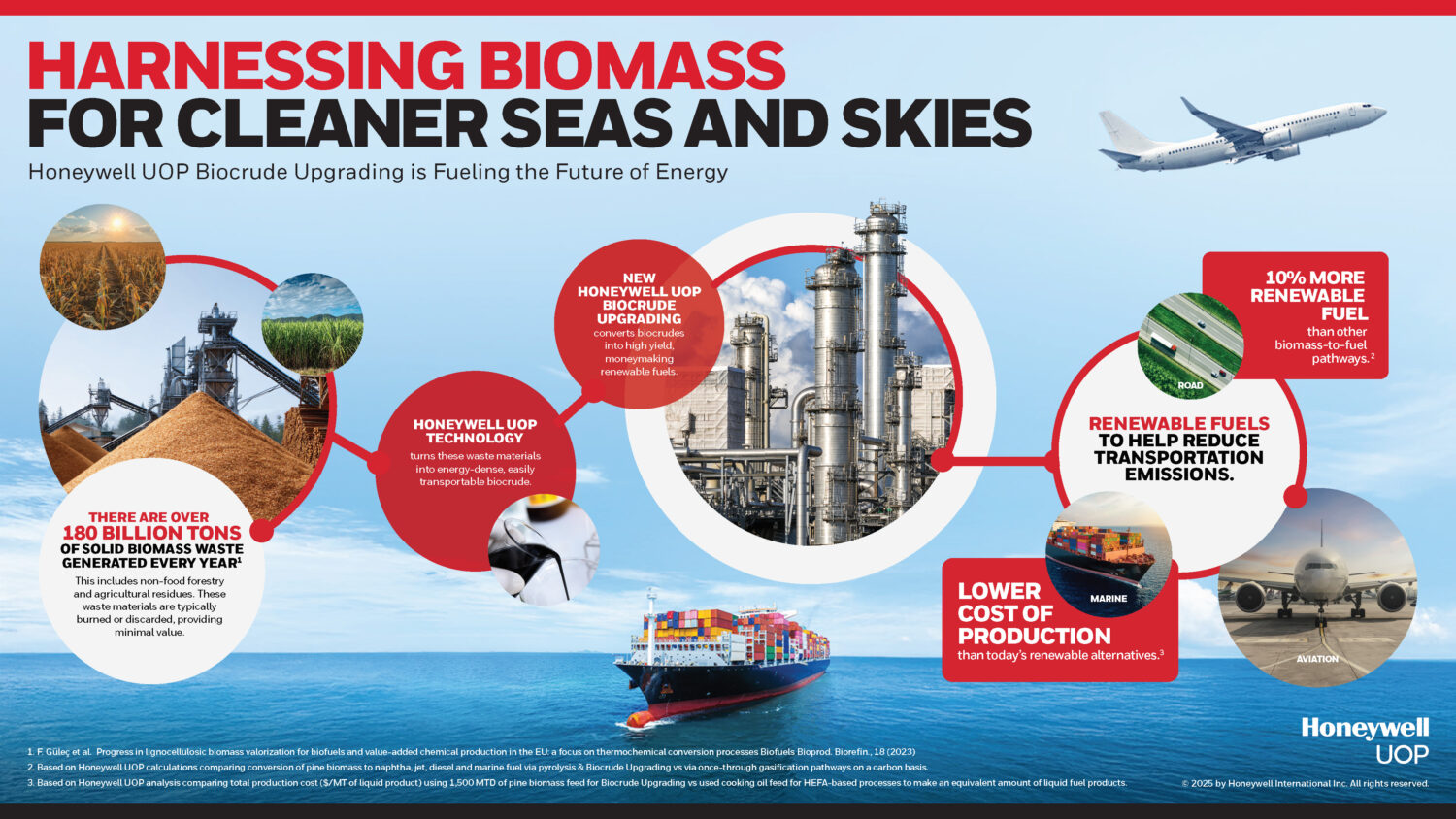

Farm ministry of the future can not be eyeless to the climate extremity. With husbandry both a victim and contributor to climate change, the coming surge of mechanisation must be sustainable. Electric tractors have formerly made their debut in India, and mongrel models, biofuels, and CNG- powered machines are on the horizon. Affordable, low-immigration outfit designed for small and borderline growers, the utmost of whom are women — can align India’s mechanisation drive with global climate pretensions. Mechanisation also plays a part in perfect husbandry, which reduces input destruction and greenhouse gas emigrations. Saving 20 percent of toxin, for example, isn’t just a profitable gain but an environmental imperative. Women- led mechanisation, supported by gender-sensitive engineering, could therefore come India’s unique donation to sustainable husbandry.

A few Case Studies from Maharashtra:

Encouraging exemplifications of women-friendly mechanisation and agritech relinquishment are formerly visible in Maharashtra. The Better Life Farming( Nav Tejaswini) programme, run in cooperation with the Maharashtra State Women’s Development Corporation, has empowered women to run Krishi Seva Kendras — original ranch service centres. These centres give access to inputs, mechanised services, and digital tools like the FarmRise app, which delivers real- time rainfall updates and requests advice. Since 2021, the programme has reached over 12,000 growers across 27 centres, proving that women- led agri- entrepreneurship can gauge when supported with technology. Also, in sugarcane husbandry, UPL’s programme has trained women to manage nurseries, a task taking high skill and perfection. This shift reduced seed costs by USD 54 per acre and bettered crop survival rates by 30 percent, directly boosting profitability. By designedly opting educated women for training, the programme has demonstrated how targeted interventions can change the economics of husbandry. These exemplifications punctuate the eventuality for affordable, gender-sensitive mechanisation to transfigure husbandry — not as charity, but as a smart business and development strategy.

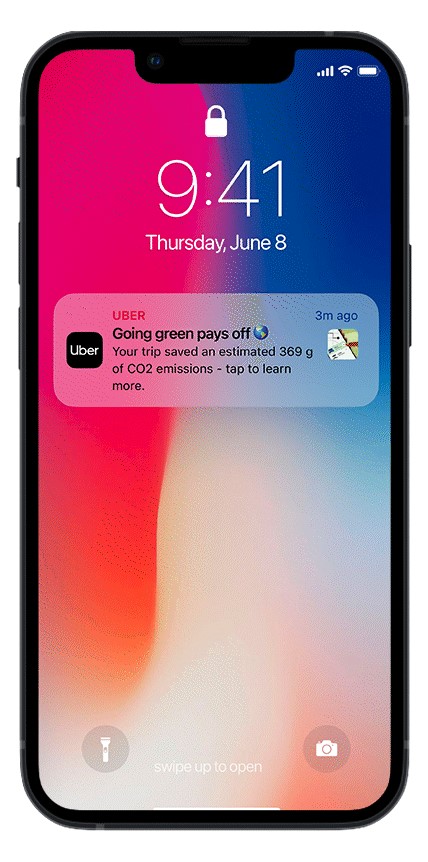

Digital Access and Fiscal Addition:

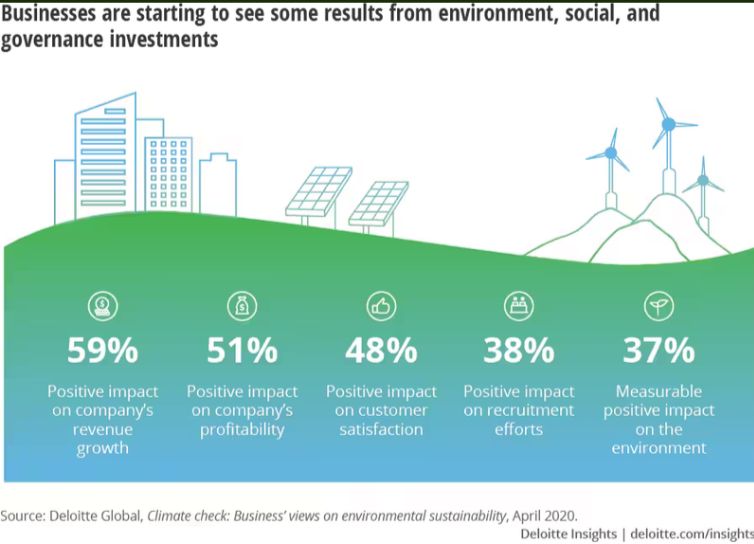

The rise in smartphone power among pastoral women is another game- changer. The gender gap in mobile internet use is shrinking, and platforms like WhatsApp and YouTube are formerly being used by women to learn new husbandry ways. This digital relinquishment lowers the cost of training and makes information dispersion briskly and more effective. fiscal addition has also shown what targeted support can achieve. Under the Jan Dhan Yojana, women regard holders have been shown to induce 12 percent more continuance profit for banks compared to men. However, crop insurance, and mechanisation loans the pastoral frugality could witness an important multiplier effect, If analogous strategies are applied to women growers — through acclimatized credit products.

Policy and Global Context:

India’s G20 presidency brought women-led development to the centre of global discussions, with commitments on gender equality, food security, and climate action. Institutions like ICAR have made decisive steps in developing technologies which are designed for women, from drudgery-reducing tools to collective farming models. But scaling these impactful projects requires sustained policy attention, better credit access, and public-private alliance .

Gender-sensitive research and innovation must counsel the next decade of agricultural transformation. As observed in Odisha, where women’s self-help groups were trained for fish farming and processing, inclusive programmes not only enhance incomes but also improve community nutrition. Such multi-layered outcomes—economic, social, and nutritional—should shape India’s agri-policy.

Barriers That Need Urgent Attention:

Challenges remain daunting. Women still earn 20 to 30 percent less than men for the same farm work. Health risks from pesticide exposure and heavy manual labour persist. Most of the time, training programmes are often inaccessible due to distance, timing, or cultural barriers. The most condemning part is, limited land ownership continues to deny women recognition as “farmers” in official records, locking them out of credit and government schemes. These impassable barriers must be dismantled through land reforms, gender-sensitive credit policies, engaging training modules, and a deliberate push for women-friendly machinery.

If India is to meet its agricultural goals by 2030, women must be at the centre of the strategies. Affordable, accessible agricultural equipment designed with women in mind can reduce drudgery, enhance productivity, and embed entrepreneurship. With supportive policies, digital access, and sustainable engineering, women can drive India’s next agri-growth story.

The feminisation of agriculture is already here. The question is whether we will help women to be sound with the tools they need to succeed—or continue to leave them struggling with hand tools in a mechanised world. By putting women at the wheel, India can build an agricultural future that is productive, inclusive, and sustainable.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication.